Introduction

Students arrive at school with distinct educational needs and personalities, as well as diverse life experiences, language, culture, hobbies, and learning mindsets. Skilled instructors know that all these elements have an impact on how children perform in school, and they vary their teaching to fulfill the needs of their learners. Educators in Canada are mandated to develop multilingual learning environments at school and in the classroom (Ragoonaden & Mueller, 2017). This responsibility is particularly crucial for teachers working in Canadian schools that comprise English as a second language (ESL) learners as the majority.

Precisely, Eastbrook Elementary School, under the Grasslands Public Schools division. The school is located in Brooks, Alberta, Canada, which is a rural territory in a small city of 10 000 people. The Elementary school consists of 485 students, of whom 96% use English as a second language. The most common languages are African ones, such as Somali and Oromo. The diversity of the learners in the school presents an excellent opportunity for assessing how educators can cater to the needs of ESL students.

Literature Review

Although the information on how ESL students employ assessment accommodations is limited, certain broad generalizations may be drawn. Primarily, instructors must be aware of their pupils’ capabilities in multicultural educational settings (Santos & Whiteside, 2015). This comprises awareness of their English proficiency, understanding of their mother tongue capabilities, particularly literacy competencies, and awareness of their topic area comprehension. When instructors identify areas of difficulty in their learners’ scores, they can attempt to correct them by modifying their lessons or giving assessment alternatives. According to Uccelli and Galloway (2017), there is one critical problem that instructors confront in education. In this regard, it determines which fundamental set of language abilities children understand or do not comprehend. The challenge of determining pupils’ past understanding and how to measure topic skills instead of English proficiency pervades many studies on dealing with ESL learners. Reading is among the most fundamental abilities and content categories taught in all Canadian schools. Enhanced vocabulary awareness and understanding, as literacy ability, assists learners in becoming more proficient readers.

Reading, writing, speaking and listening all fall under the umbrella of language areas, but they are grouped under the category of content areas to demonstrate their scholarly focus. The accuracy of an assessment is influenced by whether or not the modifications give an advantage to a certain group of pupils. ELSs must be permitted to utilize writing aids like spell-checkers and dictionaries throughout their writing assessments to represent better the actual academic contexts where these resources are commonly accessible (Oh, 2020). According to this research, learners with varying degrees of English language competence who had exposure to these tools nevertheless demonstrated their variations in levels while generating more precise writing with greater conviction. This implies that students’ skills were not unnaturally enhanced by merely offering additional resources.

Additional research has been done to examine this subject from the perspective of upper elementary and middle school learners. When Uccelli and Phillips Galloway (2017) assessed academic language using their appraisal system, they centered on learners’ perceptions of language. Teachers should evaluate how they may harness what abilities kids have, irrespective of whether they are competent in those capabilities or not, depending on their views and input from learners on how they see their ability with academic language (Uccelli & Phillips Galloway, 2017). Due to the widespread usage of reading and writing in the classroom for instruction and evaluation, students who master these literacy abilities will be better prepared for future coursework.

Among the most challenging aspects of dealing with ESL students in content, areas are recognizing that various learning forms are taking place simultaneously. However, certain individuals regard mathematics as a language-free discipline, neglecting the apparent linguistic obstacles. To be successful, ESL learners must master both arithmetic and English concurrently. According to Leith et al. (2016), this implies that an educator who has ESL pupils in their class is a language instructor and a math instructor.” Unfortunately, several subject-area instructors do not distinguish between language and subject expertise.

Vocabulary must be imparted and rehearsed regularly, emphasizing the terms learners may encounter in examinations. Essentially, math instructors must be mindful of ESL learners’ weaknesses and plan how to adjust their curriculum to engage them where they are and move them ahead−both linguistically and mathematically (Leith et al., 2016). This finding is consistent with Monarrez and Tschoshanov’s (2020) assertion that the knowledge presented in the mathematics curriculum should be transferred understandably to pupils. Given that student learning relies on instructors’ ability to communicate new ideas to ESL learners, instructors ought to be able to give information in many formats, including plain words.

Science confronts language and cultural obstacles in addition to content. Furthermore, Visuals, in drawings and infographics, must be included in assessments to assist learners (Hattan & Lupo, 2020). Conversely, adjustments in science might go further than direct language assistance and include alterations to the exam’s format. Educators and assessment creators should encourage students to utilize scientific inquiry while allowing for a wide range of responses. According to experts, formulated response questions assisted ESL students in showing their science expertise on science tests by enabling them to express their thoughts and explanations in their terminology (Turkan & Liu, 2012). Students may demonstrate their comprehension while accounting for minor syntactic or morphological flaws by permitting multiple forms of answers. Further, research has shown that instructors should guarantee that ESL learners have the opportunity to express what they are learning (Li & Peters, 2020). Educators must think about what is included in assessment language to ascertain that students understand how to perceive assessment criteria and task instructions.

English as a language has grown to be one of the most used languages worldwide as such, people with a different first language have enrolled in various classes to train to speak English. Governments and other organizations have established institutions where people with a different first language are trained to speak English fluently (Tsybaneva & Seredintseva, 2020). The aspect of teaching English is referred to as teaching English as a second language (TESL) or teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) (Junqueira & Kim, 2013). TEFL is applied in countries where English is not an official language, and TESL refers to teaching non-English speakers in English-speaking countries.

The methods of teaching and learning English vary based on the learners’ mastery and environment. Some only require little assistance because they have acquired some knowledge along the way, while others have never encountered English before. Such trainees will require more time and demotion to make any progress (ESL teacher Career Guide, 2020). The environment of the trainees has an impact on their learning process; the trainees who live among people who speak English are likely to learn the language faster and easier than those who live among non-speakers (Tsybaneva & Seredintseva, 2020). The difference can be attributed to the lack of people to train and practice with for those living among non-speakers.

Nevertheless, various models and theories have been developed to facilitate easy and effective English language learning. Educational materials like lecture recordings and speech assignments have been produced for the trainees and proven effective. There are, however, variants of English depending on geographical regions (Tsybaneva & Seredintseva, 2020). These differences occur in the pronunciation of words, but all the other aspects of the language are uniform worldwide.

ESL Needs Assessment

A needs assessment is the starting point toward determining a people’s demands. An ESL needs assessment is a valuable tool for determining the broad perspective of a group’s ESL education or training requirements (Cardozo-Gaibisso & Vazquez, 2020). It will assist an organization in selecting the most effective method to satisfy these demands. The essential element in evaluating whether or not to offer ESL programs is to conduct a needs assessment. It increases an organization’s chances of succeeding and helps it avoid wastage of resources. There are several advantages to completing a requirements assessment for learners. It defines needs and wants and gives information and remedies for classroom setup (Santos & Whiteside, 2015). This contributes to the end product’s relevance to the target population.

Perhaps a less considered benefit is that it enables an organization to raise people’s attention to ESL needs. The ESL Needs Assessment Tool was created with support from Alberta Employment, Immigration, and Industry (NorQuest, 2012). The objective of this tool is to give a framework for analyzing rural populations’ ESL requirements. Not only does the tool provide recommendations for evaluating needs associated with ESL teaching, but it likewise offers model instruments for completing the evaluation. Eastbrook Elementary may use this tool to help teachers throughout the assessment phase, from identifying needs to understanding and adopting the results.

There are patterns and standards that Eastbrook Elementary can utilize to accommodate the needs assessment tool for use in the school population. The administrators can use this tool to determine what language type and literacy coaching are required. Educators will be able to gauge to what extent their ESL students value their language and literacy development due to this questionnaire. After conducting an assessment of the school population, administrators may apply the results to decide what the institution should and might do to satisfy those needs (Alawdat, 2013). Appendix 1 shows a simplified Needs Assessment Tool that educators can use when determining the learning needs of ESL students.

Self-determination Theory (SDT)

Self-determination theory provides a foundation for studying individual motivation and personality. SDT establishes a model for conceptualizing motivational research, a formalized theory defining intrinsic and various extrinsic motivating factors and explaining the different functions of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in psychosocial development and personality traits (Deci & Ryan, 2012). According to the theory, individuals’ personal locus of causality (PLOC) varies widely. In the minds of some, their conduct is self-determined, and they are the ones who initiate and continue its meaning; it is internal. In the minds of others, outside forces determine the course of their life, forcing them to do particular acts; hence, this group will use an external PLOC (Deci & Ryan, 2012). Intrinsic motivation drives the internal locus, whereas extrinsic motivation drives the external locus.

Extrinsic motivation occurs when an individual is inspired by external variables like incentives, social acceptance, or avoidance of reprisal. This type of motivation directs human attention toward rewards instead of action. On the contrary, intrinsic motivation pertains to the drive to do something for the sake of enjoyment; it is thus a more powerful incentive than extrinsic drive. Three requirements result in intrinsic motivation. Firstly, being good at what one does; secondly, being attached to others; and thirdly, having independence.

Giving students the chance to acquire reflectance is critical for developing intrinsic motivation. Effectance is among the three points mentioned previously (being impeccable at their responsibilities), and it occurs when a student masters something they view as hard. According to Deci and Ryan (2013), effecting falls under the ‘Optimal zone of development’ as an activity that is considered sufficiently demanding to be complex yet within the learner’s competence. When instructors merely assign simple tasks to their learners, effectance does not develop. Deci and Ryan (2012) acknowledge that this is why the technique of easy accomplishments frequently flops with children who lack intrinsic motivation. Learners are not ignorant; they understand that the instructor is simplifying the task to make them look better and that the resulting accolades will have no effect on their self-esteem as topic learners. According to SDT, some people need to feel in control of their lives and accountable for their behaviors to find personal satisfaction and, as a result, motivation.

The Pedagogical Relevance of Self-Determination Theory

It could be beneficial for Eastbrook Elementary teachers to determine whether pupils in their classes have an internal or external PLOC. Assuming the intended student’s internal PLOC has been determined, it is critical to meet their self-determination necessities and provide them with a level of independence in and control over their learning (Deci & Ryan, 2012). For example, while organizing a reading lesson, conducting a presentation, or encouraging students to practice vocabulary available on the internet in a grade 2 class, the teacher should allow them to determine how they want the process to occur. This may be done while establishing specific criteria for consistency purposes. Persons with a high internal PLOC excel in self-directed classroom activities and settings (Beswick, 2017). Thus, Eastbrook Elementary instructors must maximize this character trait’s enhanced independence in second language acquisition. Learners with a high external PLOC will require additional encouragement, guidance, and a feeling of responsibility from instructors and guardians.

Practical Relevance of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Eastbrook Elementary instructors should strive to make classes as interesting as possible and to provide students with frequent opportunities to feel effective, as this can help to enhance their intrinsic motivation. Teachers may prepare each of their classes with a specific goal, for example, by asking how they can ensure that each child leaves the classroom feeling advanced (Ng & Ng, 2015). Additionally, instructors should encourage cohesiveness in the classroom by instilling a feeling of teamwork and a mindset that the entire class is collaborating toward a common objective and that each learner feels confident partnering with others (Ryan & Deci, 2020). For example, Somali or Oromo students can be grouped with non-ESL students to ensure that learners of the same ethnicity do not frequently partner with one another.

Students can additionally be provided with multiple opportunities for supportive peer input, such as urging all learners to appreciate the accomplishments of their peers. Eastbrook Elementary teachers must demonstrate to ESL students the advantages of learning the target language regarding future employment opportunities and self-development. Similarly, for each exercise that the instructor stages in classes in light of learning gains, they must utilize commendation to affirm the attempts of ESL learners. However, teachers must be careful not to over-praise; otherwise, the praise will lose its motivating value (Ryan & Deci, 2020). As previously said, some children can tell when a teacher is attempting to bribe them with flattery. This may lead to complacency and even a lack of drive in the long term.

The Needs Assessment Theory: Teacher Perspective

The needs assessment theory was developed specifically to assess the needs of trainees to ensure the efficiency of the training process. During the needs assessment, there are specific aspects that are evaluated to determine the process’s effectiveness: organization, person, and task. The organization aspect of analysis refers to the culture, goals, rules, regulations, and resources (Syakur et al., 2020). Culture refers to the values and beliefs of the trainees and those of the institutions that may hinder the training process.

For instance, different institutions uphold different values, and some of them may differ from those of the trainees as such training may be affected to some extent. The goals and ambitions of both the trainees and the organization must be parallel to ensure training occurs without any hindrances dues to differences in their ambitions (Long, 2019). The training process should adhere to the set legislation during execution. Implementing gender-neutral policies can avoid gender-based discrimination, which hampers efficiency during training (Syakur et al., 2020). Equality laws should also be applied to ensure all trainees are provided with equal opportunities irrespective of their differences (Junqueira & Kim, 2013). Time and capital are among the most valuable resources in the training process, without which training can barely continue. Therefore, through this analysis, the organization will be able to devise strategies to ensure these resources are available.

Task analysis is the second, and it involves analyzing the trainees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities. The analysis helps to establish where trainees need polishing and support and thus reduce margins of error among them (Long, 2019). Person analysis is the third and final aspect of needs analysis theory. It involves analyzing the different characteristics of the trainees (Syakur et al., 2020). The stage is crucial since all trainees have different behavior, attitudes, and skills. The trainer must capture the data correctly to design a suitable method of instruction for all the trainees.

Catering For the Needs of Diverse ESL Learners

Varying the Input and Output

Instructors can modify the input and output according to students’ performance and styles of learning while involving them in English learning exercises to improve their participation, passion, and, eventually, learning ability. Students in the same classroom must be given the same work. Varying the input implies providing students with similar instructional substance but delivering different assistance to enable them to accomplish the activity (Gass & Mackey, 2014). Activities may be used to provide help, although individual students may get various types or quantities of tasks.

Varying the output enables the students to choose how much of the assignment they want to complete. Providing easier or fewer activities to specific students is not limiting their ambitions (Jabbarpoor & Tajeddin, 2013). Instructors can, for example, provide a basic assignment to all students, supplemented by a variety of expanded tasks based on numerous intelligence. To capitalize on specific students’ abilities and fully enhance their potential, learners are allowed liberty in choosing expanded tasks.

Giving Questions Targeting Language and Cognitive Demands

Learners must be provided occasions to answer questions that are demanding but not beyond their comprehension to maintain motivation and attention in the learning process. Instructors may use queries that vary in terms of language and cognitive loads to adjust learners’ diverse English proficiency levels and mental function to meet the educational requirements of learners in higher grades, such as grade six (Walqui, 2012). These are questions that are used in everyday encounters with students to complete learning tasks, including those that are included in task forms at various learning levels. Eastbrook Elementary instructors can use the updated Bloom’s Taxonomy for creating questions with varying mental tasks. For instance, queries incorporating lower cognitive capabilities like retrieving plainly articulated information and advanced cognitive skills like finding links among diverse materials can be assigned for English assignments that demand a student to read texts and tackle an issue (Köksal & Ulum, 2018). Queries that demand higher-level reasoning skills, such as supporting a decision, on the other hand, maybe provided as an elective exercise to push students to accomplish deep comprehension and improve higher cognitive abilities.

Integrating Adaptive Grouping Techniques

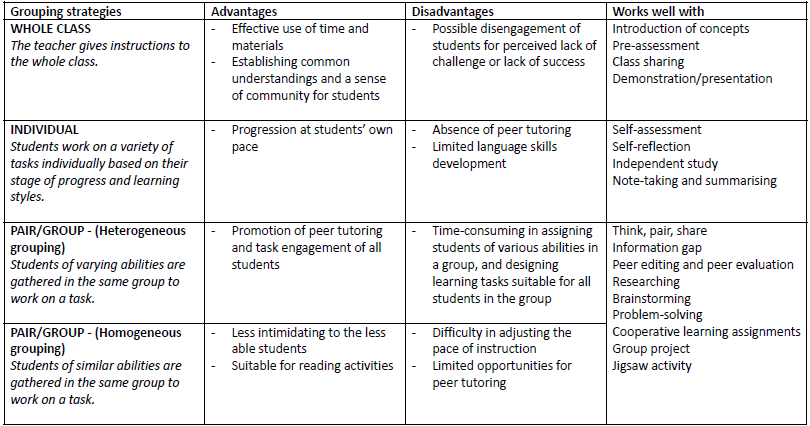

ESL students can learn quickly if they are grouped with other students with advanced or better communicative and language skills. Examples of grouping methods include entire class, group/pair, for example, homogenous and diverse, and individual or single grouping. Instructors are encouraged to explore learners’ interests as well as the type of exercise while using these approaches. When it comes to grouping, most students have their own choices. Individual task brings leads to more fulfillment for some people, whereas pairing or cooperative learning brings more enjoyment to others (Ma & Oxford, 2014). Educators may also choose group sizes depending on the structure of the task to achieve the learning objectives.

Case in point, bringing in novel ideas and closing the lesson in front of the entire class saves time and fosters a feeling of cooperation among students. Personalized exercises such as focused reading can cater to the needs of individual learners. Brainstorming and puzzle exercises, which are typically completed in pairs or groups, can improve collaborative learning and improve students’ commitment (Nasir & Aziz, 2020). Flexible grouping patterns, combined with carefully constructed tasks and assignments, can accommodate students of various learning styles and phases of advancement. Appendix 2 describes several grouping methods, their benefits and drawbacks, and the activities that can be used to support them.

Differentiating Instruction for ESL learners

There has been a lot of debate over what comprises suitable material, education, and evaluation for ESL learners, especially with the new focus on standards-based teaching. As instructors deal with the problem, it is now evident that educational equity can be reached if ESL students have access to the same challenging instructional coursework as native English speakers (Motha, 2014). As a concept, differentiated instruction is an instructional method that is meant to promote individual learners’ progress in a class of children with a range of backgrounds and capabilities (Borja et al., 2015). Differentiated teaching that takes into consideration ESL learners’ English language skills, and the numerous other variables that influence knowledge, is the ideal method to attain that objective. As a result, ESL students should benefit from the same broad concepts that pertain to tailored education for native English speakers.

Differentiated teaching aims to provide educational opportunities that account for variations in how people learn to guarantee that every learner has equal exposure to essential education and experience. Children who require more experience with crucial aspects before progressing may have their coursework adjusted (Watts‐Taffe et al., 2012). Therefore, differentiated instruction differs from customized instruction since each student does not acquire new concepts; rather, they all grasp the same thing in various approaches (Pham, 2012). Furthermore, each learner does not need to be coached independently; instead, differentiating teaching entails delivering the same work in various ways and at varying scales so that every learner can tackle it according to their preference.

Giving Prompt Feedback

Feedback is an important aspect of learning, irrespective of content area or competency level. Students of various stages of development and learning styles are assumed to obtain information and abilities at their own speed. As a result, continuous feedback, particularly written and verbal, must be provided depending on specific learners’ progress and development to assist them in setting their learning objectives and improving faster (Clark, 2012). Regular feedback can keep ESL learners on track as it helps them to monitor their progress.

The Reflective Practice Training Model

The training of ESL teachers has become progressive over the years; this has been enabled by the development of teacher training theories and models. These models are comprised of; the reflective model, the craft model, and the applied science model (Shameem, 2012). Each of these models has played a critical role in developing teacher training programs, and they still are. Despite the efficiency of these models, some are more effective than others, and a perfect example is a reflective model (Davies, 2012). The reflective practice developed was based on the works of various researchers and sociologists. These sociologists were Dewey, Donald A. Schon, and Michael Wallace.

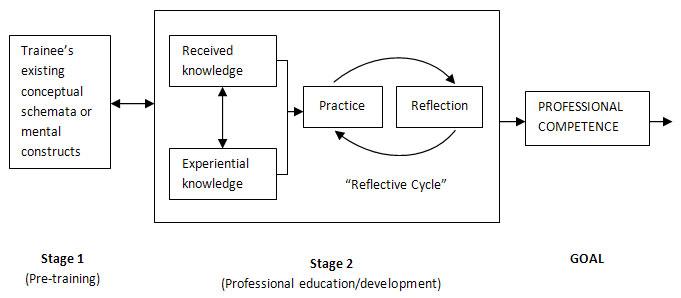

Dewey was the pioneer of the original reflective idea, and Wallace and Donald made additional explanations that made the theory effective. The theory assumes that teachers can only become competent in their profession if they reflect on their actions and practices (Davies, 2012). Through this, teachers can remember their own experiences as both teachers and students, enhancing their overall outcome. Wallace developed and incorporated two aspects of the model, which he believed teacher education could seldom do without (Shameem, 2012). These aspects were received knowledge and experiential knowledge; received knowledge refers to the concepts, skills, and theories that the student-teachers acquire during training.

On the other hand, experiential knowledge refers to the knowledge and skills that the teachers acquire during their practice and experience. The model has three knowledge levels: pre-training, professional development, and professional competence. The first level is pre-training; this refers to the prior knowledge about the training process that the trainees are believed to possess (Davies, 2012). The second level of knowledge is professional development; here, the trainee is instilled with professional knowledge through practice and theoretical information. The third and last level is the professional competence level.

At this level, trainees are exposed to immense knowledge to enhance their mastery and competency (Davies, 2012). The model assumes a cyclic design through which the trainee is trained to achieve the set objectives (Shameem, 2012). The cycle aims at ensuring an ongoing development process for the trainees. The model is designed to prepare the trainee for the various levels of knowledge among the students in the English program (Davies, 2012). Therefore, when the teacher enters class and analyses each of their student’s knowledge level, they will be able to adjust the methods of instruction accordingly to accommodate the needs of all the learners.

Through the analysis, teachers can recall their previous experiences as teachers or students. Thus they apply the skills they acquired during their practice or observed from their superiors (Davies, 2012). As teachers, the trainees are bound to make decisions in class for the class; therefore, they must be careful in analyzing the impacts of their decisions on their learners (Shameem, 2012). The trainees can also evaluate the efficiency of their techniques and instruction methods by analyzing their students’ activities. By analyzing these activities, the teachers will know the effectiveness of their performance.

In addition, by analyzing the activities of their learners, the teachers will be able to know the strengths and shortcomings of their methods of instruction. Thus they will be able to make the required corrections and solve the problem permanently in the future.

Some of the advantages of using this model are; that trainees are treated as co-participants and not passive participants. During training, the trainees are actively involved in the learning process, enhancing their understanding and comprehension (Shameem, 2012). In trainee-centered training, during training, the methods of instruction used are designed to suit the trainees’ needs and accommodate all their differences.

The training exercise is planned so that the trainees are exposed to vast knowledge to make them resourceful and conversant. The training process also equips the trainees with decision-making (Davies, 2012). These skills are essential in the teaching profession because teachers have to make daily decisions (Shameem, 2012). The decisions must be informed and based on facts to guarantee the expected outcomes. Unlike most other models, the reflective practice provides trainees with the most relevant factors that ensure complete teacher development.

Nevertheless, this model has its limitations too, and they consist of the experiences of each trainee being on an individual level, none of them are shared (Shameem, 2012). The model promotes ignorance at the expense of professional progress, and this is because it is not flexible; thus, participants tend to shut out the outside world (Shameem, 2012). The model lacks adequate structures that articulate the complete reflection of trainees.

Conclusion

ESL programs highlight the vast multiculturalism that characterizes Canadian schools in the twenty-first century. In today’s classrooms, learners come from a wide range of educational backgrounds, different cultures, styles of learning, and dialects. As demonstrated in this report, a needs assessment assists a teacher in planning learning content in a multicultural setting such as Eastbrook Elementary. Since language education is variable, instructors must determine where learners are underperforming. Moreover, an effective teacher needs to ensure learners understand only what is relevant. This implies that a student who wants to study English for commerce will have very diverse demands than a middle school adolescent who wants to enhance their communicative abilities. ESL students may concentrate on what function English will have in their prospective professional and personal ambitions by responding to questions regarding their motivations and ambitions.

References

Alawdat, M. (2013). Using e-portfolios and ESL learners. Online Submission, 3(5), 339-351. Web.

Beswick, D. (2017). Cognitive motivation: From curiosity to identity, purpose and meaning. Cambridge University Press.

Borja, L. A., Soto, S. T., & Sanchez, T. X. (2015). Differentiating instruction for EFL learners. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5(8), 30-36. Web.

Cardozo-Gaibisso, L., & Vazquez, D. M. (2020). Handbook of research on advancing language equity practices with immigrant communities. Hershey, PA: IGI Global,

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 205–249. Web.

Davies, S. (2012). Embracing reflective practice. Education for Primary Care, 23(1), 9-12. Web.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416–436). Sage Publications Ltd. Web.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

ESL teacher Career Guide. Teacher Certification Degrees. (2022). Web.

Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A. (2014). Input, interaction, and output in second language acquisition. In B. Vanpatten, & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 175-200). London: LEA.

Hattan, C., & Lupo, S. M. (2020). Rethinking the role of knowledge in the literacy classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S283-S298. Web.

Jabbarpoor, S., & Tajeddin, Z. (2013). Enhanced input, individual output, and collaborative output: Effects on the acquisition of the English subjunctive mood. Revista signos, 46(82), 213-235. Web.

Junqueira, L., & Kim, Y. (2013). Exploring the relationship between training, beliefs, and teachers’ corrective feedback practices: A case study of a novice and an experienced ESL teacher. Canadian Modern Language Review, 69(2), 181-206.

Köksal, D., & Ulum, Ö. G. (2018). Language assessment through Bloom’s Taxonomy. Journal of language and linguistic studies, 14(2), 76-88. Web.

Leith, C., Rose, E., & King, T. (2016). Teaching mathematics and language to English learners. The Mathematics Teacher, 109(9), 670-678. Web.

Li, N., & Peters, A. W. (2020). Preparing K-12 teachers for ELLs: Improving teachers’ L2 knowledge and strategies through innovative professional development. Urban Education, 55(10), 1489–1506. Web.

Long, M. H. (2019). The second language needs analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ma, R., & Oxford, R. L. (2014). A diary study focusing on listening and speaking: The evolving interaction of learning styles and learning strategies in a motivated, advanced ESL learner. System, 43, 101-113. Web.

Monarrez, A., & Tchoshanov, M. (2020). Unpacking teacher challenges in understanding and implementing cognitively demanding tasks in secondary school mathematics classrooms. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 1–17. Web.

Motha, S. (2014). Race, empire, and English language teaching: Creating responsible and ethical anti-racist practice. Teachers College Press.

Nasir, N. A. M.., & Aziz, A. A. (2020). Implementing Student-Centered Collaborative Learning when Teaching Productive Skills in An ESL Primary Classroom. International Journal of Publication and Social Studies, 5(1), 44–54. Web.

Ng, C. F., & Ng, P. K. (2015). A review of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of ESL learners. International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, 1(2), 98-105. Web.

NorQuest. (2012). English as a second language – ESL Intensive Benchmarks 3-7. NorQuest College. Web.

Pham, H. L. (2012). Differentiated instruction and the need to integrate teaching and practice. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 9(1), 13-20. Web.

Ragoonaden, K., & Mueller, L. (2017). Culturally responsive pedagogy: Indigenizing curriculum. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 47(2), 22-46. Web.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, Article 101860. Web.

Santos, M. G., & Whiteside, A., (2015). Low-educated second language and literacy acquisition. In Low Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition: Proceedings of the 9th symposium. Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Publishing Services.

Shameem, T. (2012). The models of teacher education. The Models of Teacher Education. Web.

Syakur, A., Zainuddin, H. M., & Hasan, M. A. (2020). Needs analysis of English for specific purposes (esp) for vocational pharmacy students. Budapest International Research and Critics in Linguistics and Education (BirLE) Journal, 3(2), 724-733.

Tsybaneva, V. A., & Seredintseva, A. S. (2020). Features of the development of an additional professional program for teachers of English, taking into account their professional needs. Siberian Pedagogical Journal, (2), 73-82. Web.

Uccelli, P., & Phillips Galloway, E. (2017). Academic language across content areas: Lessons from an innovative assessment and from students’ reflections about language. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(4), 395-404. Web.

Walqui, A. (2012). Instruction for Diverse Groups of English Language Learners. WestEd. Web.

Watts‐Taffe, S., Laster, B. P., Broach, L., Marinak, B., McDonald Connor, C., & Walker‐Dalhouse, D. (2012). Differentiated instruction: Making informed teacher decisions. The Reading Teacher, 66(4), 303-314. Web.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2