Introduction

This chapter contains an overview of what other scholars have written about the importance of including the views of international students in higher education leadership. The focus of the investigation is on leadership practices in the higher education sector with the attention centred on explaining the importance of diversity. These core areas of research are instrumental in understanding how students’ views could help to improve higher education leadership practices in higher education.

Importance of Diversity in Leadership

Diversity is an important trait in leadership that encompasses the inclusion of people with different demographics, including their race, sexual orientation, class, religious affiliation, and gender, just to mention a few (Winther, 2018). The importance of diversity in leadership has been affirmed through research investigations that have highlighted its importance in team management (Leroy et al., 2021). Some of these studies have also investigated diversity from a cultural lens and advance the view that assembling team members from different cultural backgrounds helps to improve performance (Raithel, van Knippenberg and Stam, 2021). However, there are challenges associated with embracing diversity in the team setting.

In a study to understand the moderating effects of a leader’s cultural background and their tenure in positions of power revealed that their experience with diversity helped to moderate their effectiveness in leadership (Raithel, van Knippenberg and Stam, 2021). For example, a leader’s experience with the host culture helps to influence the kind of relationship they would have with the team members and the tenure of their position at the helm of the leadership structure (Raithel, van Knippenberg and Stam, 2021). Nonetheless, the effects of a person’s culture on their tenure in leadership was strongest when he/she has a short stint at leadership (Raithel, van Knippenberg and Stam, 2021). In this analysis, it is believed that negative stereotypes are likely to reduce the effectiveness of leadership, especially based on perceived differences between minorities and the dominant culture.

Creativity in Leadership

The principle of imaginative education has been largely used in explaining creativity in leadership practices within the organizational setting. It is an educational theory that looks at creativity like soil that breeds ideas on effective leadership management practices in most community settings. Education and cognitive tools have been highlighted as tools to promote imagination in the education context and leadership is central to understanding how it works (Judson, 2021). In investigations conducted by Judson (2021) and Ogbeibu et al. (2020), leaders were encouraged to use education as imaginative tools for promoting creativity in the organizational context. Relative to this assertion, future leadership practices are seen to take the shape of creative approaches to organisational development as highlighted by Judson (2021). This analysis tries to define power arrangements between leaders and students by using imagination to define the relationship between both parties.

The concept of imaginative leadership is increasingly moving away from ideologies centred on highlighting unique qualities of specific groups of people to another that promotes transformational success by working with other people or stakeholders. Cognitive tools, such as storytelling, have been highlighted as useful tools for developing empathy in leadership (Judson, 2021). In this context of analysis, creativity in leadership is seen as an effective tool for developing leadership skills in management by merging individual and collective imaginative elements to form a cohesive understanding of leadership practices (Judson, 2021). Relative to this assertion, participatory forms of leadership have been highlighted as useful tools for fostering creativity in the higher education leadership sector. However, organizations are cautioned from adopting undemocratic forms of participatory leadership because they could foster exclusion (Joslyn, 2018; Judson, 2021). Particularly, Joslyn (2018) supports this statement by saying that the undemocratic system could lead to incidences of cultural cloning, which could normalize the exclusion of ethnic minorities from leadership structures.

Creativity in leadership is essential in coming up with solutions for problems affecting an organization or institution (Thompson, 2018; Zheng et al., 2020). He, von Krogh and Sirén (2021) address the same issue by linking the process of knowledge creation to creativity. They also say that experts may be drawn from different fields to develop creative solutions to contemporary problems (He, von Krogh and Sirén, 2021). The authors also caution that expert advice may hinder creativity through limited knowledge creation processes (He, von Krogh and Sirén, 2021). These views were developed after assessing the role of leadership in promoting knowledge creation objectives within an environment characterised by task uncertainty and informal communication channels in leadership (He, von Krogh and Sirén, 2021). The authors also found out that task uncertainty improves the quality of creativity and moderates the effect that expertise involvement would have on team leadership (He, von Krogh and Sirén, 2021). This type of relationship was strongest in institutions that were task-oriented as opposed to relationship-oriented.

In another investigation, Leroy et al. (2021) explored the role of leadership in developing team creativity. The researchers conducted this analysis by evaluating their role in fostering creativity by encouraging members to understand their team experiences (Leroy et al., 2021). It is believed that in this type of setting, team creativity is best fostered when members derive their uniqueness from within the team itself (Leroy et al., 2021). This aspect of analysis is associated with the concept of team-derived inclusion (Higdon, 2016; Matthews, 2018; Liang, Dai and Matthews, 2020). Researchers have also pointed out that all members of a team should be encouraged to express their views freely because they are part of the main team membership structure (Khan et al., 2020; Tillmann et al., 2020; Nyberg, Backman and Larsson, 2020; Eshghinejad and Moini, 2016; Jabbar et al., 2020). Similarly, they are encouraged to openly express their unique viewpoints and defend them, if there is need to do so (Khan et al., 2020). This analysis was done by evaluating the role of leadership in fostering creativity within teams in an organizational setting.

Similarly, in an organizational context, Bjørkelo et al. (2021) ‘did a similar study to understand how organizations retain employees from diverse backgrounds in the public service sector. The researchers say that much of the evidence on diversity management in an organization setting stems from the concept of representative bureaucracy (Bjørkelo et al., 2021). It suggests that organizations should have their employee makeup mirror that of the society from which it comes from (Bjørkelo et al., 2021). These recommendations were developed after reviewing data from official statistics and interviews from notable personalities who were conversant with the concept of diversity in management (Bjørkelo et al., 2021). These sources of data advocate for the need for organizations to train their employees on the need to embrace diversity in the workplace.

The role of leadership in fostering creativity within the organisation is also supported by studies, which show its importance in developing students’ talents. For example, Cheung, Hui, and Cheung (2020) link leadership and creativity to the emergence of a new crop of gifted students within the several educational levels. The emergence of this group of students was also associated with the need for educationists to understand diverse educational and affective needs (Cheung, 2020). The recognition of these needs has also been linked to the development of diversity within the school setting (Bjørkelo et al., 2021). It has also been related to positive educational outcomes including curriculum development, student development and parents’ empowerment (Cheung, 2020). Overall, they suggest the existence of a link between creativity and leadership

Diversity in the Educational Setting

For a long time, student voice has been neglected in higher education decision-making. Particularly, western universities, have paid little attention to the voice of international students in policymaking (Javaid, Söilen and Le, 2020; Bislev, 2017). Insights drawn from the sampled articles suggest that the education sector lags behind others in embracing diversity in leadership. Thomson and Davignon (2017) hold this view by saying that despite the potential that diversity holds in improving institutional practices it remains an aspirational quality for most organisations, in terms of policy and practice.

The current evidence suggests that most of the gains made in promoting diversity in the higher education field have been centred on promoting gender equality (Worsham et al., 2021). For example, a study authored by Aiston and Yang (2017), which was based in Hong Kong, showed similarities in underrepresentation of women in Hong Kong and western societies. Nonetheless, the researchers acknowledge that there is insufficient data regarding the representation of women in the education sector (Aiston and Yang, 2017). This problem breeds new ones that stem from a lack of transparency in leadership practices and the failure to monitor or track the progress made in education institutions, regarding the diversity of employees and teachers.

Despite the pieces of evidence espoused by researchers above, the representation of African-American and minority groups in leadership has been the most discussed problem for most institutions of higher education (Aiston and Yang, 2017).. This is also true for Asians and minority ethnic groups in the UK. An English-based study authored by Fernando (2020) shows the scope of this problem by suggesting that it is notably prevalent in senior positions of England’s higher education sector. A study by Arday (2018) also highlighted the importance of diversity in leadership by mentioning the underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in leadership. Specifically, the researchers made note of the exclusion of ethnic minorities in educational leadership circles among egalitarian nations (Aiston and Yang, 2017). These countries are often associated with equality and diversity but strict rules on educational leadership make it difficult to exercise these qualities in the higher education setting (Arday, 2018). Authors have also pointed out that the UK higher education system is insensitive to the needs of diverse populations that ought to be represented in the higher echelons of leadership (Arday, 2018). When using race as the primary object of analysis, the quest by some leaders to advance their careers prevents most of them from achieving the true diversity goals in leadership.

Apart from race, diversity has also been explored from the perspective of people’s sexual orientation. Lee (2020) conducted such a study by investigating difficulties that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) teachers experience when trying to ascend to leadership positions. The author suggest that to solve some of the social barriers affecting the involvement of these minorities in leadership positions, actions should be focused on subscribing to the values of authentic leadership which celebrate inclusion and diversity (Lee, 2020). The same values also encourage education institutions to accept differences among students and teachers as well as challenging existing dogma on leadership to create opportunities for improvement. In this regard, it is recommended that teachers receive training and mentoring about diversity to incorporate them in leadership positions (Lee, 2020). These measures have been proposed to understand how courageous leaders can inspire teachers and students to take the mantle of leadership.

American-based studies have investigated the same issue of diversity in the education sector by focusing on adult learners as another group of students whose views have been ignored in the broader context of education leadership. This statement is highlighted by Chen (2017), who says that college education is traditionally youth-centred but the number of people who live on campus and live a traditional student life only forms a small percentage of students seeking post-secondary education. In this regard, adult learners are perceived to be a disadvantaged part of the student population because work stresses do not allow them to fully participate in mainstream educational activities (Chen, 2017). Therefore, the youth-centred nature of education leadership is regarded as a significant barrier to the involvement of adult learners in the running of school activities.

The above pieces of evidence suggest that discussions about diversity are not only limited to the organizational setting. Indeed, some researchers have also evaluated the role of diverse leadership structures in public sector management or in government circles (Hansen and Clark, 2020). The researchers say that traditionally underrepresented communities in leadership such as African-Americans and Latinos have become increasingly involved in education leadership (Hansen and Clark, 2020). The process has been hailed as being beneficial to the political maturity of societies through representative political representation.

Challenges of Underrepresentation

Research shows that some of the problems of underrepresentation of minority groups stems from the number of leadership positions available and the methodologies selected by an institution or organisation to identify their leaders (Hansen and Clark, 2020). Relative to this assertion, it is reported that organizations, which have many representative positions in their leadership structures, tend to have more minorities and women represented in their overall structures (Hansen and Clark, 2020). Similarly, those that have few such positions tend to be patriarchal as the dominant leaders jostle for power, devoid of the need to be representative of their communities.

The struggles expressed by Chinese students towards reaching high levels of educational leadership have been traced to several factors affecting people’s perceptions of ethnic minorities (Mullen, 2017). Particularly, Palaiologou and Male (2019) draw our attention to the role that early childhood plays in creating an environment of prejudice and disposition of ethnic minorities. They posit that this type of education helps to create prejudices and bias among students and teachers regarding ethnic minorities. Therefore, researchers say that the exclusion of ethnic minorities from leadership stems from the history of societies, their surrounding cultures, and subjective perspectives about racial struggles that influence how well an organization understands the importance of embracing diversity (Yu, 2021).

Market-related challenges have also been identified to influence diversity development in the educational setting. In line with these observations, researchers have recommended that students be taught about the importance of diversity and social inclusion in their educational curriculum (Grier, 2020). The goal is to build awareness among them, such that they do not pose a barrier to the development of new ideas for fostering inclusivity in leadership. This problem is also present in specialized schools that teach children with disability (Cooc and Yang, 2016). Evidence shows that racial disparities are also witnessed when analysing the qualification of teachers in these schools with educators from minority groups having the least qualifications compared to their counterparts from majority ethnic groups (Cooc and Yang, 2016; Raaper, 2021; Lyons, Brasof and Baron, 2020). Relative to this assertion, Janssens and Zanoni (2021) say that to address the problem of diversity in leadership, it is important for leaders to move beyond the ideation of diversity as a concept and refrain from relying on empirical pieces of evidence that have traditionally limited people’s understanding of diversity and its role in promoting social change. In this regard, the concept of diversity should not be regarded as an emerging concept but rather one that has reached maturity.

Summary

The existing literature supports the view that student voice is integral in improving the quality of leadership in higher education. However, most of the evidence gathered in this chapter seem to focus on several groups of minorities, such as women and disabled people, while ignoring the plight of international students and the unwillingness of school administrators to accommodate their views at a policy level.

Methodology

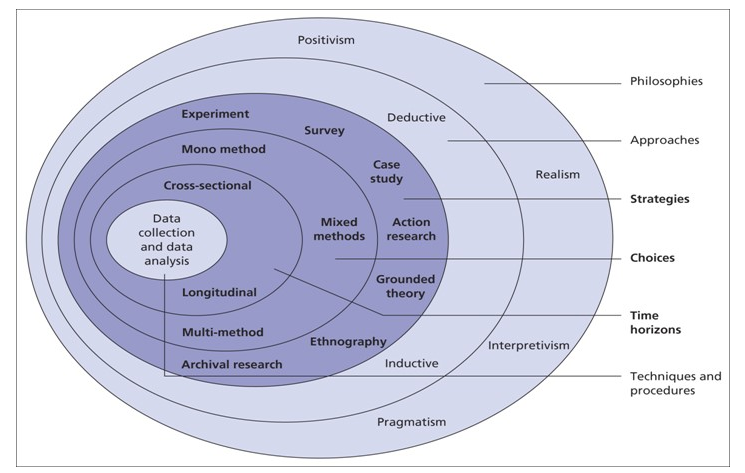

This chapter describes techniques used by the researcher to meet the objectives of the study. The structure of this chapter is borrowed from the works of Melnikovas (2018), which explain processes associated with developing academic studies. The author says that research studies are conducted in five phases, including philosophy, approach, strategies, choices, and time horizons (Melnikovas, 2018), as described in figure 3.1 below.

The researcher used the items described above to inform the format of this chapter as outlined below.

Research Philosophy

A research philosophy helps to explain the belief a researcher has in conducting a study. Relative to this statement, researchers use four main philosophies to conduct their studies: interpretivism, positivism, pragmatism, and realism (Woodley and Smith, 2020). The positivism philosophy argues that research issues can be explained objectively by focusing on one subject at a time. Comparatively, the interpretivism school of thought advocates for the view that a research issue can be explained by factors that are out of the control of the human mind (Melnikovas, 2018). Therefore, it emphasizes the need to view research problems through people’s individualistic or collective experiences. In this setup, the role of the researcher in evaluating the social world is highlighted.

Alternatively, the pragmatism research philosophy advocates for the use of research techniques that would best answer the problem under investigation (Melnikovas, 2018). Stated differently, the process of selecting research tools depends on the environmental context of analysis. Based on the suitability of each of the research philosophies highlighted, the interpretivism framework emerged as the best fit for the present investigation. Its selection is informed by the subjective nature of leadership and the complexity of understanding sociocultural issues about international students’ experiences highlighted by the research respondents in assessing leadership qualities.

Research Approach

The research approach used in an academic investigation influences the format of reasoning or sequence of processes involved in developing research findings. Two main research approaches are used in academic studies – inductive and deductive reasoning (Hatta et al., 2020). The deductive model relies on broad generalizations of pieces of evidence to create one cohesive narrative that helps to explain a research issue. Comparatively, the inductive research model relies on one piece of evidence to make generalizations about various aspects of a research issue. Given that the present study uses the views of a few people to understand the importance of integrating the voices of international students in higher education, the inductive research approach emerges as the best fit for the investigation. It facilitates the use of views from one group of international students to generalize leadership qualities in the broader UK higher education setting.

Research Strategy

The techniques adopted by a researcher to answer study questions depend on the strategies adopted. As highlighted by Melnikovas (2018) in figure 3.1 above, researchers have an option of choosing from seven strategies, including surveys, experiments, case studies, action research, grounded theory, ethnography, and archival research, when designing their studies. The case study approach was used in the current investigation because evidence was gathered from a group of international students in a UK university to make inferences about leadership qualities in the higher education sector.

As will be highlighted in subsequent sections of this paper, the case study will involve Chinese students studying in the UK. This research strategy was selected for the current investigation because international students in the UK form a small percentage of the student population and their views could be sampled using the case study research approach. In context of analysis, Study in UK (2021) says that about 485,645 out of 2,383, 970 students enrolled in the UK higher education sector are international students. Comparatively, Chinese students account for about 120,385 of the total number of international students studying in the UK higher education sector (Study in UK, 2021). This number represents the greatest percentage of non-EU students studying in the UK.

The case study approach was instrumental in getting in-depth views of a sample of the Chinese international students studying in UK institutions of higher education. The justification for its use in the present investigation was also influenced by the understanding that diversity in leadership requires a careful understanding of the depth and experiences of international students, which was best captured using the case study approach (Melnikovas, 2018). Additionally, researchers hail the use of case studies in such research contexts because it allows them to capture a range of perspectives about specific research phenomena, some of which cannot be easily obtained using a survey or similar research strategies (Melnikovas, 2018).

Research Choice

The qualitative research approach was the main research choice for the present investigation. It is primarily preoccupied with the use of non-statistical tools of data collection and analysis to answer a research question (Hesse et al., 2019). Its relevance to the current topic was influenced by the subjective nature of the two main research variables in the study: student voice and leadership. In other words, the qualitative research choice gave the researcher an opportunity to understand the subjective contexts of the respondents’ views regarding the research topic. In this regard, it was possible to understand their attributes and views about leadership by assessing subjective variables affecting leadership, including attitudes, culture, norms, and values that may be held by international students and enrich leadership practices in the broader context of higher education governance (Hesse et al., 2019).

Time Horizon

Research variables can be assessed using either cross-sectional or longitudinal methods. Cross-sectional research is often used in situations where variables are analyzed for a specific period, while the longitudinal technique is applied when there is an intention to measure variables over a long time (Banning et al., 2020). Based on these differences, the cross-sectional time horizon was used for the present study because the research phenomenon was investigated at one point in time (Saito and Liu, 2021). Therefore, the longitudinal research design was not applicable in the current investigation because the researcher sampled the respondents’ views in one session.

Data Collection

The present study will include data from two sources: interviews and secondary research. Interviews provided the main source of data, while the information collected from secondary research was used to complement the primary data. Researchers have mainly used the interview technique to understand the views of researchers regarding various subjects or issues in research (Blake et al., 2021; Irvine, 2011). Therefore, by sampling the views of a small number of people, the researcher effectively obtained different types of data relating to the views of international students regarding leadership in the higher education field, including the attributes, behaviors, feelings, preferences, opinions, and knowledge about diversity that would enhance the quality of leadership in the higher education sector. Therefore, primary data from interviews provided the foundation for the development of the present findings.

The interview questions were open-ended and tailored towards obtaining in-depth information relating to leadership practices in the higher education setting (see appendix 1). Different aspects of leadership were included in the probe, including discussions on problem solving, development of policy-making decisions, power-balance between students and administrators, and creativity in leadership. These aspects of leadership behavior are highlighted in research studies, such as Kim, Baik and Kim (2019) because of their importance in maintaining effective leadership practices in the education sector. Notably, in the higher education field, researchers such as Winther (2018), Thao and Kang (2018) have mentioned the same leadership qualities in developing effective policies on governance.

Focus group discussions were available as an alternative method of collecting primary data, but it was difficult to get all respondents at one meeting place due to logistical and scheduling reasons. The interviews were conducted in-person at the school cafeteria in compliance with UK government guidelines on COVID-19 infection control measures (see appendix 3). These guidelines are in relation to social distancing as well as taking all reasonable precautions, in terms of limiting the spread of the virus by maintaining a 1.5-meter social distance between the interviewer and interviewee as well as wearing masks during the interview (Davis et al., 2021).

As mentioned above, secondary data provided auxiliary information relating to the respondents’ views on leadership in the higher education sector. The main sources of secondary information were books, journals, and reputable websites. This type of information was included in the investigation to maintain the reliability and credibility of data used in the research. Secondary data was sourced online through reputable databases, including Sage Journals, Springer Link, Google Books, and Emerald. The pieces of information sourced from these databases were instrumental in contextualizing student voice within the wider realm of education leadership. They were further examined to understand its correlation with leadership practices in the higher education sector.

Research Participants and Sampling Method

Before taking part in the study, the participants were informed of the objectives and nature of the current investigation in an introductory letter mailed to them (see appendix 4). This letter detailed the purpose of the study, its risks, and techniques. After following these steps, the researcher interviewed 12 respondents in alignment with the views of Davis et al. (2021), which suggests that 10 to 40 respondents is an appropriate number of people for conducting qualitative interviews. Based on this identifying criterion, the researcher recruited 12 students, studying various degree programs at one university in the UK. Respondents were invited to take part in the study by filling a participant information sheet (see appendix 3), which contained information relating to the privacy and confidentiality of data, identification of persons supposed to participate in the investigation, and the channels of communication that have to be followed if an informant has a complaint.

The researcher recruited students to participate in the study using the purposeful sampling method. It works by allowing a researcher to gain access to participants using their best judgment (Massachusetts Medical Society, 2018). The researcher used the purposeful sampling method in the study because it was important in identifying Chinese students from the larger body of students at the selected university. Therefore, the characteristic of the selected group of informants was the main justification for the use of the purposeful sampling method. Gentles and Vilches (2017) support this statement by saying that the purposeful sampling method is appropriate for selecting respondents with unique demographic traits because it can help to identify a small group of people from a larger population of individuals that fit desired characteristics. Therefore, the research design and aim of the study, which seeks to understand the views of international students using a sample of a few respondents, influenced the selection of the sampling design.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process was informed by the research approach and data collection techniques highlighted in this chapter. To recap, the main source of information was interviews and, in line with the recommendations of Nowell et al. (2017) on the analysis of such types of data, the thematic and coding methods were used for data analysis purposes. This technique works by categorizing respondent’s views into key thematic areas that should ideally be linked with the objectives of the study (Nowell et al., 2017) The process follows six key steps, including (i) familiarization with data, (ii) coding, (iii) generating themes, (iv) reviewing themes, (v) defining and naming themes, and (vi) writing up (Ummar and Saleem, 2020). These stages of the data analysis processes were followed systematically to allow the researcher to understand how the views shared by the respondents helped to answer the research questions.

The main advantage associated with the thematic and coding method, is the theoretical freedom it offers researchers when analyzing data (Xu and Zammit, 2020). This means that they are at liberty to define interview data into distinct categories that would help to meet the objectives of the study, as the research progresses. Furthermore, the thematic and coding method eliminates the need to depend on algorithms for analysis of data, which imposes rigidity in the analysis of research data, as is the case in quantitative investigations (Morgan and Nica, 2020). Indeed, the current study required a flexible understanding of research variables because leadership is a subjective quality of educational performance. Therefore, it cannot be effectively analyzed using algorithms or fixed data analysis techniques. Therefore, the thematic and coding method helped to gather the subjective qualities of educational leadership that would be relevant in understanding the views of international students in higher education leadership.

Research Ethics

Issues relating to consent, privacy/anonymity of respondents, confidentiality and treatment of data, as highlighted by Stokes (2017), Sekaran and Bougie (2016), formed the basis for developing the ethical implications of the study. These issues are discussed below in detail.

Consent: One of the foundational principles of research ethics is obtaining informed consent from participants. According to Humphreys (2016), researchers should allow them to make a choice regarding participation in a research investigation freely and with full knowledge of what it entails. In line with these guidelines, respondents who took part in the investigation did so voluntarily. Stated differently, the researcher did not coerce them or provide financial incentives to take part in the study. The aim of doing so was to maintain objectivity in the research process by obtaining views from students who wish to give their honest views on the subject matter (Braun, Ravn and Frankus, 2020). Therefore, the researcher only sought the views of respondents who gave their consent freely to take part in the investigation.

To maintain the confidentiality of data, students who participated in the study signed an informed consent form outlining the above details (see appendix 2). It also contained provisions stipulating conditions for the exit of respondents from the investigation without any repercussions to them. In other words, participants could withdraw from the investigation without suffering any consequence. The informed consent form also contained details regarding the recording of audio tapes for the interviews. Stated differently, the respondents gave their consent to have their voices recorded by signing the informed consent form. It was primarily developed to protect the interests of the informants when obtaining data.

Anonymity and Confidentiality: The views of the respondents were presented anonymously to protect their identity from any consequences that may arise out of their participation in the study. Therefore, no identifiable variables relating to the informant’s identity, besides being international students of Chinese origin, were included in the study. This strategy is consistent with the views of Davies (2020), which encourages researchers to take necessary steps to ensure the protection of private data. The researcher also protected the respondent’s confidentiality by taking steps to make sure others do not discover the identity of the respondents. The thematic and coding method, highlighted above, helped to achieve this objective by delinking the respondent’s views from their names using codes. Thus, the findings were presented anonymously and confidentially.

Treatment of Data: The researcher stored the information obtained from the respondents safely in a computer and secured it using a password. This measure was taken to minimize the possibility of unauthorized persons accessing the data and altering it or taking information without consent (Glenna et al., 2019). This step was taken to safeguard the integrity of this study by protecting the interests of the respondents at different stages of the research process, including collection, dissemination, and analysis of data. After the research process is completed and the purpose of the investigation fulfilled, the researcher will destroy the information stored in the computer. Similarly, audio recordings of the interviews will be destroyed to prevent unauthorized use or the utilization of the same information for any other purpose besides the original intention, which is to understand the importance of integrating the voices of international students in higher education leadership. Overall, the measures taken to protect the integrity of data are consistent with the views of Melnikovas (2018), which emphasize the importance of researchers to take necessary measures to protect the integrity of information collected from respondents in qualitative interviews.

Limitations of Study

The findings highlighted above are limited to educational leadership in the higher education sector. This means that they are mostly relevant to tertiary learning institutions and not primary or secondary education levels. Furthermore, the findings highlighted above represent the views of international students who came from China and are studying in the UK. This means that their views do not represent those of students who are UK citizens but of Chinese descent. Therefore, the findings are those of students who have come from China and are currently studying in the UK.

Discussion and Findings

This chapter highlights the findings of the interview process. As mentioned in chapter three of this document, 12 respondents were interviewed by the researcher to understand their views regarding the importance of integrating the voices of international students in higher education leadership. The interview protocol contained five key pointers that focused on understanding their views regarding problem solving, creativity, policy-making, and power balance between students and teachers. The thematic and coding method was used to analyze their findings and the results are as depicted below.

Problem-Solving

Problem solving emerged as a core theme in the analysis because it is one aspect of leadership that has influenced how people allocate the value of leadership to their educational pursuits. The respondents all agreed that including alternative voices in their student leadership plans would have a positive impact on problem solving. Particularly, they mentioned that it helps to increase innovation and creativity, which are essential components of problem solving. To support this claim, one of the respondents said:

I believe that seeking our views would help to solve some of the problems we experience as students. For example, some of the issues we have encountered in school stem from the integration of minority students in the wider student body. I believe it can be addressed by drawing on the experiences of international students. For example, in my hometown, which is largely a tourist area, everyone’s views are respected. I could simply draw on these unique experiences to come up with innovative ideas that would help the school come up with better solutions for some of these problems.

Specifically, the respondents claimed that diversity helps to eliminate the monolithic way of thinking that has hampered progress in various aspects of educational development. This aspect of analysis has been highlighted in marketing research, which has shown that including alternative voices helps to relate more with consumers and retailers, thereby allowing them to better solve their problems (Tillmann et al., 2020; Nyberg, Backman and Larsson, 2020; Eshghinejad and Moini, 2016; Jabbar et al., 2020). To support this statement, one of the respondents gave an example of a local retail business in his hometown, which grew fast because of the diversity of its employees.

He further remarked that most of the employees were young people with a vision to change how people perceived their retail business. By deploying digital channels of communication, they were able to create a new audience that would not have been formed if the managers stuck to their old habits. The change helped to address one of the most difficult challenge for the company, which was to expand its market share against the background that the organization’s leaders had run out of ideas for achieving this objective. Therefore, the researcher believed that diversity helped in creating solutions to age-old problems. One of the respondents also gave an example of how his willingness to embrace diversity in his high school years when he was a school prefect helped him to carry out his tasks effectively. To support this assertion, the respondent said,

I have had my share of trouble trying to solve problems the old way using conventional reasoning but to no avail. It is only until I chose to be open-mined about these issues that I found a solution to my problems. All this happened in my last year in high school and I found it interesting that the most useful ideas I came up with stemmed from my interaction with students who I would not typically talk to. Just to bring it closer home, I have had similar experiences at home because I am a first born. Naturally, in our culture, being the first born is respectable title because your siblings tend to listen to what you have to say. At first, I used to give direction about what needs to be done but I have found a greater level of success and satisfaction working with other people. I believe it is the same for problem solving because two minds are better than one. Better yet, when minds that can draw from different experiences are put together to solve a problem, the result would be better than if one person was doing the job.

Based on the findings highlighted above, the respondents argued that including the voices of international students would enhance leadership, at least from a problem-solving perspective.

Creativity

The theme of creativity was interlinked with the concept of problem solving because the respondents seemed to be using both concepts interchangeably with the assumption that problem solving requires creativity. Therefore, similar in the manner that they unanimously agreed that alternative views would have an impact on problem solving they made the same claim when they were asked about its role in fostering creativity. Although the respondents unanimously agreed that problem-solving would foster creativity, research evidence suggests that significant cultural differences between certain segments of the international student population would make it difficult to achieve the level of creativity mentioned by the respondents (Xu, 2021; Wu, 2020; Zhang and Beck, 2017; Liang, Dai and Matthews, 2020). Particularly, an extensive body of literature explains differences between the culture of Chinese students and mainstream peers studying in the UK (Xu, 2021; Wu, 2020; Zhang and Beck, 2017; Liang, Dai and Matthews, 2020). In fact, according to Liang, Dai and Matthews (2020), this is one of the most notable struggles for Chinese students because some of them have trouble integrating with the host culture due to its foreignness. Although there is a significant difference between the culture of Chinese and UK students, there needs to be a keen understanding of the role of people’s individualism within the larger group context. This statement is true because of the need to prevent cultural bias from happening when assessing the contributions of different ethnic groups in leadership practices.

The respondents did not mention the cultural differences between China and the UK when answering the above-mentioned questions. However, one of the respondents insinuated that creativity could not thrive in an environment where there are different strains on knowledge creation and student interaction processes among peers. To illustrate this point, he said,

The biggest problem I have encountered is maintaining the social pace of my peers. Particularly, I find that hanging out in the pub with my schoolmates is a socially draining affair but I have to do it to maintain social connections with my peers. You can understand how this affects creativity because it strains social connections and poisons the environment that should ideally nurture creativity.

Overall, the informants believed that including the views of foreign students in educational leadership allows institutions of higher learning to draw on their unique experiences to foster creativity in leadership.

Policy-Making

Policy-making was the fourth theme that emerged from the study and it focused on the potential of higher education institutions to improve their policy-making processes by integrating the views of minority student groups. When the respondents were asked to give their insights regarding the effects of including the views of international students in policy-making processes, they expressed a mixture of feelings. Particularly, most of the respondents believed that including alternative views in policy-making decisions would not work because of the cultural hurdle that mainstream students and administrators have to overcome before allowing the views of minority students to be immortalized through administrative policies. This statement suggested that the respondents acknowledged the existence of a psychological barrier to the inclusion of alternative views in policy-making. To support this assertion, one of the respondents said,

You see the problem is not that I do not believe our views would not affect policy-making decisions, but we have a long way to go before we can see our contributions appear in policies developed by the university. Therefore, first, I think we should focus on just making them understand that our views are important. Later, we could make advancements in this line of reasoning by trying to encourage them to include our views in the institution’s polices.

This statement showed that some of the respondents believed that the role that international students can play in improving higher education leadership should not be viewed from a policy perspective, because it should come at the end of the inclusion process. Instead, they believed that efforts should be directed towards making school administrators understand the importance of including diverse views in their leadership practices. This statement also means that the students had little faith in their university’s leadership, especially in trusting them to go a step further from listening to them to developing policies that would eventually influence all students.

The skepticism expressed by some of the respondents regarding the willingness of the school leadership to change its policies is similar to the views of Veiga, Magalhães and Amaral (2019) who mentioned the rigidity and difficulty of changing some educational policies because they have implications on other aspects of school leadership, including curriculum development and teacher training. Therefore, the hesitation noted by some of the respondents is natural, given that institutions of higher learning need to be careful about making significant changes to their policy frameworks due to its implications on other aspects of the school’s operations (Hsieh, 2016; Abril and Gault, 2020; Souto-Otero, 2019; Fan and Zou, 2020). Broadly, based on the tone of the informant’s responses, most of them were unsure about the impact that including the voices of international students would have on their school’s policy. Most of them felt it would have little or no effect on the strength of existing policies.

Maintaining Power Balance

The last theme that emerged from the study related to the power balance between school administrators and students. Including the views of international students in the leadership practices of higher institutions of learning was seen as balancing the power between both stakeholders. All the respondents believed that there was an unequal power balance between school authorities and students. Particularly, international students were singled out as having experienced the most significant power distance because they are foreign students. To affirm this finding, one respondent said:

I do not think there is a similar power distance between teachers and international students in the conventional manner we would analyse this relationship. I say this because foreign students have more to deal with when interacting with teachers and other students in the learning environment compared to mainstream students. For example, we have challenges acclimating to our new environment – a challenge that mainstream students do not have. Therefore, they feel more connected to the teachers and their environment, thereby minimizing the power distance between them.

Language was also mentioned as a moderating variable affecting the power balance between students and teachers with three of the respondents admitting that their lack of proficiency in English hinders their engagement with teachers, thereby expanding the power distance between the two. Therefore, there was an overall feeling that international students do not benefit from the same power relationship with teachers that mainstream students enjoy, thereby limiting their participation in leadership activities.

The importance of power distance between students and teachers has been highlighted in several research studies that have focused on understanding barriers affecting teacher-student communication (Finn, Mihut and Darmody, 2021; Prewett, Bergin and Huang, 2019; Tian and Virtanen, 2020; Mittelmeier et al., 2021; Baumgartner and Councill, 2019). Some studies have contextualized the problem among Chinese students because of the cultural gap that exists between them and their UK counterparts (Xu, 2021; Wu, 2020; Zhang and Beck, 2017; Liang, Dai and Matthews, 2020). Others have investigated the same issue out of the UK and highlighted significant differences that power distance plays in affecting leadership practices in the higher education setting (Tillmann et al., 2020; Nyberg, Backman and Larsson, 2020; Eshghinejad and Moini, 2016; Jabbar et al., 2020). Nonetheless, it was confirmed that the integration of the views of international students in higher education leadership would help to reduce the power distance between them and their school administrators.

Summary

This chapter has summarized the views of 12 respondents who took part in the investigation to understand the importance of integrating the voices of international students in higher education leadership. In line with the application of the thematic and coding method in the data analysis process, four themes emerged from the study and each one of them was assigned a unique code for identifying how they help to address the quality of leadership in the higher education sector. The themes are creativity, problem-solving, maintaining power distance between students and school administrators, and policy-making. Including the voices of international students in educational leadership had a positive effect on three out of the four themes sampled – creativity, problem solving, and maintaining a healthy power distance between students and school administrators. The respondents believed that their views would have the least effect on policy-making because leaders were yet to be open about including the views of international students in school policies. Nonetheless, the findings espoused above suggest that the views of international students help to improve higher education leadership.

Reference List

Abril, C. R. and Gault, B. M. (2020) ‘Shaping policy in music education: music teachers as collaborative change agents’, Music Educators Journal, 107(1), pp. 43–48.

Aiston, S. J. and Yang, Z. (2017) ‘“Absent data, absent women”: gender and higher education leadership’, Policy Futures in Education, 15(3), pp. 262–274.

Arday, J. (2018) ‘Understanding race and educational leadership in higher education: exploring the Black and ethnic minority (BME) experience’, Management in Education, 32(4), pp. 192–200.

Banning, L. C. P. et al. (2020) ‘Determinants of cross-sectional and longitudinal health-related quality of life in memory clinic patients without dementia’, Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 33(5), pp. 256–264.

Baumgartner, C. M. and Councill, K. H. (2019) ‘Music student teachers’ perceptions of their seminar experience: an exploratory study’, Journal of Music Teacher Education, 29(1), pp. 11–25.

Bislev, A. (2017) ‘Student-to-student diplomacy: Chinese international students as a soft-power tool’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 46(2), pp. 81-109.

Blake, S. et al. (2021) ‘Reflections on joint and individual interviews with couples: a multi-level interview mode’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(2), pp. 1-10.

Brown, M. et al. (2020) ‘Parent and student voice in evaluation and planning in schools’, Improving Schools, 23(1), pp. 85-102.

Bjørkelo, B. et al. (2021) ‘Diversity in education and organization: from political aims to practice in the Norwegian police service’, Police Quarterly, 24(1), pp. 74–103.

Braun, R., Ravn, T. and Frankus, E. (2020) ‘What constitutes expertise in research ethics and integrity?’, Research Ethics, 16(1), pp. 1–16.

Chen, J. C. (2017) ‘Nontraditional adult learners: the neglected diversity in postsecondary education’, SAGE Open, 8(2), pp. 101-112.

Cheung, R. S. H., Hui, A. N. N. and Cheung, A. C. K. (2020) ‘Gifted education in Hong Kong: a school-based support program catering to learner diversity’, ECNU Review of Education, 3(4), pp. 632–658.

Cooc, N. and Yang, M. (2016) ‘Diversity and equity in the distribution of teachers with special education credentials: trends from California’, AERA Open, 7(2), pp. 1-10.

Davis, M. E. et al. (2021) ‘Novel implementation of virtual interviews for otolaryngology resident selection: reflections relevant to the COVID-19 Era’, OTO Open, 7(1), pp. 1-10.

Davies, S. E. (2020) ‘The introduction of research ethics review procedures at a university in South Africa: review outcomes of a social science research ethics committee’, Research Ethics, 16(2), pp. 1–26.

Eshghinejad, S. and Moini, M. R. (2016) ‘Politeness strategies used in text messaging: pragmatic competence in an asymmetrical power relation of teacher–student’, SAGE Open, 7(1), pp. 1-10.

Jabbar, H. et al. (2020) ‘Teacher power and the politics of union organizing in the charter sector’, Educational Policy, 34(1), pp. 211–238.

Fan, G. and Zou, J. (2020) ‘Refreshing China’s labor education in the new era: policy review on education through physical labor’, ECNU Review of Education, 3(1), pp. 169–178.

Fernando, D. (2020) ‘Challenging the cross-national transfer of diversity management in MNCs: exploring the ‘identity effects’ of diversity discourses’, Human Relations, 8(2), pp. 1-10.

Finn, M., Mihut, G. and Darmody, M. (2021) ‘Academic satisfaction of international students at Irish higher education institutions: the role of region of origin and cultural distance in the context of marketization’, Journal of Studies in International Education, 6(2), pp. 1-10.

Gentles, S. J. and Vilches, S. L. (2017) ‘Calling for a shared understanding of sampling terminology in qualitative research: proposed clarifications derived from critical analysis of a methods overview by McCrae and Purssell’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(3), pp. 1-10.

Glenna, L. et al. (2019) ‘Qualitative research ethics in the big-data era’, American Behavioral Scientist, 63(5), pp. 555–559.

Grier, S. A. (2020) ‘Marketing inclusion: a social justice project for diversity education’, Journal of Marketing Education, 42(1), pp. 59–75.

Hansen, E. R. and Clark, C. J. (2020) ‘Diversity in party leadership in state legislatures’, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 20(1), pp. 81–107.

Hatta, T. et al. (2020) ‘Crossover mixed analysis in a convergent mixed methods design used to investigate clinical dialogues about cancer treatment in the Japanese context’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(1), pp. 84–109.

He, V. F., von Krogh, G. and Sirén, C. (2021) ‘Expertise diversity, informal leadership hierarchy, and team knowledge creation: a study of pharmaceutical research collaborations’, Organization Studies, 7(8), pp. 1-10.

Hesse, A. et al. (2019) ‘Qualitative research ethics in the big data era’, American Behavioral Scientist, 63(5), pp. 560–583.

Higdon, R. D. (2016) ‘Employability: the missing voice: how student and graduate views could be used to develop future higher education policy and inform curricula’, Power and Education, 8(2), pp. 176-195.

Hsieh, C.-C. (2016) ‘A way of policy bricolage or translation: the case of Taiwan’s higher education reform of quality assurance’, Policy Futures in Education, 14(7), pp. 873–888.

Humphreys, S. (2016) ‘Research ethics committees: the ineligibles’, Research Ethics, 8(2), pp. 321-333.

Irvine, A. (2011) ‘Duration, dominance and depth in telephone and face-to-face interviews: a comparative exploration’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), pp. 202–220.

Leroy, H. et al. (2021) ‘Fostering team creativity through team-focused inclusion: the role of leader harvesting the benefits of diversity and cultivating value-in-diversity beliefs’, Group and Organization Management.

Janssens, M. and Zanoni, P. (2021) ‘Making diversity research matter for social change: new conversations beyond the firm’, Organization Theory, 8(2), pp. 1-10.

Javaid, T., Söilen, K. S. and Le, T. B. Q. (2020) ‘A Comparative study of Chinese and western MBA programs’, International Journal of Chinese Education, 7(2), pp. 89-112.

Joslyn, E. (2018) ‘Distributed leadership in HE: a scaffold for cultural cloning and implications for BME academic leaders’, Management in Education, 32(4), pp. 185–191.

Joslyn, E., Miller, P. and Callender, C. (2018) ‘Leadership and diversity in education in England: progress in the new millennium?’, Management in Education, 32(4), pp. 149-151.

Judson, G. (2021) ‘Cultivating leadership imagination with cognitive tools: an imagination-focused approach to leadership education’, Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 9(3), 321-334.

Khan, M. A. et al. (2020) ‘The interplay of leadership styles, innovative work behavior, organizational culture, and organizational citizenship behavior’, SAGE Open, 6(2), pp. 1-10.

Kim, H. K., Baik, K. and Kim, N. (2019) ‘How Korean leadership style cultivates employees’ creativity and voice in hierarchical organizations’, SAGE Open, 9(2), pp. 1-10.

Lee, C. (2020) ‘Courageous leaders: promoting and supporting diversity in school leadership development’, Management in Education, 34(1), pp. 5–15.

Leroy, H. et al. (2021) ‘Fostering team creativity through team-focused inclusion: the role of leader harvesting the benefits of diversity and cultivating value-in-diversity beliefs’, Group and Organization Management, 7(2), pp. 1-10.

Liang, Y., Dai, K. and Matthews, K. E. (2020) ‘Students as partners: a new ethos for the transformation of teacher and student identities in Chinese higher education’, International Journal of Chinese Education, 5(2), pp. 131-150.

Lyons, L., Brasof, M. and Baron, C. (2020) ‘Measuring mechanisms of student voice: development and validation of student leadership capacity building scales’, AERA Open, 7(2), pp.1-10.

Matthews, K. E. (2018) ‘Engaging students as participants and partners: an argument for partnership with students in higher education research on student success’, International Journal of Chinese Education, 3(1), pp. 42-64.

Mittelmeier, J. et al. (2021) ‘Conceptualizing internationalization at a distance: a “third category” of university internationalization’, Journal of Studies in International Education, 25(3), pp. 266–282.

Morgan, D. L. and Nica, A. (2020) ‘Iterative thematic inquiry: a new method for analyzing qualitative data’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(2), pp. 1-10.

Mullen, C. A. (2017) ‘Creativity in Chinese Schools: Perspectival Frames of Paradox and Possibility’, International Journal of Chinese Education, pp. 27–56.

Nowell, L. S. et al. (2017) ‘Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 6(2), pp. 1-10.

Nyberg, G., Backman, E. and Larsson, H. (2020) ‘Exploring the meaning of movement capability in physical education teacher education through student voices’, European Physical Education Review, 26(1), pp. 144–158.

Ogbeibu, S. et al. (2020) ‘Inspiring creativity in diverse organizational cultures: an expatriate integrity dilemma’, FIIB Business Review, 9(1), pp. 28–41.

Palaiologou, I. and Male, T. (2019) ‘Leadership in early childhood education: the case for pedagogical praxis’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 20(1), pp. 23–34.

Prewett, S. L., Bergin, D. A. and Huang, F. L. (2019) ‘Student and teacher perceptions on student-teacher relationship quality: a middle school perspective’, School Psychology International, 40(1), pp. 66–87.

Raaper, R. (2021) ‘Students as ‘animal laborans’? Tracing student politics in a marketised higher education setting’, Sociological Research Online, 26(1), pp. 130-146.

Raithel, K., van Knippenberg, D. and Stam, D. (2021) ‘Team leadership and team cultural diversity: the moderating effects of leader cultural background and leader team tenure’, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 28(3), pp. 261–272.

Saito, K. and Liu, Y. (2021) ‘Roles of collocation in L2 oral proficiency revisited: different tasks, L1 vs. L2 raters, and cross-sectional vs. longitudinal analyses’, Second Language Research, 6(1), pp. 1-10.

Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R. (2016) Research methods for business: a skill building approach. 7th edn. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Souto-Otero, M. (2019) ‘Private companies and policy-making: ideological repertoires and concealed geographies in the evaluation of European education policies’, European Educational Research Journal, 18(1), pp. 34-53.

Stokes, P. (2017) Research methods. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Study in UK. International student statistics in UK 2021. Web.

Thao, N. P. H. and Kang, S. W. (2018) ‘Servant leadership and follower creativity via competence: a moderated mediation role of perceived organisational support’, Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 6(2), pp. 1-10.

Thompson, N. A. (2018) ‘Imagination and creativity in organizations’, Organization Studies, 39(3), pp. 229–250.

Thomson, R. A. and Davignon, P. (2017) ‘Religious belief in Christian higher education: is religious and political diversity relativizing?’, Social Compass, 64(3), pp. 404–423.

Tian, M. and Virtanen, T. (2020) ‘Shanghai teachers’ perceptions of distributed leadership: resources and agency’, ECNU Review of Education, 7(1), pp. 112-118.

Tillmann, T. et al. (2020) ‘The relationship between student teachers’ career choice motives and stress-inducing thoughts: a tentative cross-cultural model’, SAGE Open, 8(2), pp. 1-11.

Ummar, R. and Saleem, S. (2020) ‘Thematic ideation: a superior supplementary concept in creativity and innovation’, SAGE Open, 8(1), pp. 443-444.

Veiga, A., Magalhães, A. and Amaral, A. (2019) ‘Disentangling policy convergence within the European higher education area’, European Educational Research Journal, 18(1), pp. 3–18.

Winther, H. (2018) ‘Dancing days with young people: an art-based coproduced research film on embodied leadership, creativity, and innovative education’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(2), pp. 1-10.

Woodley, H. and Smith, L. M. (2020) ‘Paradigmatic shifts in doctoral research: reflections using uncomfortable reflexivity and pragmatism’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(3), pp. 1-10.

Worsham, K. et al. (2021) ‘Leadership for SDG 6.2: Is diversity missing?’, Environmental Health Insights, 9(2), pp. 1-10.

Wu, H. (2020) ‘Decision-making process of international undergraduate students: an exploratory narrative inquiry into reflections of Chinese students in Canada’, ECNU Review of Education, 3(2), pp. 254–268.

Xu, C. L. (2021) ‘Time, class and privilege in career imagination: Exploring study-to-work transition of Chinese international students in UK universities through a Bourdieusian lens’, Time and Society, 30(1), pp. 5–29.

Xu, W. and Zammit, K. (2020) ‘Applying thematic analysis to education: a hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), pp. 1-10.

Winther, H. (2018) ‘Dancing days with young people: an art-based coproduced research film on embodied leadership, creativity, and innovative education’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), pp. 1-10.

Yu, J. (2021) ‘Consuming UK transnational higher education in China: a Bourdieusian approach to Chinese students’ perceptions and experiences’, Sociological Research Online, 26(1), pp. 222–239.

Zhang, Z. O. and Beck, K. (2017) ‘Seeking sanctuary: Chinese student experiences of mobility and English language learning in Canada’, International Journal of Chinese Education, 6(2), pp. 176–209.

Zheng, Y. et al. (2020) ‘Service leadership, work engagement, and service performance: the moderating role of leader skills’, Group and Organization Management, 45(1), pp. 43–74.

Appendix Section

Appendix 1: Interview Protocol

- How would you characterize the relationship between student voice and leadership in the higher education sector?

- In what ways do you think adding the voices of international students to school leadership would affect problem solving, as an important role in leadership?

- How do you think international students would influence the policy-making direction in the UK higher education setting?

- In what ways do you think involving international students in leadership positions would impact the power balance between them and other students?

- If you were to imagine a perfect scenario where students openly engaged with educators on leadership issues, how do you think it would look like?

Appendix 2: Consent Form

Topic: Importance of Integrating the Voices of International Students in Higher Educational Leadership: A Case of Chinese Students in the United Kingdom (UK)

If you are happy to participate in the study, please complete and sign the consent form below:

The following activities are optional; you may participate in the research without agreeing to the following:

Data Protection

The personal information we collect and use to conduct this research will be processed in accordance with UK data protection law as explained in the Participant Information Sheet and the Privacy Notice for Research Participants.

Name of Participant _________________ Signature Date____________________

Name of the person taking consent_________________ Signature Date_____________________

Appendix 3: Participant Information Sheet

You are being invited to take part in a research study addressing the importance including the views of international students in higher education leadership, using Chinese students studying in the UK as a case study. Before you decide whether to take part, it is important for you to understand why the research is being conducted and what it will involve. Please take time to read the following information carefully before deciding whether to take part, and discuss it with others if you wish. Additionally, feel free to seek clarification if there is anything that is not clear or if you would like more information. Thank you for taking the time to read this.

About the research

Who will conduct the research?

I will be conducting the research

What is the purpose of the research?

To investigate the importance of including the views of international students in higher education leadership, using Chinese students studying in the UK as a case study

Will the outcomes of the research be published?

The findings of the study will only be used to fulfil my academic requirements. Therefore, it will not be published outside of the university.

Who has reviewed the research project?

This research project has been reviewed by my academic supervisors and complies with the ethical procedures and guidelines governing the development of dissertations. What would my involvement be?

What would I be asked to do if I took part?

By taking part in the study, you would be expected to spare an hour of your time discussing the importance of including the views of international students in educational leadership. The interview will be done at the school cafeteria and it will be transcribed for purposes of cross-checking facts.

Will I be compensated for taking part?

No. You will be required to participate in the study voluntarily and without any financial incentive.

What happens if I do not want to take part or if I change my mind?

It is up to you to decide whether or not to take part. If you do not wish to take part, simply ignore this request but If you do decide to take part you will be given this information sheet to keep and will be asked to sign a consent form. If you decide to take part you are still free to withdraw at any time without giving a reason and without detriment to yourself. However, it will not be possible to remove your data from the project once it has been anonymised as we will not be able to identify your specific data. This does not affect your data protection rights. If you decide not to take part you do not need to do anything further. Given that the interview will be recorded, you are also at liberty to decline such a request without any repercussions. Additionally, if you feel uncomfortable recording the interview in real time, you are also free to request me to stop.

Data Protection and Confidentiality

What information will you collect about me?

In order to participate in this research project we will need to collect information that could identify you, called “personal identifiable information”. Specifically we will need to collect your:

- Name

- Contact Details

- Education program being pursued

- Age

- Gender

For the audio recordings, we will collect: Voice only during the oral interview.

Under what legal basis are you collecting this information?

We are collecting and storing this personal identifiable information in accordance with UK data protection law, which protect your rights. These state that we must have a legal basis (specific reason) for collecting your data. For this study, the specific reason is that it is in fulfilment of my degree requirements.

What are my rights in relation to the information you will collect about me?

You have a number of rights under data protection law regarding your personal information. For example you can request a copy of the information we hold about you, including audio recordings and contact details.

Will my participation in the study be confidential and my personal identifiable information be protected?

We are responsible for making sure your personal information is kept secure, confidential and used only in the way you have been told it will be used. All researchers are trained with this in mind, and your data will be looked after in the following way:

- Your data will be fully anonymised and destroyed after 5 years

- Your identity will be a code only known to the researcher

- Data will be stored in the researcher’s computer and secured using a password only known to them

- Data will solely be used for academic purposes and will not be transferred to any other agency

- The researcher will undertake data transcribing processes and the information will be coded as well

What if I have a complaint?

In case of any complaint, please contact my supervisor, whose details appear below:

- Contact details for complaints

Additional Information In Relation To COVID-19

Your participation in this research will be tape-recorded and your personal data will be processed using the thematic and coding method. This means that your personal data will not be transferred to a country outside of the European Economic Area, some of which have not yet been determined by the United Kingdom to have an adequate level of data protection. The recordings will be destroyed following the completion of data collection. Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, we have made some adjustments to the way in which this research study will be conducted that ensures we are adhering to the latest government advice in relation to social distancing as well as taking all reasonable precautions in terms of limiting the spread of the virus. You should carefully consider all of the information provided below before deciding if you still want to take part in this research study. If you choose not to take part, you need to inform the researcher. If you have any additional queries about any of the information provided, please speak with a member of the research team.

Are there any additional considerations that I need to know about before deciding whether I should take part?

No. There should be no risk to you since the research is being conducted virtually

Is there any additional information that I need to know?

Please, avail yourself on time for the interview.

What If the Government Guidance Changes?

If there are changes in government guidelines, we will communicate on an appropriate action accordingly

What If I Have Additional Queries?

Please contact my supervisor using the contact details outline here

Appendix 4: Introductory Letter

Dear Participant,

As part of my educational requirements at the University, I am completing a research project on understanding the importance of integrating the views of international students in educational leadership using Chinese students in the UK higher education sector as a case study. Would you be interested in taking part?

The investigation will not be about you specifically but about the collective views of Chinese (and by extension international students) in educational leadership in the UK higher education sector. If you would like to take part, I would invite you to take part in an interview in which I would ask you some questions about your experiences. This is likely to last between 30-45 minutes.

I will conduct the interview as the researcher. Anyone who is a student in the university and who hails from China can take part in the investigation, so feel free to invite your colleagues who fit the above profile and would be open to taking part in the study.

Few risks are involved in the interview and if you are free to stop at any time, you can.

If you want to take part, please reply to this email and let me know.

Best wishes, _______________________