Introduction

K-education constitutes one of the most fundamental components of social, cognitive, behavioral, and emotional growth and development for each child and teenager. A well-developed k-12 curriculum enables students to develop and strengthen basic skills such as reading and writing. It exposes children to new experiences which give them an excellent opportunity to gain new knowledge, establish friendships, and hone basic social skills. However, unfortunately, students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face a myriad of challenges and barriers to accessing k-education. Even though the overall situation is much better, and more people nowadays have a positive and supportive attitude toward kids with special needs, there are still many issues that prevent autistic learners from getting quantity education. In their journal article, Ferri and Connor 2005) argue that “racialized notions of ability functioned to uphold segregated schooling and justify the use of special education as a tool of racial re-segregation” (p. 453). Therefore, the purpose of this research paper is to review the existing literature about accessibility for students with autism in education in K-12. Trends in the integration of autistic pupils in mainstream education, problems faced when including them in conventional classrooms, and effective interventions for accommodating students with this learning and developmental disorder are thoroughly discussed.

General Situation with ASD Students’ Accessibility in Education

In 1954, the Supreme Court made a landmark ruling on school segregation in the United States (US). In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Oliver Brown, an African American student, was denied the chance to study in a white school (Peters, 2019). The presiding justices made a unanimous decision that segregating children in public schools in the US was unconstitutional. Justice Warren declared that “the practice of segregating students by race creates in Black students ‘‘a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way very unlikely ever to be undone” (Ferri and Connor 2005, p. 455). Seven decades have elapsed since the overarching decision; a thought-provoking question arises: What progress has the US public education system made toward ensuring that all children in America have equal access to high-quality learning opportunities? In an attempt to answer this question, this section documents trends in racial segregation in US public education, with a special focus on students with ASD.

There have been notable efforts to make US public education accessible to all students. However, since the Supreme Court’s milestone decision on Oliver Brown’s case, the country has made little progress toward improving integration in schools throughout the country. According to Ferri and Connor (2005), this problem manifested itself in the disproportional representation of students of color in special education programs in the country. Overall, public schools in the US remain alarmingly segregated. The original purpose of special education in America was to provide school-going children with greater educational opportunities. However, Ferri and Connor (2005) argue that it has contributed to the insidious process of segregating students with disability.

Before 1975, particularly under the Jim Crow laws, children and teenagers with autism spectrum disorder did not have any accessibility to education. Most of them had to study in specialized schools or at home, where they were completely separated from their peers without disabilities (Partlo, 2018). Fortunately, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 first introduced the idea of a right to public education for disabled students. The amendment of this statute – the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) – mandates all public educational institutions to offer free and developmentally-appropriate education to all eligible students aged between three and 21 years. According to this legislation, public schools have a legal duty to “provide individualized special education for students with certain disabilities” (Partlo, 2018, p. 12). Since then, school-going children with autism have gained an opportunity to take part in mainstream k-12 education together with other children without disabilities.

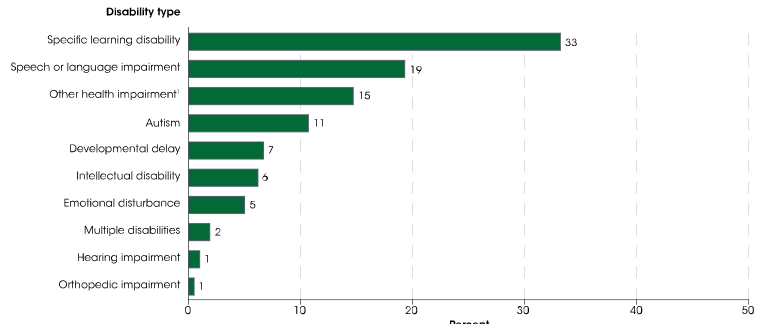

A recent report from the National Center for Education Statistics provides a comprehensive review of current trends in special education in the US. The latest annual report indicates a significant increase in the proportion of pupils receiving special education mandated by IDEA between 2000 and 2019. The number of learners under special education scaled up from 6.3 million to 7.1 million between 2000-1 and 2018-19 school years (NCES, 2020). The period stretching from 2011 to 2019 recorded the highest increase, with the population of special needs learners rising from 6.4 million to 7.1 million (NCES, 2020). As illustrated in Figure 1 below, ASD is one of the leading disabilities among special education students in the US.

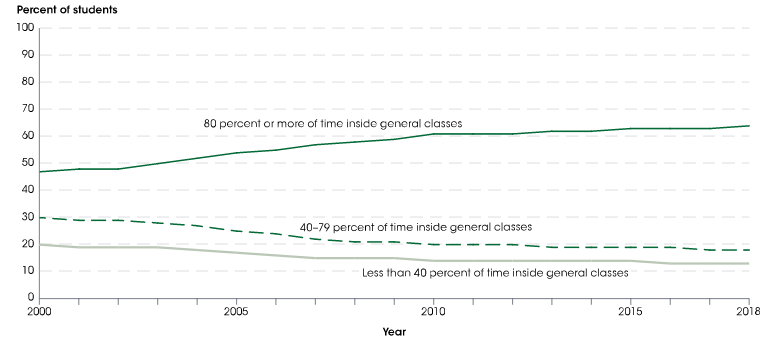

Mainstreaming or inclusion – the current model of special education – has become more prevalent over the last few decades, and has enhanced accessibility for students with ASD in education in the country. Recent estimates show that a large percentage of learners with ASD and other disabilities are spending 80% or more of their time in school in regular classrooms (NCES, 2020). As demonstrated by Figure 2 below, the percentage of students with a various impairments who spend at least 80% of their school time in general classes has increased steadily since 2000, compared to those who spend 40% to79% and less than 40% of their school time (NCES, 2020).

However, despite the considerable progress toward enhancing autistic children’s access to education, this subgroup remains marginalized in mainstream k-12 education. Mainstreaming has contributed to the segregation of k-12 education in the country. A comprehensive investigation by the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica Illinois provides a clear picture of the state of segregation of children with disabilities across Illinois (Richards et al., 2019). The investigators collected and undertook in-depth analyses of vast amounts of records that state law public schools to create when using seclusion. The results of the inquiry revealed a staggering 20,000 incidents of seclusion for the period stretching from 2017 to 2018 (Richards et al., 2019). Out of the total cases established, approximately 12,000 featured adequate information for determining reasons that led to the timeout. In a significant portion of the incidents, school personnel failed to provide a clear justification for segregating students with autism (Richards et al., 2019). The statistics demonstrate the alarming rate at which learners with ASD face challenges accessing equal, quality educational opportunities in the US public education system.

This problem appears to be common in other developed countries across the world. In the United Kingdom (UK), for example, the exclusion of autistic pupils and children suffering from other learning and developmental disabilities takes two major forms: fixed-term or permanent (Brede et al., 2017). In fixed-term, autistic children are secluded for a short period due to their challenging behavior. In permanent exclusion, school-age kids are transferred from mainstream schools to alternative, short-term facilities such as pupil referral units (Brede et al., 2017). School exclusion remains a prevalent practice in the UK education system. A survey of 980 parents conducted by a consortium of parent-advocacy organizations illuminate the scale of segregation of school-age children with ASD. About one in five of the parents who participated in the study stated that their children had received at least one fixed-term, while one in twenty reported at least one incidence of permanent exclusion (Brede et al., 2017). The most surprising revelation was that one-third of the parents claimed that their kids had at least a history of informal exclusion and that schools did not document such violations.

School segregation in the UK manifests itself in astonishing forms. Some of the discriminatory practices included encouraging children with ASD to transfer to another school or consider other alternatives such as homeschooling, denying them a chance to participate in school activities such as trips, and sending them home for any period (Brede et al., 2017). Such events demonstrate that autistic pupils still encounter grueling experiences in mainstream k-12 education across the world.

Challenges Faced in Integrating Autistic Children in K-Education

Lack of Documenting and Reporting Use of Seclusion

Many factors hinder efforts to integrate pupils with ASD into regular classrooms. One major problem is that the exclusion of learners from this particularly vulnerable group often goes unnoticed. According to the investigation in Illinois, state officials in the education sector are unaware of most of the disclosed violations due to the failure of learning institutions to monitor and report how they utilize the practice of exclusion (Richards et al., 2019). Besides that, the outcome of this study showed that parents and guardians are often given little or no information concerning what their children face in school. Such practices prove to be detrimental to efforts by state and federal governments to enhance accessibility for children with ASD and other learning and developmental disorders. This problem is aggravated by the failure of local, state, and federal education officials to review seclusion reports. According to the report of the investigation into this practice in Illinois, a number of school district officials in the state stated that they did not evaluate reports on the segregation of autistic learners in their schools. They only review the reports when they are required by other agencies.

In addition to this laxity, the investigators established that this trend is consistent across the Illinois State Board of Education, which manifested itself in the blatant failure to collect relevant data on how schools in the region utilize isolated timeout (Richards et al., 2019). Perhaps the most point of concern was the continued use of the same guidelines for 20 years without making any effort to review and update them. These flaws are a cause of worry considering that state law requires schools and district officials to document a detailed report every time they use seclusion. Zena Naiditch, the founder and leader of a non-governmental organization known as Equip for Equality echoed this issue. Naiditch cautioned that “having a law that allows schools to do something that is so traumatic and dangerous to students without having some sort of meaningful oversight and monitoring is really, really troubling” (Richards et al., 2019). This state of affairs calls for increased accountability on the part of state district school officials and teachers, administrators, and other employees of individual learning institutions.

Intrinsic Characteristics of Children with ASD

Autistic children exhibit certain unique intrinsic attributes that compromise efforts to include them in mainstream k-education. One aspect of the limited accessibility of autistic students in public schools is the challenges that school workers encounter while handling students with ASD and other learning and developmental problems. There is a general consensus among educational scholars and practitioners on the point that most autistic children who are secluded are difficult to manage in regular classrooms (Richards et al., 2019). This problem is evident in the Illinois investigation where some school staff members reported struggling to handle disruptive, and sometimes violent behavior of autistic children. According to the investigation, some pupils bite, kick, or even hit others. These findings are confirmed by an empirical study that established that autistic children exhibit difficulties in controlling their emotions and behaviors (Kanakri et al, 2017). Some employees said that they are forced to seclude some students who exhibit such behaviors in order to ensure the safety of every kid in the classroom (Richards et al., 2019). Another justification for using this practice was to help students learn ways of calming themselves.

However, empirical evidence demonstrating a higher tendency of violence and aggression among individuals with autistic conditions remains scarce. Allely et al. (2017) challenge previous research findings supporting the claim that people with ASD exhibit higher chances of engaging in aggressive or offending behavior. On contrary, Allely et al. (2017) argue that individuals who suffer from this developmental problem may be at a heightened risk of falling victims rather than perpetrating violence. The scholars further clarify that a small portion of autistic people tends to be violent. Fitzgerald (2015) contributes to this debate by asserting that individuals with neurodevelopmental problems are rarely responsible for mass killings. On the contrary, Fitzgerald (2015) argues that ‘straight’ people are often the most common perpetrators of most shootings in social places such as learning institutions and entertainment joints.

Allely et al. (2017) conducted an empirical study to substantiate these claims. They reviewed previous mass shooting incidents captured in Mother Jones’ database to establish whether the perpetrators exhibit ASD characteristics. Results of the investigation showed that individuals with autistic features accounted for only six out of the 75 mass murder cases, representing 8% of the perpetrators. Despite being a conservative estimate, these statistics clearly indicate that neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly ASD, may have an influence on, but not be the main cause of extremely violent behaviors such as murdering dozens of people in cold blood. Therefore, aggressive behaviors reported above may not provide strong evidence to exclude pupils with ASD from regular k-12 classrooms.

Increasingly Complex Demands of School Life

Increasingly complex demands and challenges brought out by today’s school life contribute to the persistent low integration of autistic students in mainstream education. Brede et al. observed that “it is possible that school exclusion – at least for a significant minority of autistic children and young people – is an inevitable response to difficulties dealing with the increasingly complex demands of school life” (p. 2). The increasing pressures placed on students’ academic achievement make it difficult for schools and teachers to accommodate autistic children in regular classrooms. Similarly, the array of such demands may also make it difficult for pupils with ASD and other learning impairments to cope with already existing challenges. Some of the difficulties include establishing and maintaining friendships, handling disagreements with peers in school, organizing and managing their school work, responding to often overwhelming multiple stimuli in the school and classroom, and regulating negative emotions and behaviors (Allely et al. 2017; Brede et al., 2017).

Results of the exploratory survey conducted by Kanakri et al. (2017) shed more light on the increasingly complex demands of contemporary school life. The researchers observed that physical distractions such as noise can have an adverse impact on autistic students’ health and wellbeing in school. A majority of the instructors who were surveyed reported noise control as one of the major concerns when dealing with children with ASD (Kanakri et al., 2017). The teachers who participated in this investigation suggested the need to install think or soundproof walls and carpets in classrooms to help address the challenges associated with noise. The findings of this research demonstrate the architectural and structural accommodations that school districts and all learning institutions may need to put in place to provide safer and more accessible education to children with ASD.

Considerations for Enhancing Accessibility for Students with ASD in Education

Certainly, it is possible for educators to positively influence the schooling experiences of children with an autism spectrum disorder. To begin with, teachers should try to find a balance between providing help, support, and participation and showing pity and extra attention, which may be negatively perceived by both children with autism and their typically developing peers (Denning & Moody, 2013). Next, it is important for educators to adopt strategies that will reduce autistic students’ anxiety and promote their interest in learning. Providing such schoolers with special space for sensory reactions to the environment will contribute to their increased attention to the class materials (Marsh et al., 2017).

Further, it is vital to take into consideration the unique features of this disorder when making a lesson plan. For instance, a teacher may want to break big tasks into smaller ones that are more manageable for autistic kids (Deschaine, 2018). It will also allow such students to gradually complete their assignments and be happy and more engaged due to the successful completion of the previous parts of the task. Visual timetables will make sure that autistic students are aware of and ready for the new work (Bolourian et al., 2018). Finally, ensuring a positive environment in the classroom, providing support, and helping with being socialized are also the steps that a teacher may and should make to facilitate the learning of ASD schoolers.

Besides that, positive student-teacher relationships play an important role in enhancing accessibility for learners with ASD in k-12 education. Unfortunately, the transition to early schooling may be especially difficult and even frightening for young children with autistic spectrum disorder (Marsh et al., 2017). That is why, according to Bolourian et al. (2018), “the quality of the student-teacher relationship (STR) is seen as crucial to successful academic outcomes and a strong predictor of long-term behaviors” (para. 5). It is believed that supportive, trusting, and close relationships between autistic learners and their educators may greatly contribute to the development of stronger social skills and an increased likelihood of peer acceptance (Bolourian et al., 2018).

Conclusion

To draw a conclusion, one may say that the general picture of accessibility for students with autism in education in K-12 appears to be rather optimistic. Most teachers nowadays do their best to support learners with special needs, increase their good experiences, and help them adapt to the educational environment. Various programs and practices aimed at making the school community more engaged in supporting students with autism spectrum disorder are of significant help. What is more, the fact that teachers now have increased access to different materials, refresher courses, and competent information on the education of children with special needs play an essential role in providing such schoolers with proper K-12 education? Though substantial modifications and improvements are still required, it is possible to say that the process of engaging autistic children and teenagers in general education classrooms that started in 1975 and continues to this day is successful.

References

Allely, C. S., Wilson, P., Minnis, H., Thompson, L., Yaksic, E., & Gillberg, C. (2017). Violence is rare in autism: when it does occur, is it sometimes extreme? The Journal of Psychology, 151(1), 49-68. Web.

Bolourian, Y., Stavropoulos, K. K. M., & Blacher, J. (2018). Autism in the classroom: Educational issues across the lifespan. In M. Fitzgerald (Ed.), Autism spectrum disorders: Advances at the end of the second decade of the 21st century. IntechOpen.

Brede, J., Remington, A., Kenny, L., Warren, K., & Pellicano, E. (2017). Excluded from school: Autistic students’ experiences of school exclusion and subsequent re-integration into school. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 1-20. Web.

Denning, C. B., & Moody, A. K. (2013). Supporting students with autism spectrum disorders in inclusive settings: Rethinking instruction and design. Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 3(1), 1-21.

Deschaine, M. (2018). Supporting students with disabilities in K-12 online and blended learning. Michigan Virtual University.

Ferri, B., & Connor, D. (2005). Tools of exclusion: Race, disability, and (re) segregated education. Teachers College Record, 107(3), 453-474. Web.

Kanakri, S. M., Shepley, M., Varni, J. W., & Tassinary, L. G. (2017). Noise and autism spectrum disorder in children: An exploratory survey. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 85-94. Web.

Marsh, A., Spagnol, V., Grove, R., & Eapen, V. (2017). Transition to school for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(3), 184–196.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). The condition of education: Students with disabilities. Web.

Partlo, S. (2018). Meeting learning needs of children with autism spectrum disorder in elementary education (Publication No. 5952) [Doctoral study, Walden University]. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies.

Peters, A. L. (2019). Desegregation and the (dis) integration of Black school leaders: reflections on the impact of Brown v. Board of education on Black education. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(5), 521-534. Web.

Richards, J., S., Cohen, J.S., & Chavis, L. (2019). The quiet rooms. Chicago Tribune. Web.

Wei, X., Wagner, M., Christiano, E. R., Shattuck, P., & Yu, J. W. (2015). Special education services received by students with autism spectrum disorders from preschool through high school. Journal of Special Education, 48(3), 167-179.