Analysis and Evaluation of Pedagogical Principles

Pedagogical Principles in First Aid

Investigating teaching techniques, or pedagogy, is important for teaching students first-aid information and skills. Some pedagogical ideas that can be used in first aid are listed below. Firstly, active learning emphasizes students’ involvement in the instructional procedure (Ren et al., 2021). To help students learn useful first-aid abilities, engaging instruction in the first-aid field uses hands-on teaching methods, including models and roleplaying games.

Additionally, experiential education is a method of instruction that incorporates active learning (Morris, 2020). Learning by doing in the first aid field entails using procedures in made-up emergencies.

Effectiveness of Creative and Innovative Approaches

Some instances of inventive and creative methods for teaching first aid are discussed. In simulation exercises, real-world situations are fabricated, and learners are asked to use their first-aid knowledge to respond effectively (Bucher et al., 2019). This method can be especially effective when teaching students how to handle emergencies.

Additionally, the gamification technique uses games and interactive exercises to impart first aid knowledge. With this strategy, it may be especially easy to keep students interested and motivated to remember what they have learned (Sailer & Homner, 2020). In light of student involvement, information retention, and skill transfer, novel and creative teaching methods can be assessed for their efficacy.

Design of Lesson Plans and Schemes of Work

Initial and Diagnostic Assessments

Initial evaluations assist in determining the learners’ prior knowledge, areas of strength, and areas in need of development. Diagnostic tests are designed to pinpoint the precise knowledge and skills that students need to gain (Heitzman et al., 2019). Various instruments can be used for initial and diagnostic evaluations, such as surveys, tests, conversations, and observations. Once this data is gathered, the teacher can use it to create a lesson plan or a schedule of assignments that suits each student’s inclinations and needs. For instance, if teachers discover that some students already have first-aid training and expertise, they might create exercises that build on those skills.

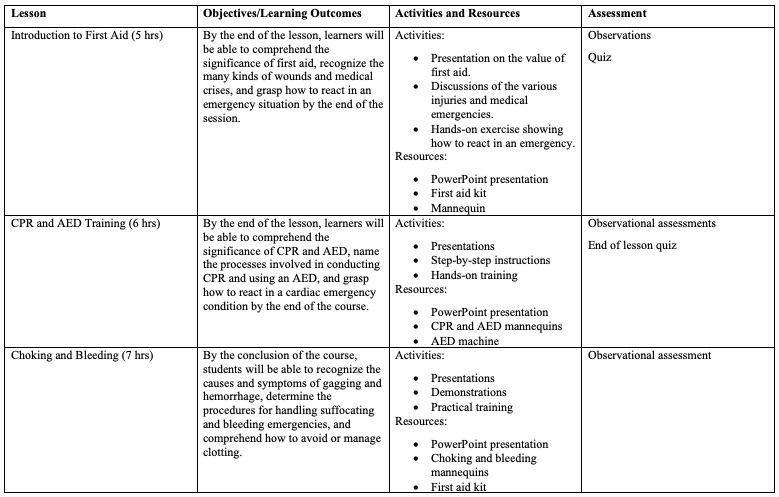

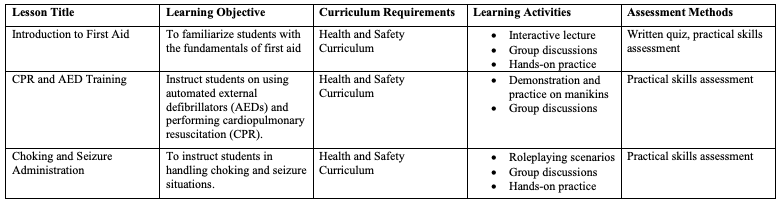

Scheme of Work

Teaching and Learning Plans

Opportunities to Provide Feedback and Inform Inclusive Learning

Utilizing preliminary evaluations at various stages of the teaching process is one way to give students a chance to give feedback. These tests can be used to gauge students’ comprehension of the subject matter and spot any potential weak points (Schildkamp et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021). Then, using this knowledge, teachers can modify their pedagogical approaches and, as necessary, offer more assistance. Moreover, using student assessments is another way to present chances for feedback (Cladera, 2021; Martin et al., 2019). This entails asking students to assess their educational experience and offer comments on the instructor’s success, the standard of the available tools and supplies, and the educational setting as a whole.

Incorporating Principles, Theories, and Models of Learning in Own Practice

As a first aid expert, I performed the following actions to prepare for inclusive teaching and learning. Firstly, I considered various educational hypotheses, including behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, and social learning theory, to comprehend how kids learn and what instructional techniques are most productive. I employed numerous teaching techniques to engage pupils and accommodate various learning methodologies, including demonstrations, models, and roleplaying. Secondly, to ensure learners got the topics being taught and had the opportunity to ask questions, if necessary, I used communication techniques like clarity, suggestions, and attentive listening.

Application of Theories in Behavior Management

Theories of Behavior Management

Firstly, according to the behaviorist concept of instruction, connections between an event and a reaction can be used to explain how people act. Behaviorism stresses the utilization of incentives and sanctions to mold and reinforce desired actions (Mayer, 2019). Pursuant to this idea, beneficial reinforcement makes a behavior more likely to be repeated, whereas punishment makes a behavior less likely to be replicated (Hayden, 2022).

Secondly, according to the social learning hypothesis, people pick up knowledge by watching others behave and the following results (Ahn et al., 2020). The concept of social education underlines the value of imitating appropriate conduct and allowing students to see and perform these attitudes. Finally, humanistic theory strongly emphasizes the value of personal development and self-actualization (Purswell, 2019; Muhajirah, 2020). The humanistic perspective highlights the value of providing an inviting and motivating educational setting that supports students’ development and growth.

Establishing and Sustaining a Safe, Inclusive Learning Environment

Belbin team roles are the various positions team members can fill, such as “plant,” which creates ideas, or “implementer,” which carries them out. Teachers may ensure they build an extensive and equitable unit that can function well together by knowing the various team roles (Rahmani et al., 2022). Tuckman’s stages of group development outline the several phases that a group experiences while cooperating, including establishing, storming, developing standards, executing, and adjourning (Putro et al., 2020). By being aware of these phases, educators can foresee potential difficulties and assist their pupils in finding constructive solutions.

How Own Practice Has Incorporated Theories of Behavior Management

The Belbin team roles hypothesis is one of the theories I employed. This notion shows everyone has different teamwork skills and limitations (García-Ramírez, 2021). I applied this principle by ensuring that I provide students with assignments that are appropriate for their abilities and strengths, encouraging them to feel more assured and involved in the educational procedure. I also considered alternative behavior modification theories, like Skinner’s behaviorism, which highlights constructive criticism, and Bandura’s notion of social learning, which underlines the value of imitation and observation (Watters, 2023). I developed a welcoming and encouraging learning atmosphere where learners are appreciated, acknowledged, and inspired to learn by utilizing these beliefs.

Development of Inclusive Teaching Resources

Resources that Promote Equality and Value Diversity

The resources listed below are a few examples of those who vigorously advocate equality and pluralism. Offering first aid material in many languages can be useful for students whose mother tongue is another language other than English. This can include flyers, manuals, or online sources that offer fundamental first-aid knowledge in various languages (Lotherington et al., 2019). Visual aids can be helpful for students who have difficulty reading or comprehending textual guidelines (Bagila et al., 2019). For instance, teaching first aid practices via images, diagrams, or films might help students comprehend and remember the procedures.

Flexibility and Adaptability in Use of Inclusive Teaching and Learning Approaches

Utilizing various instructional strategies and materials to accommodate various learning preferences is one way to guarantee inclusivity in first-aid training. For instance, the use of films, diagrams, and drawings may be beneficial for some students who learn best visually (Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2019). Others, who learn best through aural means, could profit from listening to podcasts or watching lectures that have already been recorded. It is crucial to take into account the needs of students who are disabled in addition to utilizing numerous instructional strategies and materials (Bagila et al., 2019). For instance, students with vision impairments could need resources in audio or braille versions.

Ways to Promote Equality and Value Diversity

Regardless of their backgrounds, creating an inviting school environment for all pupils is crucial. This can be done by putting up posters and photos that honor diversity and cultivating a welcoming classroom environment for all children (Ainscow, 2020). Additionally, it would be beneficial for equality if instructional materials like presentations, books, and videos included a variety of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Therefore, all learners will feel appreciated and included as a result of this. Finally, including plurality in lesson plans ensures that they are inclusive and reflect various viewpoints (Schachner, 2019). This can be accomplished by including narratives and illustrations that illustrate different walks of life.

Communicating with Learners and other Learning Professionals

Successful interaction is essential to ensure that students convey their requirements and that teachers can react effectively. This may entail utilizing various communication techniques, including written, vocal, and visual assistance (Ally, 2019). It is crucial to make sure that students, irrespective of their experience or degree of ability, can understand the discourse. It is critical to interact with students and teachers, other participants in the educational procedure, and instructional practitioners (Ally, 2019). Communication may entail collaborating with educators, support personnel, and other experts to guarantee that all students obtain the assistance they require to reach their maximum potential.

Incorporation of Theories, Principles, and Models of Learning and Communication

Firstly, I took into account Bandura’s idea of social learning, which highlights the value of roleplaying and observing others. This notion helped me ensure that my teaching strategies included different personalities and allowed students to gain insight from other learners (Stanley, 2020). I also considered the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) tenets which underline the significance of developing versatile and malleable teaching strategies that can be quickly modified to fit the requirements of all learners (Cumming and Rose, 2022). In addition, I thought about communication principles, including active listening, crystal-clear articulation, and non-verbal interaction.

Design and Implementation of Assessments

Assessments that Meet Individual Needs of Learners

Roleplay evaluations let students exhibit their first-aid expertise by acting out a situation in a secure and controlled setting. An educator may ensure that every student can relate to the evaluation and feel at ease by offering numerous simulations depicting various situations and obstacles (McGarr, 2021). In addition, various students can take multiple-choice assessments, irrespective of their literacy or comprehension skills (Kaipa, 2021). The options provided should reflect various societal, cultural, and language experiences and be structured to evaluate the pupil’s awareness of and grasp of first aid fundamentals.

Flexibility and Adaptability Using Types of Assessments

Observation is a useful tool for evaluating practical abilities like first aid. This entails keeping track of the performance of the pupils while you watch them conduct first aid techniques (Soar et al., 2019). Students’ first aid skills, including their capacity to conduct CPR, bandage wounds, and cure burns, are evaluated through practical exams. Practical evaluations can be carried out in real-world or simulated settings (Andrade & Brookhart, 2020). Lastly, written tests can be used to evaluate a student’s comprehension of first aid’s conceptual components, including the indications and symptoms of different medical illnesses and the proper ways of delivering prescriptions.

Uses of Assessment Data

Assessment data are essential for tracking learners’ success, achievement, and advancement. Analyzing assessment data from different sources, such as formative and summative tests, self and peer evaluations, and observational notes, can help one to accomplish this. Setting goals for learners and encouraging them to reach them is a powerful motivator. Then, one can use this information to create SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) objectives (Schildkamp, 2019). Data from assessments can also be used to plan for subsequent sessions by highlighting the areas in which students require more assistance or reinforcement. Lastly, the results of evaluation information can be utilized to monitor students’ progress over time, spot trends, and modify their teaching methods appropriately.

Communicating Assessment Information to Other Professionals

One method of disseminating evaluation data is using progress reports to implement first aid principles in actual situations. Students, their guardians or legal representatives, and other educators who participate in their learning, such as educators, school counselors, and medical experts, can all access these documents (Sindhu et al., 2019). In addition to advancement reports, conducting periodic conversations with the right people is crucial to discuss the student’s development and pinpoint any areas that can benefit from extra help. Encounters with pupils, their parents or legal guardians, other educators, and other education-related professionals may fall under this category.

Assessment Practice and Theories, Principles, and Model of Assessment

Bloom’s taxonomy, which divides educational goals into six stages of cognitive difficulty, is one of the hypotheses I considered. Using this framework, I ensured that my tests covered various intellectual levels, which helped me evaluate how well my students comprehended the topic (Crompton et al., 2019). The Assessment for Learning (AfL) approach, which emphasizes the value of feedback to students, is another model I thought about. AfL assists in identifying areas of potential and vulnerability, allowing students to develop their knowledge and abilities (Westbroek et al., 2020). Moreover, when creating assessments, I considered validity, dependability, and fairness.

Application of Core Skills in Teaching

Minimum Core Elements

Conversation, comprehension, calculation, and digital abilities are the fundamental components. These fundamental core components should be considered and incorporated into the instructional schedule by the instructor when designing inclusive instruction and education. For instance, the instructor can improve interaction and digital skills when teaching First Aid by using visual aids and films. To ensure that every learner can participate and benefit from the learning procedure, the instructor can present the lesson using various teaching tactics that cater to varied learning techniques and skills.

Applying Minimum Core Elements in Planning, Delivering, and Assessing

The student’s different requirements and capacities must be considered while designing inclusive educational experiences. Thus, this may entail modifying instructional materials to accommodate various learning preferences and utilizing various approaches to engage and encourage learners (Santos & Castro, 2021). To deliver equitable education and instruction, a secure and warm atmosphere must be created. This can involve encouraging all pupils to participate actively and to behave positively.

Regardless of the learner’s background or aptitude, comprehensive learning and instruction assessment involves evaluating their development and achievements (Santos & Castro, 2021). As such, this can involve pointing out areas for growth and offering assistance and input to pupils as they enhance their abilities and knowledge.

Evaluation and Improvement of Teaching Practices

Theories and Models of Reflection

Gibbs’ reflective cycle is one theoretical framework for reflection that I may use. The definition, sensations, assessment, examination, summary, and execution plan are the six stages that make up this approach. Utilizing the model, I could describe the circumstance, recognize my emotions and opinions, review what happened, consider what I might have done differently, come to inferences, and create an action plan to enhance my instruction (Markkanen et al., 2020). Following all the mentioned steps, I can reflect on how I teach employing this framework.

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is another philosophical contemplation model I can apply. Concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation are the four stages of this approach (Morris, 2020). This strategy allows me to conceptualize fresh concepts and methods, explore novel pedagogical methods, and focus on my teaching techniques by experiencing the scenario, watching it, and reflecting on it.

Ways to Improve Own Practice in Planning, Delivering, and Assessing

The following tactics can be considered to enhance your practice of designing, delivering, and evaluating inclusive teaching and learning. Finding areas that need improvement can be done by reflecting on one’s teaching methods. One can examine their course planning, delivery method, and evaluation techniques to find any potential biases or exclusions. By ensuring that the educational setting is set up to suit learners who are disabled and that all pupils are accepted, one may promote inclusivity by creating an inviting setting.

Additionally, utilizing numerous teaching techniques can support and engage various learning styles. For instance, one can encourage inclusivity by utilizing collaborative tasks, group projects, and visual aids (Puspitarini & Hanif, 2019). As a result, employing inclusive language can support the development of a sense of community among pupils (Barcena et al., 2020). In place of “he” or “she,” an educator should use the plural pronoun “they” to avoid using gender-specific vocabulary.

References Lists

Ahn, et al. (2020) “Do as I do, not as I say”: using social learning theory to unpack the impact of role models on students’ outcomes in education.’ Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(2), pp.1-12. Web.

Ainscow, M. (2020) ‘Promoting inclusion and equity in education: lessons from international experiences.’ Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), pp.7-16. Web.

Ally, M. (2019) ‘Competency profile of the digital and online teacher in future education.’ International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(2), pp.1-18. Web.

Andrade, H.L. and Brookhart, S.M. (2020) ‘Classroom assessment as the co-regulation of learning.’ Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(4), pp.350-372. Web.

Bagila, et al. (2019) ‘Teaching primary school pupils through audio-visual means.’ International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 14(22), pp.122-140. Web.

Barcena, et al. (2020) ‘An approximation to inclusive language in LMOOCs based on appraisal theory.’ Open Linguistics, 6(1), pp.38-67. Web.

Bucher, et al. (2019) ‘VReanimate II: training first aid and reanimation in virtual reality.’ Journal of Computers in Education, 6, pp.53-78. Web.

Cladera, M. (2021) ‘An application of importance-performance analysis to students’ evaluation of teaching.’ Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 33(4), pp.701-715. Web.

Crompton, et al. (2019) ‘Mobile learning and student cognition: a systematic review of PK‐12 research using Bloom’s Taxonomy.’ British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(2), pp.684-701. Web.

Cumming, T.M. and Rose, M.C. (2022) ‘Exploring universal design for learning as an accessibility tool in higher education: a review of the current literature.’ The Australian Educational Researcher, 49(5), pp.1025-1043. Web.

García-Ramírez, Y. (2021) ‘Belbin’s team roles and their performance in road design courses: a study with undergraduate and postgraduates students.’ Spaces, 42(1), pp.176-188. Web.

Hayden, J. (2022) Introduction to health behavior theory. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Heitzman, et al. (2019) ‘Facilitating diagnostic competences in simulations: a conceptual framework and a research agenda for medical and teacher education.’ Frontline Learning Research, 7(4), pp.1-24. Web.

Kaipa, R.M. (2021) ‘Multiple choice questions and essay questions in curriculum.’ Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(1), pp.16-32. Web.

Lotherington, et al. (2019) ‘Analyzing the talking book Imagine a world: a multimodal approach to English language learning in a multilingual context.’ Text & Talk, 39(6), pp.747-774. Web.

Markkanen, et al. (2020) ‘A reflective cycle: understanding challenging situations in a school setting.’ Educational Research, 62(1), pp.46-62. Web.

Martin, et al. (2019) ‘Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: course design, assessment and evaluation, and facilitation.’ The Internet and Higher Education, 42, pp.34-43. Web.

Mayer, R.E. (2019) ‘Thirty years of research on online learning.’ Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(2), pp.152-159. Web.

McGarr, O. (2021) ‘The use of virtual simulations in teacher education to develop pre-service teachers’ behavior and classroom management skills: implications for reflective practice.’ Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(2), pp.274-286. Web.

Moreno-Guerrero, et al. (2020) ‘Educational innovation in higher education: use of role-playing and educational video in future teachers’ training.’ Sustainability, 12(6), pp.1-14. Web.

Morris, T.H. (2020) ‘Experiential learning: a systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model.’ Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), pp.1064-1077. Web.

Muhajirah, M. (2020) ‘Basic of learning theory: (behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism, and humanism).’ International Journal of Asian Education, 1(1), pp.37-42. Web.

Purswell, K.E. (2019) ‘Humanistic learning theory in counselor education.’ Professional Counselor, 9(4), pp.358-368. Web.

Puspitarini, Y.D. and Hanif, M. (2019) ‘Using learning media to increase learning motivation in elementary school. Anatolian Journal of Education, 4(2), pp.53-60. Web.

Putro, et al. (2020) ‘An intelligent agent model for learning group development in the digital learning environment: a systematic literature review.’ Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, 9(3), pp.1159-1166. Web.

Rahmani, et al. (2022) ‘Team composition in relational contracting (RC) in large infrastructure projects: a Belbin’s team roles model approach.’ Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 29(5), pp.2027-2046. Web.

Ren, et al. (2021) ‘A survey of deep active learning.’ ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54(9), pp.1-40. Web.

Sailer, M. and Homner, L. (2020) ‘The gamification of learning: a meta-analysis.’ Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), pp.77-112. Web.

Santos, J.M. and Castro, R.D. (2021) ‘Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in action: application of learning in the classroom by pre-service teachers (PST).’ Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 3(1), pp.1-8. Web.

Schachner, M.K. (2019). From equality and inclusion to cultural pluralism: evolution and effects of cultural diversity perspectives in schools.’ European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(1), pp.1-17. Web.

Schildkamp, et al. (2020) ‘Formative assessment: a systematic review of critical teacher prerequisites for classroom practice.’ International Journal of Educational Research, 103, pp.1-16. Web.

Schildkamp, K. (2019) ‘Data-based decision-making for school improvement: research insights and gaps.’ Educational research, 61(3), pp.257-273. Web.

Sindhu, et al. (2019) ‘Aspect-based opinion mining on student’s feedback for faculty teaching performance evaluation.’ IEEE Access, 7, pp.1-13. Web.

Soar, et al. (2019) ‘2019 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations: summary from the basic life support; advanced life support; pediatric life support; neonatal life support; education, implementation, and teams; and first aid task forces.’ Circulation, 140(24), pp.826-880. Web.

Stanley, et al. (2020) ‘Operationalization of Bandura’s social learning theory to guide interprofessional simulation.’ Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 10, pp.10-61. Web.

Watters, A. (2023) Teaching machines: the history of personalized learning. MIT Press.

Westbroek, et al. (2020) ‘A practical approach to assessment for learning and differentiated instruction.’ International Journal of Science Education, 42(6), pp.955-976. Web.

Yan, et al. (2021) ‘A systematic review on factors influencing teachers’ intentions and implementations regarding formative assessment.’ Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 28(3), pp.228-260. Web.