Introduction

Literature Review

Prior research demonstrates that international students encountered many difficulties because of language and cultural barriers, educational and financial difficulties, interpersonal challenges, racial intolerance, loss of social support, estrangement and homesickness (Sherry, Thomas & Chui 2010, p. 34). Language proficiency was the single most important factor that determined the educational success of international students since it did not only affect their ability to succeed by influencing their psychological state of mind but impacts their capacity to interact socially with other students (Olson 2012, p. 27). Valez-McEnvoy (2010, p. 82) reports that language barriers are known to lessen students’ capacity to successfully understand lectures, take notes in class, complete assessments and examinations and engage in productive communication.

For international students, it was obvious that language was not only an instrument of structuring communication but also a noteworthy aspect that positively or negatively influence their educational achievement. Due to these factors, international students with language difficulties often experience stress, which acted as a barrier to successful acculturation (Mettler 1998, p. 100), communication competence (Hallberg 2009, p. 188) and educational progression and success (Nielsen 2005, p. 527). Indeed, available literature demonstrates that not only was it increasingly difficult for students exhibiting language deficiencies to do well in their studies but they often experienced too much arousal due to irrational fear of failing examinations and communicating with others resulting in harm to mind and body (Sanner, Wilson & Samson 2002, p. 28).

From then, it was evident that there was a wide body of knowledge on the perceived consequences of the language barrier problem among international students. However, relatively little was known about the coping strategies adopted by these students to deal with the language barrier problem. More importantly, there still exist gaps in knowledge on the most successful coping strategies that international students could adopt to overcome the challenge presented by the problem (Doron et al. 2009, p. 516).

Research Question

The study investigated the experiences of international students at Flinders University in order to develop a deeper understanding of how they cope with language barriers. The key research question was “What are the coping strategies for international students with language barriers?”

Hypotheses

The study sought to prove or reject the following hypotheses:

- H: Students who cope with language barriers were happy

- H: There was a direct positive correlation between the language barrier and the educational level of students living abroad, and

- H1: There was no direct positive correlation between the language barrier and educational level of students living abroad.

Ethical Implications

The proposed study used human participants and therefore the researcher was not only guaranteed informed consent and confidentiality but also desisted from invading the participants’ privacy and coercing them to participate (Fleischman 2011, p. 8). The researcher also guaranteed that participants were not exposed to harmful activities or deceptive practices that may compromise the integrity of the scientific enterprise (Lambert & Glacken 2011, p. 783).

Flinders University’s social and behavioural research ethics applications were completed before the commencement of this study. During recruitment, important information contained in a standard verbal script (appendix 1) was given to participants to enable them to make the decision to participate or not. A letter of introduction (appendix 2) was given to willing participants not only to provide more information about the study but also to ensure the confidentiality of responses. An information sheet (appendix 3) describing the study, confidentiality, engagement issues and what would be required of participants will be provided. However, a consent form (appendix 4) detailing the rights and freedoms of participants was availed for signing (Krinke, 2002).

Discussion

Main Findings

A five-point Likert-type scale was used to evaluate how international students with language difficulties faired on a number of key issues. On the scale, one represents strongly agreed while five represents strongly disagreed. From the analysis, it is important to note that the significance of the normality test for all the variables is less than 0.05, implying that the data is not normally distributed. Many of the standard deviations for the variables demonstrated that the spread of values in the data set was large implying that the mean score of most variables cannot be taken as representative of the data. It was therefore imperative to use the median and the interquartile range in variables that have a standard deviation of more than one. The descriptive statistics for the issues were presented in table 1 next page.

The presentation below demonstrates that most respondents strongly agreed that 1) they were satisfied with the extent of their intellectual development at the university given the language barriers they experience and 2) they made the right decision by attending this university.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Key Issues facing International Students with Language Barriers

Additionally, most respondents agreed that they could be able to develop a close personal relationship with other students despite the language difficulties (Bas et al. 2005, p. 56). To drive the point home, most respondents also agreed to the point that the language difficulties experienced had a positive influence on their personal growth, attitudes and values and that their classroom interactions with teachers had a positive influence on their personal growth, attitudes and values. These observations proved the hypothesis that students who cope with language barriers were happy (Selvadurai 1998, p. 154).

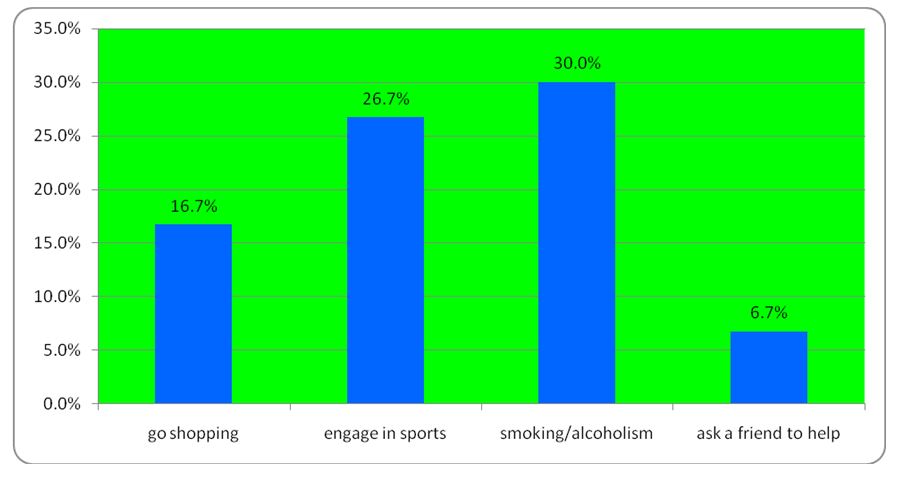

A major finding of the study was that 24 (80%) of the respondents reported suffering from academic stress as a direct consequence of the language barrier problem. However, all respondents reported receiving some form of support from family, friends and colleagues to deal with the academic stress. When asked what coping mechanisms they employed to deal with the stress triggered by the language barrier, almost a third of the respondents (30%) said they smoked or consumed alcohol, while 2 (6.7%) asked for assistance from a friend. The rest of the distribution is demonstrated in the figure below.

References

Akbayrak, B 2000, ‘A comparison of two data collection methods: Interviews and questionnaires’, Journal of Education, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Baric, CI, Satalic, Z, & Lukesic, Z 2003, ‘Nutritive value of meals, dietary habits and nutritive status in Croatian university students according to gender’, International Journal of Food Science Nutrition, vol. 54, no. 6, pp.473-484.

Bas, M, et al. 2005, ‘Determination of dietary habits as a risk factor of cardiovascular heart disease in Turkish adolescents’, European Journal of Nutrition, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 174-182.

Bernard, HR 1999, Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, Sage Publishing Inc., London.

Bono, JE & McNamara, G 2011, ‘From the Editors Publishing In AMJ—Part 2: Research Design’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 54 no. 4, pp. 657-660.

Brevard, PB & Ricketts, CD 1996, ‘Residence of college students affects dietary intake, physical activity, and serum lipid levels’, Journal of American Diet Association, vol. 96, no. 4, pp. 35-38.

Doron, J, Stephan, Y, Boiche, J & Le Scanff, C 2009, ‘Coping with examinations: Exploring relationships between students’ coping strategies, implicit theories of ability, and perceived control’, British Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 79, no. 3, pp. 515-528.

Fleischman, A, et al. 2011, ‘Dealing with long-term social implications of research’, The American Journal of Bioethics, vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 5-9.

Gibbons, C, Dempster, M & Moutray, M 2011, ‘Stress, coping and satisfaction in nursing students’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 621-632.

Hallberg, D 2009, ‘Socioculture and cognitivist perspectives on language and communication barriers in learning’, World Academy of Science Engineering & Technology, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 186-195.

Hiser, J, Nayga, R & Capps, O 1999, ‘An exploratory analysis of familiarity and willingness to use online food shopping services in a local area of Texas’, Journal of Food Distribution Research, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 78-90.

Jones, S, Murphy, F, Edwards, M & James, J 2008, ‘Doing things differently: Advantages and disadvantages of web questionnaires’, Nurse Researcher, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 15-26.

Kafatos, A, Verhagen, H, Moschandreas, J, Apostolaki, I & Van-Westerop, JJ 2000, ‘Mediterranean diet of Crete: foods and nutrient content’, Journal of American Diet Association, vol.100, no.8, pp.1487-1493.

Kremmyda, L, Papadaki, A, Hondros, G, Kapsokefalou, M & Scott, JA 2008, ‘Differentiating between the effect of rapid dietary acculturation and the effect of living away from home for the first time, on the diets of Greek students studying in Glasgow’, Appetite, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 455-463

Krinke, U 2002, Adult nutrition: in nutrition through the life cycle, Thomson Learning, Belmont.

Lambert, V & Glacken, M 2011, ‘Engaging with children in research? Theoretical and practical implications of negotiating informed consent/assent’, Nursing Ethics, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 781-801.

Mann, CJ 2003, ‘Observational research methods-research design II: Cohort, cross-sectional and case control studies’, Emergency Medicine Journal, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 54-60.

Mettler, S 1998, ‘Acculturation, communication, apprehension, and language acquisition’, Community Review, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 97-108.

Michaelidou, N & Dibb, S 2006, ‘Using email questionnaires for research: good practice in tackling non-response’, Journal of Targeting Measurement & Analysis for Marketing, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 289-296.

Nielsen, P 2005, ‘Practice note: An international dimension in practice teaching’, Review of Education, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 525-531.

Olson, MA 2012, ‘English-as-a-second language (ESL) nursing student success: A critical review of literature’, Journal of Cultural Diversity, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 26-32.

Sanner, S, Wilson, AH & Samson, LF 2002, ‘The experiences of international nursing students in a baccalaureate nursing program’, Journal of Professional Nursing, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 206-213.

Schuster, A & Sporn, B 1998, ‘Potential for online grocery shopping in the urban area of Vienna’, Journal of Electronic Market, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1-8.

Selvadurai, R 1998, ‘Problems faced by international students in American colleges and universities’, Community Review, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 153-167.

Sherry, M, Thomas, P & Chui, WH 2010, ‘International students: A vulnerable student population’, Higher Education, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 33-46.

Simpson, J & Cooke, M 2010, ‘Movement and loss: Progression in tertiary education for migrant students’, Language and Education, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 57-73.

Valez-McEnvoy, M 2010, ‘Faculty role in retaining Hispanic nursing students’, Creative Nursing, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 80-83.

Von-Bothmer, MI & Fridlund, B 2005, ‘Gender differences in health habits and in motivation for a healthy lifestyle among Swedish university students’, Nursing & Health Sciences, vol. 7, no.1, pp.107-118

Welford, C, Murphy, K & Casey, D 2012, ‘Demystifying nursing research terminology: Part 2’, Nurse Researcher, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 29-35.

Young, EM & Fors, SW 2001, ‘Factors related to the eating habits of students in grades 9–12’, Journal of School Health, vol.71, no.2, pp.483-488.

Questionnaire

The purpose of this survey is to assess the coping strategies of international students of University who experience language barriers. This questionnaire has two sections: Demographic Information and Survey Proper. It will be appreciated if you could spare at most 30 minutes of your time in order to participate in it. All provided information will be used solely for academic purposes, and your individual responses will be treated with the utmost confidentiality.

Part 1: Demographic Information (Please Check the Appropriate Box)

-

- Age?

- 18-20

- 21-25

- 26-30

- 31-35

- Above 35 years old

- Gender?

- Male

- Female

- Educational Level?

- High School Graduate

- Undergraduate

- Bachelor

- Postgraduate

- Others (please specify): __________________________

- Marital Status?

- Single

- Married

- Engaged

- Divorced

- Separated

- Others (please specify): __________________________

- Citizenship?

- Chinese

- India

- Saudi Arabia

- Belgian

- Colombia

- Greek

- French

- German

- Australian

- Swiss

- Brazilian

- Japanese

- Turkish

- Spanish

- Iranian

- Others (please specify): ______________________

- Languages Fluent in?

- Chinese Mandarin

- Spanish

- English

- Arabic

- Hindi

- Portuguese

- Russian

- Japanese

- German

- Others (please specify): ______________________

- Age?

Part 2: Survey Proper (Please Check the Appropriate Box)

- Using the following 5-point scale, circle the most accurate response.

- Answer the following questions very briefly:

- Do you feel you suffer academic stress given that you experience language barrier?

- Yes

- No

- What coping mechanisms do you employ to relieve yourself from this language barrier situation?

- Go Shopping

- Playing Video Games with Friends

- Engage in Sports

- Go to the Bar/ Partying

- Eating

- Smoking

- Go to the Library

- Ask a friend for help

- Others (pls. Specify ________________________________________)

- Do you get the support of family, friends and colleagues while suffering academic stress?

- Yes

- No

- Are you getting into substances like alcohol, drugs or smoking to cope with this stress? Briefly explain how it distresses you.

- Yes

- No

- Do you feel that the language barrier you experience has a direct effect on your academic performance in this university?

- Yes

- No