Introduction

For the past two decades, school modernization has been a focus area for lawmakers. With shootings against children reaching frightening levels and student assessment resulting in the United States falling behind those of other developed nations, there is widespread consensus that there is a need for change in American institutions. Regardless of the fact that everyone agrees that reform is required; the sorts of changes that should be implemented to improve the productivity and security of schools are a hotly discussed topic. The subject of dress code is frequently at the center of the educational reform campaign as a component of this worldview. Mandatory school uniform supporters argue that wearing them eliminates financial gaps among learners, equalizes the curriculum field of play, lowers harassment, and therefore produces a more effective school climate in which studying becomes more central.

While there is a significant body of information on the issue, professional, reputable scientific papers, systematic reviews that can be duplicated on a broad scale, and generalized, impartial analyses of the subject are scarce. The basic data supplied is mostly dependent on speculation instead of evidence. At the moment, while there is some questionable data pointing to the relative usefulness of dress code-enforced norms, it is not strong enough to justify the widespread deployment of school uniforms. As such, the research was guided by the question: what are the impacts of school uniforms on school safety? The inquiry based on this question is both professionally and academically important. For instance, despite its constraints, professionally, this research will be of relevance to those interested in public safety requirements, as well as those engaged in uniform licensing. Academically, the inquiry will act as a control of school-associated risks, thus increasing academic achievements when such risks are controlled.

This paper is arranged into four major sections: First, the research contains an introduction to the research highlighting the problem statement, scope of research, objective, and the need for future research on the impact of school uniforms on school safety. Second, the next section is a methodology, which covers the procedures taken for performing an inquiry on the impact of school uniforms on school safety. These parts include search strategy, data synthesis, data extraction, and risk of bias. The third section comprises the results of the inquiry and is divided into such subsections as study selection and discussion of the themes underpinned by the thematic analysis. The last section comprised the conclusion and recommendation of the inquiry.

Methods

Search Strategy

According to the PEO concept for this data analysis, students (P) is subjected to the behavior of wearing school uniforms (E), which might jeopardize school safety (O). According to Booth (2016), the PEO framework is required for the examination of qualitative literature evaluation, where P stands for Population, E stands for Exposure, and O stands for Outcome. Databases containing school safety were scanned for peer-reviewed papers in English that had the key phrase “school uniform” in the title, keywords, or summary.

The search period was from 2016 to the present, which was December 2021. Tables 1 and 2 detail the findings. The major data resources for this analysis were from the CINAHL (EBCOhost). According to Wright et al. (2015), the repository is distinctive in its supply of qualitative scientific proof investigations. Furthermore, the PubMed, Ovid, and Scopus directories were employed to give a diverse selection of scientific publications on the subject at issue. As per Putman and Albright (2017), using key terms as a search method using “AND” and “OR” identifies the needed study information, making it easier to discover the necessary scholarly resources.

Data Extraction

To allow the gathering and compilation of evidence pertinent to the study investigation, a data extraction table (see Table 3) was created. All the data was personally collected, synthesized, and processed. Each featured article provided details on the jurisdiction in which the research was conducted, including sample methods (containing sample size, average age, if any, and sex), predictive variables (containing an assessment of dress code policy adopted, if any), actual results, study methodology, and pertinent conclusions.

Data Synthesis

Critical evaluation of source information is necessary to provide optimum epidemiological features and ensure coherence in the integration of fundamental qualitative evaluations. Though research quality was not considered, the use of peer-reviewed papers improved reproducibility, allowing for thematic synthesis. Inductive coding was used for this section to generate descriptive elements, which were then analyzed to generate analytical themes, as illustrated in the table in Appendix B (see Table 4). This was accomplished by clustering related and comparable codes and calculating the impacts of dress code policies on student safety to produce the topics outlined in the overarching thematic analysis.

Possibility of Bias

The current study did not consider unreported research, notably dissertations and theses. The goal of this elimination method was to improve the integrity of the articles. Conversely, as a result of strong results being more likely to go unreported, there is an upsurge in selection bias and inflating of impacts. Therefore, future research studies might use the information therein, noting the presence of such a bias.

Results

Study Selection

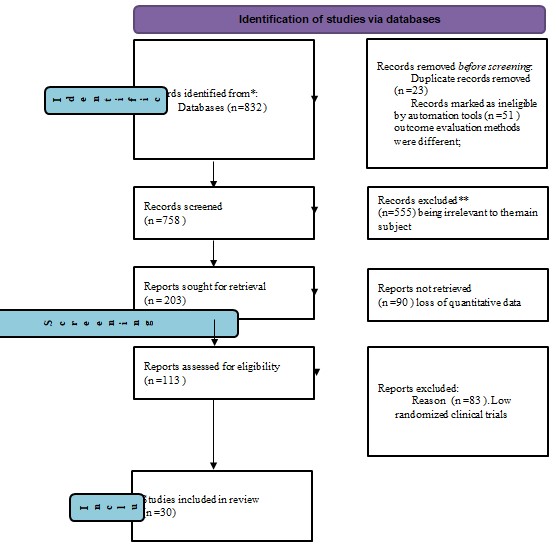

For the analysis, a sample of 30 peer-reviewed journals was retrieved. The search approach generated 758 entries from the CINAHL (EBCOhost) online libraries, PubMed, Ovid resources, and Google Scholar. Upon the elimination of redundancies, 203 articles emerged, of which 90 were removed after reading the full texts because they did not meet the eligibility requirements. The entire texts of the remaining 113 papers were reviewed, and 30 were deemed pertinent. The flow diagram of the articles reviewed is depicted in the diagram in Appendix B (see Figure 1). Thirty-three studies were carried out in the United States, five in the United Kingdom (UK), four in Belgium, three in the Netherlands, two in Turkey and Australia, and one in Bangladesh, Canada, Egypt, Iran, Nigeria, Norway, the Philippines, Spain, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. It should be noted that this research focuses on a range of evidence regarding school dress codes.

Discussion

The information in this part has been organized in accordance with a school safety assessment. First, this section looks at learners’ proximate health, the effects of dress code, and uniform regulation to evaluate if there are any obvious safety consequences of uniform adoption or practice. Second, the justifications for uniform implementation, as well as peripheral elements that impact student behavior, are investigated. This section investigates the broader conceptual and anthropological environment in which uniforms are employed. The mentioned topics are founded on the inductive coding and analytical analyses provided in Figure 2 and Appendix B.

Health

There is a considerably stronger direct relationship between distinctive school clothing, uniform regulations, and safety outcomes. Physical and psycho-social influences on safety can be distinguished, but there is considerable convergence between the two. The physical effects of school clothing include how the garments stimulate physical exercise during the day. The standout questions regarding the issue are whether uniform costumes safeguard the user from recognized climatic risks, whether the garments encourage safety, or whether the outfits are versatile. Blending in (or not) with classmates has psychosocial consequences. There are two key variables measured under “health,” which are described in more detail below.

Physical Health

One influence school dress codes have on bodily health is that they restrict or enable physical activity. Routine physical exercise is encouraged as an element of the WHO’s public health philosophy in all programs and contexts. Agencies throughout the world are attempting to boost regular exercise among children and adolescents to lower childhood obesity rates (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Furthermore, exercising improves learning results and overall well-being (Oakley et al., 2017). As a result, programs that encourage both planned and unplanned physical exercise have a favorable impact on school safety results.

However, it implies that mandatory school garment design and regulation, particularly for females, might be an obstacle to inadvertent exercise. McCarthy et al. (2019) discovered that on sports outfit days, elementary school females were more energetic and fulfilled the government’s prescribed daily training requirements. According to Nathan et al.’s (2021) research on the influence of school costumes on spontaneous physical exercise in 42 public schools in Australia, dress code style may inhibit exercise (assessed by learner self-report and pedometers). In terms of exercise selection, girls conducted considerably more activity during class intervals on sports uniform occasions. Similarly, Okely et al. (2017) revealed that prescribed regular exercise for school-aged students was not being reached, particularly for females, owing to restricted school uniforms. This also limited their activities and presented a clear hurdle to midday play.

Furthermore, in an era of dynamic transportation policies, children frequently cited school dress code designs and a shortage of insulation as a barrier to outdoor sports. Hopkins and Mandic (2017) discovered, for example, that a mandatory school dress code and a scarcity of warm clothing were barriers to riding to school for some female students.The research also revealed that both clothing design and school standard garment policies impeded outdoor transportation among older pupils (Hopkins & Mandic, 2017). There are substantial indicators that standard clothes and regulations about which clothes can be donned have a significant influence on learners’ physical health results, particularly for adolescent girls. While there is evidence that school costumes encourage physical exercise, there is minimal research that suggests school outfits have a cognitive impact on how learners perceive conducting the exercise in a school uniform.

Environmental Hazards

Consistent clothing design and regulatory adoption can safeguard physical health from established ambient health threats. However, school dress codes (whether national or local) do not consistently tackle these risks. In Australia, ozone layer depletion causes excessive UV exposure levels during the hotter seasons. Continuous UV exposure causes damage to the skin and, in the long run, a higher prevalence of melanoma and other cancers in the general populace. On the other hand, Gage et al. (2018) discovered that uniformed institutions had significantly smaller body coverage than non-uniformed institutions but with more neckline coverage due to turtleneck uniforms. As a result, uniformity is a crucial component of zoonotic disease control efforts.

In dengue-endemic nations, school costume styles, the usage of insecticide-treated clothes, and how uniforms are donned have all been intensively researched in connection to dengue standard precautions, particularly how to minimize insecticide from washing out of clothing. While families in these nations favor the adoption of insecticide-treated clothes, parental desire to spend on the attire is tied to the family’s gross pay (Kittayapong et al., 2017). The readiness of the state to finance medicated school garments is also tied to the final budget, regardless of efficacy or prospective health advantage (Kittayapong et al., 2017). It indicates that strong, sustainable apparel design cannot be isolated from sensible policy execution and financial assistance if clothes’ costs are high.

Brimmed caps and sun-safe clothes (covering limbs) can provide additional sunlight shelter without affecting empirical measures of normal somatic temperature. Furthermore, a simulation from Australia shows that marginally longer clothing has a considerable impact on mole structures (McNoe & Reeder, 2019). However, the performance of uniformed clothing (or any garments) for sunlight safety is dependent on regulatory execution. Sunsmart, for example, is an optional corporate policy in New Zealand that safeguards children’s epidermis from UV light damage and sunburn. However, Reeder et al. (2020) revealed, however, that Sunsmart rules were not regularly enforced, even at Sunsmart-accredited institutions. As a result, the Sunsmart initiative on dress code is extremely important in reducing the consequences of melanoma among children.

Psychological Health

School outfits have been shown to be psychosocially beneficial for health. They eliminate competitive dressing and the urge to wear specific outfits. Jones et al. (2016) found that school costumes reduce anxiety and household disagreements about what to wear to school on school days for children with advantaged social levels. The mental and emotional benefits of eliminating competitive clothing are most likely limited to kids with a certain amount of monetary prosperity. According to Pausé (2019), numerous social variables influence regular exercise, and gender-specific sports uniforms improve feelings of security and assurance (Pausé, 2019). In addition, auto-ethnography emphasizes the mental obstacle of an ugly sports outfit. In this scenario, overweight children’s engagement in physical exercise is beneficial in terms of weight loss.

The cognitive benefit of eliminating competitive clothing is most likely limited to kids with a certain amount of monetary prosperity. Aside from the ambiguity of wearers’ sentiments, there is conflicting research on the influence of school dress codes on such abusive behaviors as bullying. Jones et al. (2016) observed a decrease in harassment after the introduction of uniforms. As a result, school costumes seem to be both therapeutic and damaging, based on circumstances, how the learner violates the limits of uniform regulations to blend in, and if the learner is a member of an underrepresented, marginalized minority. In any case, females constitute half of the population, and their physical and mental health appears to be routinely and indiscriminately harmed by school attire design. Overall, regarding the health implications, it appears that any psychosocial gains will only be sustained if additional psychosocial and physical damage to females is avoided.

Social, Cultural, and Political Influences

Because uniforms may have harmful physical and psychosocial safety effects, it is important to study the factors that influence the use of uniforms in schools. Furthermore, authorities should conduct a full investigation into why uniform design has not been addressed despite the presence of documented difficulties in the uniform policy. As a result, it is critical to evaluate the larger context in which the school uniform is utilized.

The Socio-political Environment

Individual safety benefits of uniform are ensconced in the larger school culture, which in turn is impacted by the wider socio-political framework, which is primarily determined by society’s values, as indicated in the figure below in Appendix B (see Figure 2). Uniforms, therefore, reflect the national past, power systems, and societal trends. Over time, the design of uniforms in England has steadily adopted more contemporary and Western ideas (Wallace & Joseph-Salisbury, 2021).

Parents in New Zealand perceive that prices prevent their children from fully participating in typical educational experiences and socializing with their more privileged classmates. According to Gasson et al. (2017), school climate is a “disciplinary technique” that embodies decency, elegance, simplicity, and inoffensiveness. Conformity, on the other hand, involves matching the criteria of an institution and, therefore social, and political culture, overtly in service of an ideal of equality and implicitly in order to sustain the social power dynamics articulated via organizations. Whether or not it is a type of authoritarian attitude, attire is clearly related to wider social ideals.

In certain cultures, the wearing of uniforms is seen as an essential part of achieving a larger social goal. Thus, Baumann and Kriskova (2016) claim that high PISA results correlate with effective classroom management, which is inextricably related to broader cultural ideals. The authors believe that Confucian norms of self-discipline and ceremonial compliance impact practical elements of everyday life in Korea and Japan. According to Baumann and Kriskova (2016), complying with social norms is an essential aspect of becoming a good Confucian; consequently, any consequence for violating uniform standards (a social norm) is expressly and inextricably related to being a decent Confucian.

The uniform’s significance is also derived from cultural and historical viewpoints. According to Martin and Brooks (2020), uniforms in England aim to equalize socioeconomic status and provide social camouflage via useful and reasonably priced apparel. However, this reasoning overlooks broader social power dynamics, and school uniform wearing may be primarily used to achieve another aim. Thus, in certain post-colonial situations, uniforms were seen as a means of transferring values and were viewed as a means of civilizing and promoting a particular ideology. Certain sorts of school uniforms, according to Australian scholars, traditionally signified legitimacy and contentment and encouraged social inclusion. In other words, school uniforms help migrant children (and their families) feel more at home in their new communities.

Some sociocultural reasoning is apparent and these are elements of well-defined public policy actions to influence society. Mujiburrahaman and Muluk (2017), for example, characterized dress code as an aspect of Sharia law application in schools. On the other hand, Moser (2016) adds that it is part of promoting patriotism and culture in Indonesian schools. Furthermore, Draper (2016) outlines how costumes that combine classic and new clothing designs, resources, and production processes are used as part of a heritage revival effort in Thailand. Indeed, school outfits are generally regarded as more impartial than dress standards since everyone wears the same thing, as compared to apparel being judged against a standard. Overall, it seems that uniform usage is often motivated by aims other than health, safety, and values.

Image of the School’s Cultural Community

With respect to location and race, schools are organizational expansions of intersecting societies. Social norms are reflections of cultural and structural regulations. As a result, if a school is known for undesirable social standards such as harassment and disobedience, the costume they wear reflects this. For example, since clothes enhance an organization’s culture inside schools, conveying school ideals to children is represented via school systems as a cultural center. As per Baumann and Krskova (2016), a well-disciplined student population is associated with a specific sort of clothing. Though allegiance is linked to togetherness, which means protection during a crisis or possible danger, unity is jeopardized if the outfit is too costly and restricts other students (Sabic-El-Rayess et al., 2019). Attires, it has been said, send signals to individuals beyond the school setting. According to Alnajdawi (2019), the primary function of uniforms has shifted from mainly resolving poverty or reducing distinctions identifying status and sexuality to predominantly communicating academic standards and the institution’s standing in the education industry.

Human Rights

In combination with the dress code, human rights policies promoting fairness, religious liberty, or gender inequality, as well as safeguarding children’s rights, have been debated. Human rights legislation has been used to assist in reconciling diverse rights and morals in circumstances when there is dispute regarding clothing design or standard uniform policy, yet established norms or social expectations do not offer an alternative. According to Ahrens and Siegel (2019), school uniforms were a federal constitutional issue (infringing on the First Amendment right to free speech), but there are now few constitutional and statutory issues with the same clothing at schools. In practice, the practice of school uniforms illustrates that enforcing many human rights at the same time is difficult.

Gender Equality

Human rights safeguard liberty of gender bias, and standard clothing patterns have a greater influence on females, notably on their physical safety. Importantly, females’ clothes are more costly than boys’ outfits, indicating the existence of a “pink tax” for female-oriented items that fulfill the same purpose as a male version (Mutengi, 2018). Non-inclusive standardized clothing regulations are especially troublesome for gender-nonconforming pupils and have a detrimental impact on them. According to Jones et al. (2016), there is a clear association between the foundation of gender ideology and sexual orientation in schooling and school uniforms. Schools, as per Bragg et al. (2018), provide teaching experiences to foster gender and sexual plurality.

Overall, it seems that adolescents’ proximate social and cultural surroundings are built in such a manner that the concept of gender options is often unavoidable from the standpoint of school uniforms (Bragg et al. (2018). As a result, non-inclusive dress code policies are based on the notion that apparel is an integral component of gender identification (Jones et al., 2016). Furthermore, the suppleness or adaptability of clothing regulations risks weakening both individual and community sexual orientation.

According to the evidence, females face a physical constraint as well as a hefty price tag when wearing uniforms, and policy rarely addresses gender-diverse students.Regarding the overriding right to equitable treatment regardless of gender, this is influenced by social and economic patterns and has a detrimental impact on human rights. As per the examples above, human rights law should enable schools to have similar dress codes for boys and girls, with the cost of uniforms equal so that one sexual identity or group is not disadvantaged.

Religious Liberty

In addition to broad rights to equal treatment, specially protected rights, including religious freedom and the right to non-discrimination based on gender, are at issue while contemplating uniforms. Courts are sometimes challenged to reconcile apparently incompatible rights, such as uniform regulations, with the right to religious freedom. In Kazakhstan, one of the points of the ruling stated that the incorporation of religious symbols into school uniforms is prohibited (Podoprigora, 2018). This decree has sparked outrage among parents who believe that such a restriction breaches their religious freedom. As a result, kids and parents impacted by these regulations often suffer from psychological trauma inside their jurisdictions. Church-based institutions in Kenya are in violation of the comprehensive private school regulations, which include shorts as a dress choice for girls (Lopez & Rugano, 2018). In this issue, there is disagreement about whether religious beliefs should be included in the academic dress code policy (Podoprigora, 2018). As a consequence, the gender-neutral legislation may cause psychological anguish, particularly among students who see it as a moral disadvantage.

Equality and Equity

The human rights concept of equality for all people is crucial in the school dress code. As previously stated, a major historical and contemporary motivation for this outfit is the belief that social concealment improves equity in access to school. Uniform supporters believe that it provides parity and emphasizes the advantages of uniformity that exceed any adverse effects: unity, a feeling of connection (albeit this argument has not been objectively verified), and group identification. In their opinion, reducing visible indicators of class distinctions improves the basic dignity of equitable rights (Woo et al., 2020). As a result, an emphasis on justice in uniform policy avoids the question of who suffers the weight of fairness as “homogeneity.”

Uniforms are a significant financial obstacle to accessing school, especially in poor and middle-income nations. Sabic-el Rayess et al. (2019) employ Mongolia as an illustration, noting that in nations where the extremely poor cannot buy clothes, children do not attend school. Similarly, Cho et al. (2018) discovered that in Kenya, enrolment percentages among the extremely poor are reduced due to school uniform costs. Mutengi (2018) established a statistically significant connection between the cost of school and access to school in Kenya. Furthermore, Green et al. (2019) also mentioned free uniforms as part of assistance and performance bonuses for at-risk children to pursue education. The findings revealed that not giving uniforms lowered student attendance, resulting in a psychological health concern for individuals eager to attend school without causing any damage.

Theoretical Framework

According to research, school safety may either boost or detract from kids’ academic performance and the school’s reputation as a safe space. The atmosphere of an institution determines its safety, which impacts the conduct of its participants. According to Haveman and Wetts (2019), social systems and space requirements as a climate are organizational goals that are assessed by the participants’ impressions. Safety and climate are inherent in the institution, and they are present irrespective of how they are communicated (Haveman and Wetts, 2019). Wearing uniforms should affect safety since it impacts the school setting.

The Hierarchy of Needs model may help people understand the atmosphere of a financial institution, agency, or school. According to McLeod (2020), Maslow investigated organizational motivation variables and the requirements that must be met in order for individuals in an institution to be functional. Maslow defined five needs centered on his revised pyramid model: physiological (clothing), safety (security), social, esteem, and self-actualization (McLeod, 2020). He adapted the idea to companies, postulating that it is the executives’ responsibility to motivate people by meeting their fundamental needs and enabling them to attain self-actualization (as cited in McLeod, 2020). These five requirements are what institutions need in order to be successful. It is the duty of leadership and instructors to collaborate and implement various initiatives that make children feel secure and confident, enabling them to perform to their maximum capacity at school.

The fundamental requirements described by Maslow must also be met by learners, instructors, and school officials. De Bruijn et al. (2021) also recognized that cognitive demands are influenced by the school’s physical qualities such as location, illumination, and temperature. Physical safety demands are met by personal security. Healthy interaction among all managers, instructors, and students promotes social requirements of companionship and tolerance.

Individual achievement in school recognizes and acknowledges self-esteem requirements. Students who feel protected, welcomed by their classmates and instructors, and recognized for their performance appear to have better self-esteem and are encouraged to work hard.

A school’s atmosphere reflects the overall perspective of all shareholders’ norms and ideals. Advocates of the school safety and uniform use hypothesis argue that an institution’s environment, milieu, social structure, and ethos all have an impact on the school’s capacity to govern learners’ conduct (Konold et al., 2018). Supporters argue that when social safety is more organically cohesive and students have a common understanding of ideals and ethics, student results, including school dysfunction; will be better (Konold et al., 2018). Since everyone is wearing the same attire, school uniforms enhance a child’s feeling of connection and belonging.

Conclusion

This research indicates that school uniforms are a significant but underappreciated public safety concern that impacts all learners who are obliged to wear them. As a baseline evaluation, this research explores the theoretical landscape of mandatory school clothing style and regulation within a health promotion paradigm, and it puts data together to demonstrate the safety implications of school dress code use. The review demonstrates that wearing a school uniform is significant, but not for the motives that most strongly consent to it.

First, there is still a widespread idea that wearing a school uniform improves academic performance. There is no data to support this claim—there is no clear correlation between dress and academic ability. Uniforms, on the other hand, lead to a more established classroom climate, which improves learning. Second, some research contends that wearing a uniform might interfere with a positive connection between students and instructors, which is connected to enhanced learning. Third, contrary to popular assumption, uniforms have no scientifically validated influence on increasing a student’s sense of belonging to a school. Notably, there is a general lack of evidence supporting usage, as well as a disparity between what is thought about school outfits and what is validated by actual research.

Nevertheless, any detrimental school safety consequences of uniform apparel choice and regulation are modifiable. The insight provided by this analysis concerning the evidence supporting uniforms’ influence on school safety may serve as a catalyst to ensure that the dress code maintains as secure a working environment as feasible to capitalize on the benefits uniforms bring. Analyzing facts about how school costume and uniform policies affect students’ safety may make it easier to develop a clear understanding of why school uniforms are used to improve user welfare. If the effects of uniforms on school security are obvious, it may be feasible to enhance the user perspective such that clothes are attractive, egalitarian, hygienic, and safe, and that both regulations and costumes allow all learners to study and flourish in contemporary society.

The key drawback of this research is that information is solely gathered from English-language studies primarily centered on the English-speaking world or where papers are accessible in English alone, despite the fact that much of the globe that dresses in uniform is not English-speaking alone. Data that may have been crucial may have been overlooked. Furthermore, the main sources of data for this review are mostly peer-reviewed journals, which provides rigor but excludes the richness of various sources of knowledge. Because this study concentrated on proof of uniform usage rather than the reliability of that information, articles of various sorts were included. Therefore, the research is of particular significance to members of the broader public, who will be properly educated on the facts of what a uniformed school achieves and what can be required to enhance it. Theoretically, dress code design challenges are of appeal to scientists of various demographics with impaired abilities or whose garment options are limited.

As a recommendation, scholars who undertake future analyses of school uniforms will acquire knowledge about how they affect the environment of a school. There are loopholes in current school costume studies. However, evidence on this issue has only been collected after children’s school clothes were implemented. Future studies should explore techniques to study the safety of schools prior to and immediately following uniform implementation. It is just as vital to understanding what the culture would have been like if school costumes were imposed as it is to know what the culture was like thereafter. It is critical to have something to relate to. Therefore, prospective scholars might consider the following: How have school clothes affected school security? What impact did the dress codes have on student safety?

References

Ahrens, D. M., & Siegel, A.M. (2019). Of Dress and Redress: Student dress restrictions in constitutional law and culture. Harvard Civil Rights–Civil Liberties Law Review, 54(1), 49–106.

Alnajdawi, A. M. (2019). Exploring Jordanian children’s perceptions of the characteristics of an ideal school and learning environment. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 10 (4), 201-225. Web.

Andries, F. F. (2021). Dualism in the South Halmahera Government’s Policy on Managing Diversity in the Bacan Sultanate. Humaniora, 33(1), 17-25.

Baumann, C. and Krskova, H. (2016). School discipline, school uniforms and academic performance, International Journal of Educational Management, 30(6), 1003-1029. Web.

Bellino, M. J., & Dryden-Peterson, S. (2019). Inclusion and exclusion within a policy of national integration: refugee education in Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(2), 222-238. Web.

Booth, A. (2016). Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews, 5(74), 1-23. Web.

Bragg, S., Renold, E., Ringrose, J., & Jackson, C. (2018). More than boy, girl, male, female: Exploring young people’s views on gender diversity within and beyond school contexts. Sex Education, 18(4), 420–434. Web.

Cho, H., Mbai, I., Luseno, W.K., Hobbs, M., Halpern, C., & Hallfors, D.D. (2018). School support as structural HIV prevention for adolescent orphans in western Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health. 62(1), 44-51. Web.

de Bruijn, A. G., Mombarg, R., & Timmermans, A. C. (2021). The importance of satisfying children’s basic psychological needs in primary school physical education for PE-motivation, and its relations with fundamental motor and PE-related skills. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1-18. Web.

Draper, J. (2016). The design and manufacture of municipal and school uniforms for a northeastern Thai municipality. Sojourn, 31(1), 358–375.

Gage, R., Leung, W., Stanley, J., Reeder, A., Mackay, C., Smith, M., Barr, M., Chambers, T., & Signal, L. (2018). Sun protection among New Zealand primary school children. Health Education & Behavior, 45(5), 800–807. Web.

Gasson, N. R., Pratt, K., Smith, J. K., & Calder, J. E. (2017). The impact of cost on children’s participation in school-based experiences: parents’ perceptions. New Zealand journal of educational studies, 52(1), 123–142. Web.

Gerdin, G., Philpot, R.A., Larsson, L., Schenker, K., Linner, S., Moen, K.M., Westlie, K., Smith, W., & Legge, M. (2019). Researching social justice and health (in) equality across different school health and physical education contexts in Sweden, Norway and New Zealand. European Physical Education Review, 25(1), 273-290. Web.

Green EP, Cho H, Gallis J, Puffer ES. (2019).The impact of school support on depression among adolescent orphans: A cluster-randomized trial in Kenya. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(1):54-62. Web.

Haveman, H. A., & Wetts, R. (2019). Contemporary organizational theory: The demographic, relational, and cultural perspectives. Sociology Compass, 13(3), 1-20. Web.

Hopkins, D., & Mandic, S. (2017). Perceptions of cycling among high school students and their parents. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 11(5), 342-356. Web.

Jones, T., Smith, E., Ward, R., Dixon, J, Hillier, L., & Mitchell, A. (2016). School experiences of transgender and gender diverse students in Australia. Sex Education, 16(2), 156–171. Web.

Kittayapong. P., Olanratmanee. P., Maskhao. P., Byass. P., Logan. J., Tozan.Y, Louis.V., Gubler. D.J., & Wilder-Smith.A. (2017). Mitigating diseases transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes: A Cluster-Randomised Trial of Permethrin-Impregnated School Uniforms. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(1), 1-12. Web.

Konold, T., Cornell, D., Jia, Y., & Malone, M. (2018). School climate, student engagement, and academic achievement: A latent variable, multilevel multi-informant examination. Aera Open, 4(4), 1-17. Web.

Li, P. (2021). Designing an elementary school uniform with functions of fit, comfort, and road safety. The Journal of Design, Creative Process & the Fashion Industry, 11 (2), 222-243. Web.

Lopez, A. E., & Rugano, P. (2018). Educational leadership in post-colonial contexts: What can we learn from the experiences of three female principals in Kenyan secondary schools?. Education Sciences, 8(3), 1-15. Web.

Martin, J. L., & Brooks, J. N. (2020). Loc’d and faded yoga pants, and spaghetti straps: discrimination in dress codes and school push out. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 16(19), 1-19. Web.

McCarthy, N., Nathan, N., Hope, K., Sutherland, R., & Hodder, R. (2019). Australian Secondary school student’s attitudes to changing from traditional school uniforms to sports uniforms. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 22, (2), 94-S95. Web.

McLeod , S. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. Web.

McNoe, B. M., & Reeder, A. I. (2019). Sun protection policies and practices in New Zealand primary schools. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 132(1497), 46-54.

Moser, S. (2016). Educating the nation: Shaping student-citizens in Indonesian schools. Children’s Geographies, 14(3), 247–262. Web.

Mujiburrahman, M.S., & Muluk. S. (2017). School culture transformation post islamic law implementation in Aceh. Advanced Science Letters, 23(3), 1-5. Web.

Mutengi, R. (2018). Demand for education in Kenya: The effect of school uniform cost on access to secondary education. European Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(2), 34–45. Web.

Nathan, N., McCarthy, N., Hope, K., Sutherland, R., Lecathelinais, C., Hall, A., & Wolfenden, L. (2021). The impact of school uniforms on primary school student’s physical activity at school: outcomes of a cluster randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 1-9. Web.

Okely, A. D., Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., Cotton, W., Peralta, L., Miller, J., Batterham, M., & Janssen, X. (2017). Promoting physical activity among adolescent girls: the girls in a sports group randomized trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 1-13. Web.

Pausé C. (2019). (Can we) get together? Fat kids and physical education. Journal of Health Education, 78(6), 662–669. Web.

Podoprigora, R. (2018). School and religion in Kazakhstan: No choice for believers. Journal of School Choice, 12(4), 588-604. Web.

Putman, W. H., & Albright, J. (2017). Legal research, analysis, and writing (4th ed.). Cengage.

Reeder. A.I., Mcnoe. B., Petersen. A.L. (2020). SunSmart accreditation and use of a professional policy drafting service: Both positively and independently associated with high sun protective hat scores derived from primary school policies. Journal of Skin Cancer, 2020(1), 1-7. Web.

Sabic-El-Rayess, A., Mansur, N., Batkhuyag, B., & Otgonlkhagva, S. (2020). School uniform policy’s adverse impact on equity and access to schooling. Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(8), 1–18. Web.

Sommer, M., Figueroa, C., Kwauk, C., Jones, M., & Fyles, N. (2017). Attention to menstrual hygiene management in schools: An analysis of education policy documents in low-and middle-income countries. International Journal of Educational Development, 57(1), 73-82. Web.

Wallace, D., & Joseph-Salisbury, R. (2021). How, still, is the black Caribbean child made educationally subnormal in the English school system?. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 1-27.

Werner, S., & Hochman, Y. (2017). Social inclusion of individuals with intellectual disabilities in the military. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 65(1), 103-113.

World Health Organization. (2016). Ending childhood obesity. Web.

Wright, K., Golder, S., & Lewis-Light, K. (2015). What value is the CINAHL database when searching for systematic reviews of qualitative studies?. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1-8. Web.

Zuilkowski, S.S., Samanhudi, U., & Indriana, I. (2019). There is no free education nowadays’: youth explanations for school dropout in Indonesia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 49(1):16–29. Web.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

The diagram below explores the PRISMA review for the identification of studies via databases.

Table 4: Thematic analysis of themes and subthemes derived from inductive coding