Executive Summary

During the past two decades there have been dramatic increases in the number of women who are pursuing managerial and professional careers. The majority of the women have undertaken university education to prepare themselves for careers. Research evidence suggests that these female graduates enter the workforce at levels comparable to their male colleagues and with similar credentials and expectations; however, they are not entering the ranks of senior management at comparable rates. Women are gaining the necessary experience and pay but they still encounter a “glass ceiling”. The relative failure of these women to move into ranks of senior management, in both private and public sector organizations in all developed countries has been well researched and documented. However, Women are making inroads in some executive ranks.

In others, their progress has been slow. Organizations seem to be doing a good job at recruiting and hiring capable women, but they appear to have difficulty in developing and retaining managerial women and advancing them into ranks of senior management. This paper discusses presents career opportunities available beyond the mainstream organizations and the possible challenges encountered by female bachelors’ graduates. What is clear is that the range of jobs that will be available to the up-and-coming Swiss universities of applied sciences female Bachelor of Business graduates is that they will be required to be flexible, innovative, and well-educated. This is exactly the kind of worker that a background in business will produce. Much of Switzerland’s economic future will be based, directly, on high-tech production and the marketing and distribution of such products. This arises in part from tradition. As a small country without a wealth of natural resources, Switzerland has had to rely on intelligence, a cooperative attitude, and innovation to survive in the past.

As the world grows smaller and more competitive, the country will continue to rely on these qualities, qualities that the business student – whether male or female – will be able to provide. However, the current environment for women in management reflects progress, but not enough. Glass ceilings, glass walls, prejudices and discrimination remain. There are many changes that must be made for women to see additional strides in career advancement. There are a number of practical ways organizations can adopt to ensure women are as likely as men to access and benefit from training and career development opportunities. Equal opportunity and diversity change requires a degree of commitment. Applying four key principles can help ensure change does happen. The four principles or P’s, people, policy, provision, and positive encouragement. The truth is that women do not have to do what is expected of them. They can take risks, challenge the status quo, and create new visions of how to live in the world by going out of the comfort zone. The responsibilities in management should be looked at through the glasses of a challenge and not as an obstacle. Using this positive approach, all challenges are opportunities. Glass ceiling or glass walls can be shattered by applying the right attitude. The attitude of achievement and commitment to reach the goals female graduates will set for themselves.

Glossary

Table 1 – Glossary.

Introduction

Current situation

During the past two decades there have been dramatic increases in the number of women who are pursuing managerial and professional careers.1 “Most of these women have prepared themselves for careers by undertaking university education and they now comprise almost half of the graduates of professional schools such as accounting, business and law”.2

According to Davidson M. J. and Burke R. J. in their book Women in Management: Current research issues, “research evidence suggests that these graduates enter the workforce at levels comparable to their male colleagues and with similar credentials and expectations, but it seems that women’s and men’s corporate experience and career paths begin to diverge soon after that point”.3

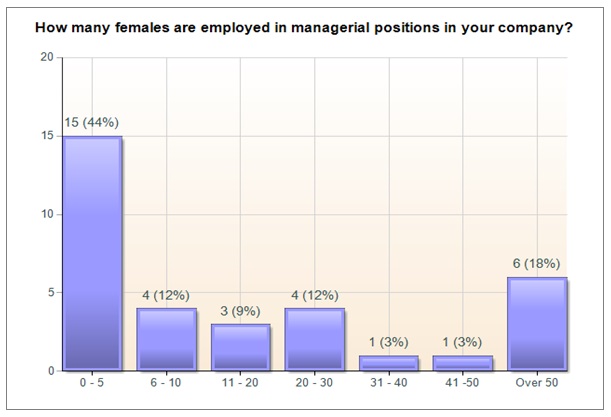

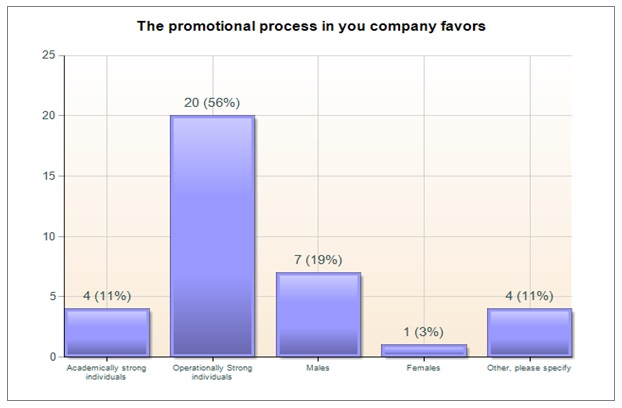

It is evident that although managerial and professional women are at least as well educated and trained as their male counterparts and are being hired by organizations in approximately equal numbers, they are not entering the ranks of senior management at comparable rates. The supply of qualified women for these management jobs has increased steadily as more women accumulate experience and education. Women are more likely to occupy managerial jobs in fields in which women are employed in non-management jobs. Women in executive and managerial jobs are likely to be found in services, insurance, and real estate industries. They are less likely to be found in manufacturing, construction, transportation, and public utilities.4

Women are gaining the necessary experience and paying but they still encounter a “glass ceiling”.5 The relative failure of these women to move into ranks of senior management, in both private- and public sector organizations in all developed countries, has been well documented.6

Why should organizations be interested in developing and utilizing the talents of women? Schwartz7 summarizes reasons why supporting the career aspirations of talented and successful managerial women makes good business sense. These include obtaining the best people for leadership positions, giving the chief executive officer (CEO) experience in working with capable women, providing female role models for younger high-potential women, ensuring that companies’ opportunities for women will be noticed by both women graduates in recruiting and women customers and guaranteeing that all ranks of management will be filled with strong executives. The recruitment, hiring and development of managerial women are increasingly seen as a bottom-line issue related to corporate success.8

Women are making inroads in some executive ranks. In others, their progress has been slow. Organizations seem to be doing a good job at recruiting and hiring capable women, but they appear to have difficulty in developing and retaining managerial women and advancing them into ranks of senior management. Most of the women in senior management are in staff positions without direct line responsibility. This indicates the existence of not only the glass ceiling, but also glass walls. The lack of comparable earnings is magnified by the fact that benefits are tied to salary, extending women’s disadvantages to such benefits as health care and retirement. 9

Three major hypotheses have been offered to explain why these barriers have kept women from senior levels of organizations10

The first builds on ways in which women are different from men and concludes that these deficiencies in women are responsible for their lack of career progress. This hypothesis suggests that women’s characteristics, such as attitudes, behaviours, traits and socialization handicap them in particular ways. It also suggests that women may lack the education and job training necessary to qualify for managerial and professional jobs. However, research support for this explanation is limited.11 Almost all the evidence shows little or no difference in the traits, abilities, education and motivation of managerial and professional women and men.12

A second hypothesis builds on notions of bias and discrimination by the majority toward the minority. It suggests that managerial and professional women are held back as a result of bias toward, and stereotypes, of women. The dynamics of this situation are well explained by Kanter (1977) in Men and Women of the Corporation.13 Such bias or discrimination is either sanctioned by the labour market or rewarded by organizations despite the level of job performance of women. In addition, there is a widespread agreement that the good manager is seen as male or masculine.14 Thus there is some research support for this hypothesis.15

The third hypothesis emphasizes structural and systematic discrimination as revealed in organizational policies and practices which affect the treatment of women and which limit their advancement.16 These policies and practices include women’s lack of opportunity and power in organizations, the existing sex ratio of groups in organizations, tokenism, lack of mentors and sponsors, and denial of access to challenging assignments. This hypothesis has also received empirical support. In attempting to identify specific reasons for women’s lack of advancement, it is important to remember that managerial and professional women live and work in a larger society that is patriarchal, a society in which men have historically had greater access to power, privilege and wealth than women. The mechanisms by which this has occurred and is perpetuated are the subject of feminist theory and research.17

Cultural perspective

From a cultural feminist perspective, women value intimacy and develop an ethic of care for those with whom they are connected. Cultural feminism describes the potential for nurturing as a core element of the female experience and psychology18

The model of the successful manager in our culture is a masculine one. As McGregor wrote in his book The Professional Manager, “The good manager is aggressive, competitive, firm, just. He is not feminine nor soft or yielding or dependent or intuitive in the womanly sense”19. This statement is also supported by Rizzo, A. and Mendez, C. (1990), in their book, The Integration of Women in Management: A Guide for Human Resources and Management Development Specialists where they state that, “The very expression of emotion is widely viewed as a feminine weakness that would interfere with effective business processes.20 Yet the fact is that all these emotions are part of the human nature of men and women alike”.

As stated in an article by Syed, J., and Murray, P. A., “Evidence suggests that feminine values are usually associated with nurturing while masculine values are usually associated with achievement”.21 For example, Hofstede’s (1980)22 research identified similarities or differences – on five cultural dimensions – in the underlying value dimensions of employees. Although Hofstede’s work has been criticized on the grounds that each nation has its own internal diversity, Hofstede (1991)23 acknowledges that almost every culture and individual can be located on a continuum between the two extremes of cultural dimension. The article by Syed, J., and Murray, P. A., adds that “one of these dimensions is related to masculine and feminine values (also known as achievement/nurturing dimension), which describes the extent to which values such as assertiveness, performance, success, and competition hold sway over tenderness, quality of life, and warm personal relationships. Within the context of standardized organizational practices, masculine values are generally more dominant”. Such perspective is also shared by other scholars, such as Claes (1991)24 and Trinidad and Normore (2005)25, who notes that masculine characteristics demonstrate the ‘‘normal’’ dominant or assertive aspects of behavior and downplay the team and cooperative behaviors more readily associated with feminine qualities.

Cultural dimensions for Switzerland

Geert Hofstede has identified the following cultural dimensions for Switzerland. “Geert Hofstede ranked Masculinity (MAS) as the highest dimension for Switzerland”. 26

The MAS index indicates a higher polarization between the values of Swiss men and women which implies a strong gender differentiation where the male population is competitive and assertive in comparison to the female population. The second highest is Individualism (IDV) which indicates that the Swiss population is individualistic in nature versus collectivist. Switzerland’s lowest Dimension according to Hofstede is Power Distance (PDI) which indicates that the Swiss population has a relatively equal distribution of power across the population’s societal structure. The third highest Hofstede Dimension is Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) which reflects the society’s level of tolerance for uncertainty. A population which has a high UAI index will institute strict rules, laws, policies, and regulations to reduce uncertainty within the population. A low UAI value as is the case of Switzerland denotes that the population has a tendency towards greater tolerance of different points of view.27

Gender equality from a Swiss statistical perspective

The principle of gender equality has been established in the Swiss Federal Constitution since 1981. The purpose of this legislation is to ensure equality, in particular within the family, education and working life. This also includes the right to the same pay for the same job. The Federal Office for Gender Equality (FOGE) was established in 1988. The equality law, which forbids in particular every form of discrimination in the area of work, has been statutory since July 1996. At a legal level, much has been achieved. Equality needs to be statutory as well as a reality in everyday life. Despite progress, actual equality has not yet been achieved in many areas of life. Pay equality for example has not yet been realised and the division of paid and unpaid work is still characterised by gender differences.28

Education

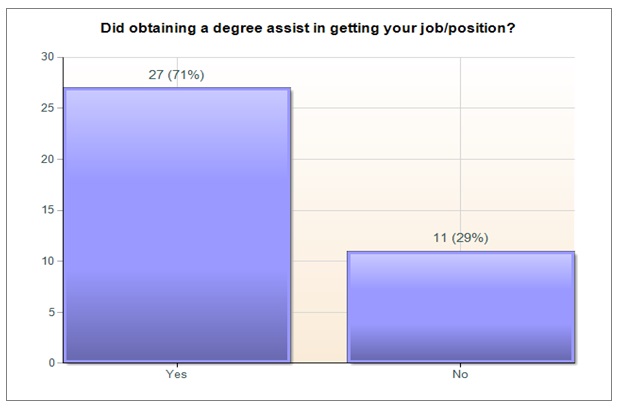

Education is one of the most important means by which gender equality can be achieved. People with a good education usually have more opportunities to shape their working world and environment and can cope more easily with new challenges in family, profession and politics. Furthermore, people with a better education usually have better paid jobs. 29

Differences in education

The proportion of women aged between 25 and 64 years in Switzerland with no post-compulsory education qualification is much higher than that of men of the same age. The gender difference is particularly great at tertiary level. However since 1999, a tendency towards higher levels of education for both men and women can be observed. At university level, the number of graduates is continually increasing, in particular for women, and the gap between men and women is getting smaller. The proportion of women with a higher vocational qualification has also increased slightly. 30

Situation analysis

A World of Possibilities within a Single Country – Switzerland

Given the state of the world economy after the recent financial crisis, current UAS students along with recent graduates may feel that they have few options for success. But while certainly the potential field of opportunities is much more limited now than it was before this recession, there remains a range of possible careers for students with the right background, education, and training. Among those who should find themselves well prepared to enter the work place are UAS bachelors’ graduates. Opportunities for women are somewhat more limited than for men, not because women business students are less well trained but because there are still some reservations in certain firms about hiring women, especially for managerial positions.

UAS bachelors’ graduates who have pursued an undergraduate degree in business should have a wide range of options before them, from working in banking to seeking a job in the IT field, working in the entertainment industry or even the agricultural sector. Other positions open for graduates with a business degree include positions in insurance and consulting, public administration, and working with NGOs. This paper will examine the range of possibilities that are open to bachelor business of administration graduates.

Many of the opportunities available to graduates with business degrees arise from the specific skills that they obtain in their courses of study while others arise from the general business conditions and opportunities in the country. These two are related in a variety of ways since many of the values that influence the culture at large are present in programs of business study throughout the country. Before looking at the specific advantages that Bachelor of Business Administration graduates enjoy, an overview of the climate for business in Switzerland as a whole is of importance. Swiss officials as well as business leaders cite a number of different factors that combine to create a highly favourable arena for both established companies and start-ups, for senior managers as well as for the newest of workers.

Overall Business Climate

Switzerland generally ranks at the top of lists compiled by both government and private-sector groups for overall favourable business climates in the world for a number of reasons. The following statement from DEWS (Development Economic Western Switzerland, an international agency that combines the resources of several Swiss cantons) describes the overall business environment in the following way:

“Numerous criteria contribute to the business climate and competitiveness of a country. Some principal criteria are, a stable legal and political environment, as well as a flexible and resilient economic structure topped with a strong traditional and technological infrastructure, and investment in education. Switzerland has consistently been ranked among the highest nations in the world due to its favorable economic conditions which have been in existence for many years”.31

Chief among these advantages is a well-educated work force. Many of these workers are Swiss citizens who attend Swiss colleges and business schools while others are foreign workers who come to Switzerland to be trained and educated and others still who complete their education before coming to the country. Both male and female graduates are welcome into the workforce, which favours Swiss citizens over foreign workers. Given that there tends to be more men among the foreign workers, women who are Swiss citizens will have an advantage in many cases.

While Switzerland places some restrictions on foreigners that other European nations do not, it does welcome many skilled workers to the nation. While not as open to foreign workers as other Western European nations, Switzerland should not be seen as being opposed to welcoming foreign workers. Thus, individuals who are citizens of other nations who are considering becoming educated in Switzerland in business should not be discouraged from doing so since the overall business climate in Switzerland is so strong in so many different sectors. A growing economy favours all workers and especially those workers (including women as well as foreign workers) who have not reached parity in the workplace before.

DEWS list some of the specific strengths of the Swiss business climate for all types of workers.32

Senior managers’ international experience

This fact can be especially helpful to bachelor graduates who will be appreciated by companies for their specialized business training and who will in turn be able to profit from the experience of having senior managers at a vulnerable point in their careers. This does have the disadvantage to women those senior managers may be somewhat less likely to hire women.

Well developed knowledge transfer

Switzerland is the site of many high-tech companies that rely heavily on innovation. However, even the most cutting-edge of firms can be severely limited, and even crippled, if it gets caught in a cycle of reinventing the wheel – of whatever type is present in its industry. Thus, a well-established, fair, and efficient system of knowledge transfer benefits the business world of a country as a whole, which is turn can be especially beneficial to younger workers who bring in their own innovations as well as their need to be guided by established protocols in their field.

Worker motivation

Swiss workers consistently score as among the most productive in the world in large measure because of their strong motivation to help themselves as well as their companies at the same time. Swiss universities of applied sciences help to inculcate a high level of motivation in their students, and so students who graduate from these schools are likely to be highly sought after by a wide range of businesses.

Readily available finance skills

Swiss businesses, no matter what particular field they may be in, are extremely likely to be able to benefit from the nation’s long tradition of a high efficient banking system. This allows for an efficient system of capitalization of firms (whether established or start-up), which in turn leads to greater opportunities for new workers. Given that most Swiss universities of applied sciences will have provided important training in financial systems to their graduates, these workers will be looked on favourably by potential employers who are looking for workers who have a range of skills, including financial savvy along with general business skills.

Business environment attracts skilled foreign workers

While the Swiss work force is more homogeneous in terms of nationality than a number of other European nations, it is becoming increasingly a host to a multi-cultural work force. Swiss universities of applied sciences alumni who have been trained in being able to communicate and cooperate with co-workers from different countries and cultures will be considered to be highly qualified candidates for jobs in a range of professions.

Productive labour relations

Workers’ rights are guaranteed under a nested set of regulations and laws that exist from the federal to the cantonal to the communal level. These laws are very similar to those in other industrial nations and include provisions such as the establishment of a minimum wage, workplace safety, and the protection of under-age workers. “7 percent of the Swiss workforce is unionized meaning that they have a low level of collective representation”.33 This low level of unionization reflects both the lack of a strong history of labour organization in the country and its cantons and the fact that Swiss workers are very well paid:

Employees in Zurich and Geneva not only take-home top dollar, they can buy the most with their earnings. “There is no comparison to any other international city in terms of their purchasing”.34

Fortune 500 companies

The presence of a number of large, well-funded, and well-established companies in the country allows for greater opportunities for new graduates. Larger companies are generally more likely than start-ups or very small companies to need workers with technical expertise as well as general business knowledge and skills. As new graduates are likely to have the latter and less likely to have the former, the presence of so many Fortune 500 companies is good for new graduates. Fortune 500 companies are generally welcoming of women graduates.35

Each of these factors has a trickle-down effect – or perhaps a synergistic effect. Each of these strengths in the business environment contributes to the others so that the cumulative effect is far greater in terms of offering business opportunities to business graduates than would be the case if the factors were simply added together. The need for many new workers will tend to help women enter fields where they have been historically under-represented.

While this synergy of many different factors is useful for workers at all stages of their careers, it may be that it is especially helpful to Bachelor of Business Administration graduates. Highly skilled and qualified senior workers are likely to have more opportunities open to them than are younger workers and so are likely to suffer less during economic downturns. Younger workers, especially those just finishing their undergraduate work, will fare better in an environment that has a wide range of opportunities and an overall good business climate. In fact, this may be the only kind of business environment in which new graduates will reliably be able to find jobs that match their training and ambitions.

The strength of the Swiss business climate arises from the nation’s traditional force in the banking and financial industries as well as the newer (but still established) science, medical, and technology sectors. The country’s business opportunities are also in general strengthened by the fact that the workforce is generally well educated in both business and management skills as well as in technical fields such as pharmaceutical research, software design, and engineering.

It is also helpful to the overall business sector and to new workers in particular that the business world in Switzerland has access to the full range of markets in Europe. (Although the fact that Switzerland has not yet joined – and shows little interest in joining – the European Union does limit its access to the markets of other European nations in some measure). Finally – and this is of course no small benefit – the nation is extremely stable politically and culturally, allowing businesses to make plans for the future with a sense of security that the current conditions will remain in effect (to the extent that such a sense of predictability and security can ever exist). The following summarizes the overall stability of the country: “Studies on personal security and prosperity, social coherence and political stability have shown that Switzerland regularly leads all international comparisons in this regard.”36

The business climate in Switzerland – and thus in large measure the opportunities for those receiving bachelors’ degrees in business – are being increasingly helped by a lowering of corporate tax rates in Switzerland. Taxes in the nation are higher than in a number of other countries; however, Switzerland’s tax rate may be compensated for a number of businesses by the presence of such a well-educated work force along with stable and well-developed technological, educational, and financial infrastructure.37

The following provides an overview of the tax situation (as of 2008) in Switzerland. The federal government’s (as well as the cantonal governments’) decision to move in the direction of lower corporate taxes must be seen as a sign that the country is dedicated to improving the climate for business. Likewise, the fact that taxes remain at a relatively high rate is indicative (although in a less direct way) of the country’s dedication to business: By maintaining a healthy tax base, Switzerland is ensuring the long-term conditions that help businesses develop and prosper, something that would not be possible if taxes were slashed. This tax structure allows for numerous start-ups, which may be more welcoming of women into professions than are more established companies. The current strategy (as summarized below) balances short-term and long-term business interests and so opportunities for business program graduates:

According to a report by Stefan Mathys, head of public relations at KPMG in Switzerland, “The international comparison of corporate tax rates in 2008 again showed Switzerland significantly improving its position with the median rate for tax on profit (the average of all 26 cantons) went from20.6 per cent in 2007, to 19.2 per cent, a reduction of 1.4 percentage points…this shows a significant downward trend, sinking to between 12.7 and 24.2 per cent, with the two cantons with the lowest rate – Obwalden and Appenzell-Ausserrhoden, both at 12.7 per cent – almost catching up with Ireland, which has the lowest rate in Western Europe (12.5 per cent)”.38

Objectives, scope, and limitations of topic

Objectives

The research objective follows from the background of the study in the topic. It consists of one primary objective, which describes the overall purpose of this thesis and three related secondary objectives, which explain in more detail how the primary objective is to be achieved.

The primary objective of this thesis is to contribute to the understanding of the career opportunities and challenges in management faced by female bachelors’ graduates of UAS in Switzerland.

The secondary objectives are:

- To provide a theoretical contribution: a framework for understanding the career opportunities and challenges in management faced by female bachelors’ graduates.

- To provide a practical contribution: validated in a survey of Alumni female bachelors’ graduates from Universities of Applied Sciences in Switzerland (FHAlumni)

- To derive implications for theory and practice: based on the theoretical and practical studies, implications for the future of female bachelor’s graduate will be derived.

Definitions of key concepts

Management

Management is a process designed to achieve an organization’s objectives by using its resources effectively and efficiently in a changing environment. Effectively means having the intended result; efficiently means accomplishing the objectives with a minimum of resources. Managers are those individuals in organizations who make decisions about the use of resources and who are concerned with planning, organizing, staffing, directing and controlling the organizations activities to reach its objectives.39

Levels of management

Many organizations have multiple levels of management – top management, middle management and first line or supervisory management. These levels form a pyramid, as shown in figure 1. As the pyramid shape implies, there are generally more middle managers, than top managers, and still more first-line managers. Manager’s at all three levels perform five management functions, but the amount of time they spend on each function varies as shown in figure 2, which shows the importance of Management functions to managers in each level.40

Business Administration

Business Administration is the study or practice of planning, organizing and running a business.

Universities of Applied Sciences

There are around sixty colleges of higher education in Switzerland which are grouped into eight higher education regions and which together offer around two hundred courses. These are demanding, practice-oriented training and further education courses in engineering, technology, economics, arts and design, healthcare, social work, music and plastic (responsibility of the federal government) and teacher education (responsibility of the cantons).41

Federal Administration’s “Equal Opportunity at Universities of Applied Sciences” Program

The creation of the universities of applied sciences in the past decade led to a new type of university that in a brief time has become firmly established as part of Switzerland’s educational system. “The universities of applied sciences offer practical university-level education and training and are in great demand with both students and employers”.42 The creation of UAS increased the vocational training level as they create a platform for professionals to continue their studies to university level. UAS enhance innovation in their students and knowledge transfer especially for the part time studies which require the students to work at least eighty percent.

“The universities of applied sciences are performing the role of bridging which links science, the economy and society by using the innovation process. The federal government and the cantons co-operate in steering the system of the universities of applied sciences through their commitment in maintaining the high quality of teaching and research at the universities of applied sciences and to providing the best conditions for further development of the system”.

The challenges facing UAS at the present time are among others the adaption to the Bologna system which helps the UAS’s to be comparable to the international higher education standards and also helps the mobility of those graduating in Switzerland. This is possible since the courses offered at UAS are in various fields including technology, social work and arts, economics as well as health and design to name a few.43

Under-representation of women at universities of applied sciences (UAS).

The Confederation’s main objective (among others), for the UAS domain is to raise awareness of gender equality issues. It has therefore established two main lines of action:

- Including the gender equality principle as a quality criteria in its strategy while establishing specific implementation programs at the same time;

- Increasing the number of female students, professors or researchers at UAS.

The Federal Office of Professional Education and Technology (OPET) have commissioned an action plan along this line.44

Federal program

In the two previous budgetary periods (2000-2003 and 2004-2007) of the Federal Administration’s “Equal Opportunity at Universities of Applied Sciences” Program, OPET developed measures to promote equal opportunities between men and women while nevertheless giving UAS room to test and develop their own equal opportunity measures and project. The federal government should continue the programs in order to ensure gender representation at all levels of education and training and also to continue development of female competencies. “Greater responsibility will be given to the universities of applied sciences where they will be required to implement programs which integrate the equal opportunity principle”. 45

The Federal Council’s Action plan

The Federal Council proposed an action plan to ensure equal representation of students (men and women) as well as teaching staff, professors by the creation of the Promotion of Education, Research and Innovation for 2008-2011. “Students and decision makers should be made aware of gender related issues in an effort have a lasting effect through teaching, research and management. The establishment of a gender equality monitoring system will help to guide the process”.46

Conference of the Swiss Universities of Applied Sciences (KFH)

The Conference of UAS (KFH) encompasses the rectors of the eight universities of applied sciences which are acknowledged by the Swiss Confederation which was established in 1999 which presents UAS interests to the Confederation, the cantons and other institutions in charge of education and research policy as well as the public in general.

The KFH was recognized as an association in July 2001 KFH was recognised as an association and has a general secretariat since May 2002. The directors of the Swiss universities of applied sciences are the member of the association which is headed by a committee of three members elects the members of the special commissions as well as the delegates.47

The eight universities of applied sciences are: Berner Fachhochschule BFH in Bern, Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz FHWZ in Brugg, Fachhochschule Ostschweiz FHO in St. Gallen, Hochschule Luzern HSLU in Luzern, Haute Ecole Spécialisé de Suisse occidentale HES-SO in Delémont, Fachhochschule Kalaidos FH KAL in Zurich, Scuola universitaria professionale della Svizzera italiana SUPSI in Manno and Zürcher Fachhochschule ZFH in Zurich.48

Scope and limitations

Although the Association of Graduates – FHAlumni was used as a means to addressing the scope of this broad topic due to the availability of guaranteed email contacts, this created a limitation on the fact that not all female bachelors’ graduates are registered with the association.

While Switzerland has eight Universities of Applied Sciences, it needs to be emphasized that the results can only be generalized for female bachelors’ graduates in Switzerland who participated in the survey. It is therefore recommended that follow-up studies covering the whole population sample of female bachelors’ graduates be done in order to establish more reliable and representative results. This means that a broader scope is needed as the limitations are based on the number of respondents to the survey and how the answers may not represent the broad spectrum of those bachelors’ graduates in different practices or who are not members of the FHAlumni.

Methodical approach

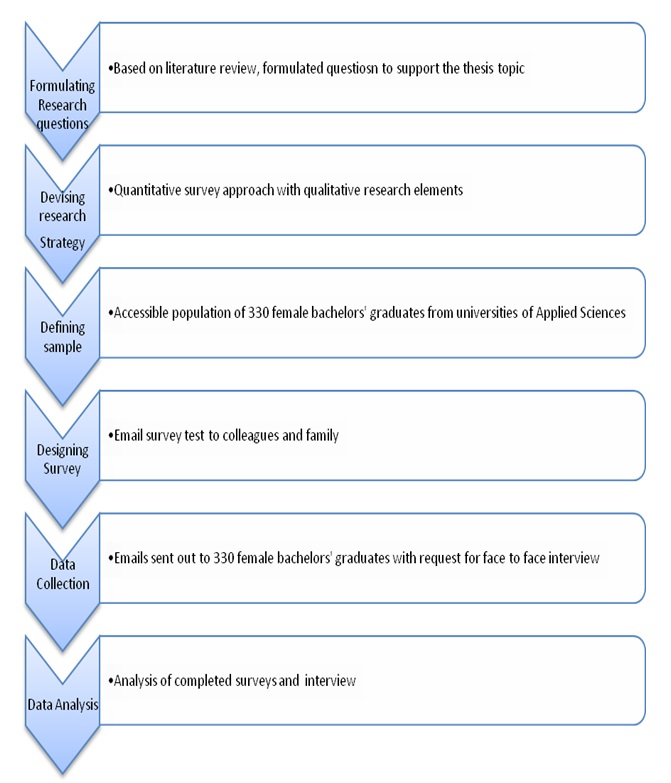

The objective of this section is to outline the research approach used and processes used in starting and conducting the survey up to analysis of the results.

Information from the different sources was based on data collected by others or from books written about the topic as well as the internet. In order to obtain further input, the survey of female bachelors’ graduates was conducted using the FHSchweiz alumni database. This was in the form of an online survey. Further input was collected from experts in the field i.e. University of Applied Sciences (HWZ) , interview with Silvia Karrer, a graduate form University of applied Sciences Zurich, as well as an interview with Brigitte Baumann, Founder and CEO of Go Beyond Ltd., and various correspondence.

Research questions

As already mentioned, the primary objective of this thesis is to contribute to the understanding of the career opportunities and challenges in management faced by female bachelors’ graduates of UAS in Switzerland. The preceding sections of this paper were designed to give an introduction on the theoretical contribution. The following sections will aim at answering the following questions:

- What are the career opportunities in management for female bachelors of business administration graduates from UAS?

- What are the career opportunities in management for female bachelors of business administration graduates from UAS?

Research Strategy

According to Yin49, there are three conditions which determine the use of a particular research strategy. First, the type of research question posed, second, the extent of control an investigator has over actual behavioural events and third, the degree of focus on contemporary as opposed to historical events. If the questions are formulated that start with “who, what, where, how many, and how much”, or if no actual control is required over events to be researched, and if the focus of the investigation lies on contemporary events, then the survey strategy is suggested. Given the nature of the research questions governing the present study, the corresponding lack of control, the questionnaire approach was chosen.

Population and sampling frame

As per definition, the term population, often also referred to as target population, comprises “entire groups of people, events, or things of interest that the researcher wishes to investigate”,50 “that shares a set of common traits”.51 The group chosen for this study logically follows objective and can be summarized as follows: Female bachelors’ graduates from universities of applied sciences in Switzerland.

Due to research constraints, such as difficulties with access to all female bachelors’ graduates, it was decided that members of the population should be accessible through online data service providers. The survey portal used for the survey was Zoomerang online. FHSchweiz provided their assistance by sending out the online survey through their email database which contains all female bachelors graduates registered under the FHAlumni.

Questionnaire design

A draft questionnaire was constructed based on surveys published online. For validity and reliability reasons, three design principles as suggested by Sekaran52 were considered when compiling the questionnaire. The three principles are: first, the principle of wording, second, the principle of measurement and third, the principle of general appearance. The first principle refers to the appropriateness of the contents of the questions, the level of linguistic sophistication and the form of sequencing. The second principle looks into how the answers to the questions can be interpreted and measured. The third principle is basically about the layout, length, instruction for completion of the survey as well as a proper introduction.

The draft questionnaire tested through discussions with the authors mentor and through other graduates from other universities (not UAS). A number of constructive suggestions for improvement of structure, content and wording were made and applied. The final version sent out contained twenty questions. Out of the twenty questions eleven were multiple choice or ones which could be answered by ticking the appropriate boxes (see appendix A).

To increase the response rate, a promise of confidentiality and anonymity to all respondents was given. A request to contact the author if respondent was available for a face-to-face interview was also included.

Data Collection

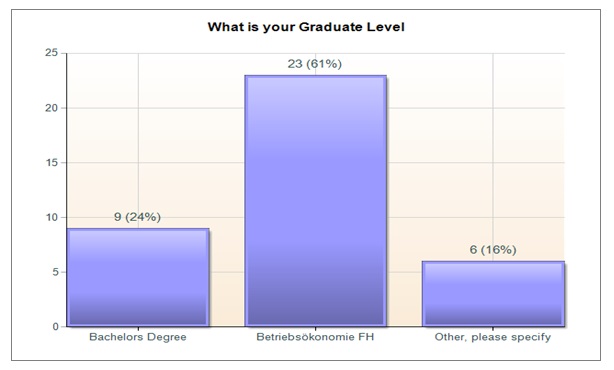

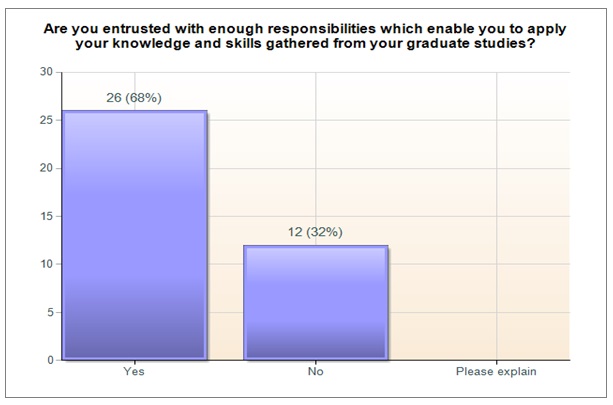

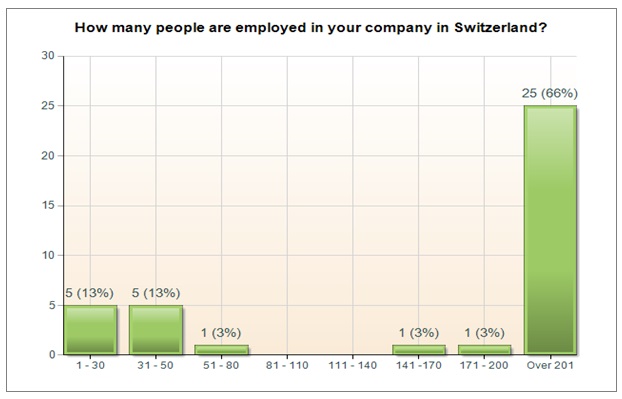

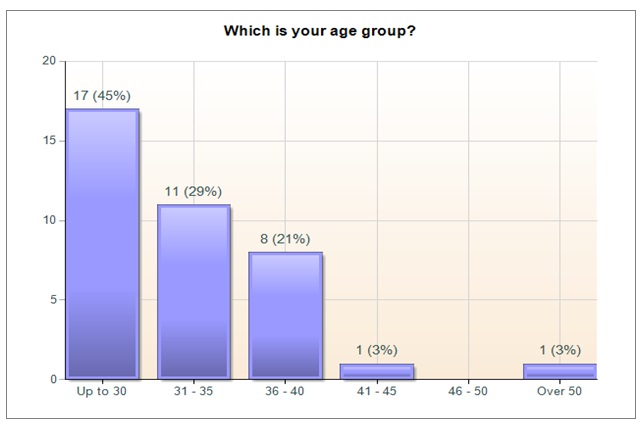

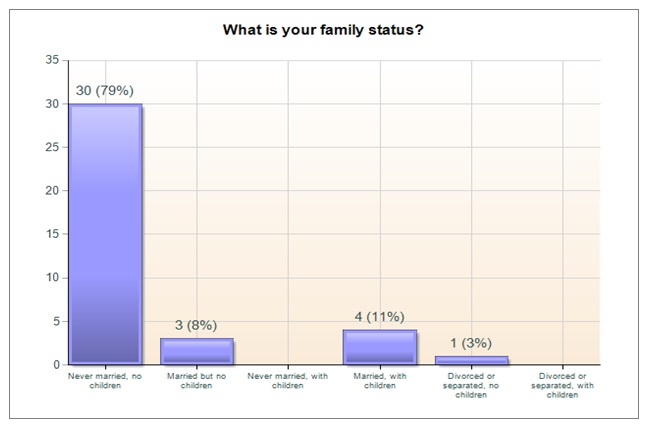

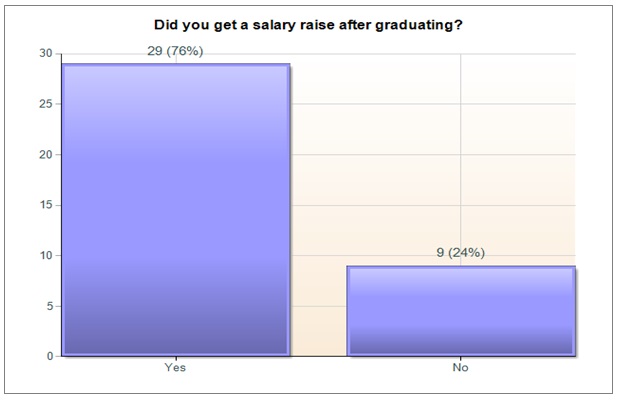

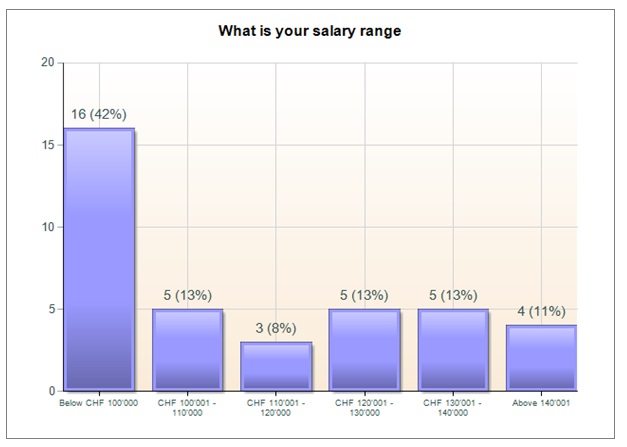

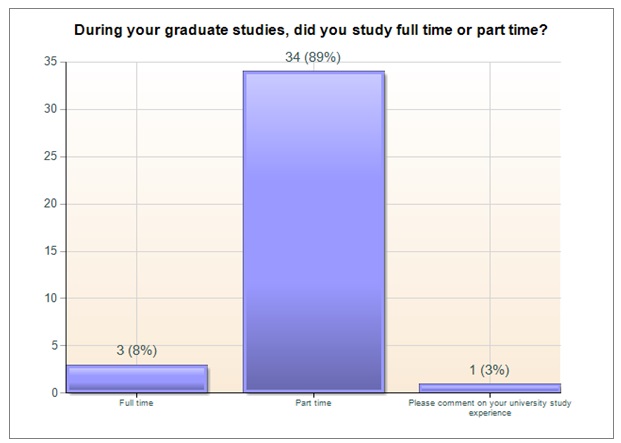

This was mainly through the online survey portal that provided a detailed report of all visits and all completed surveys. The survey was visited by a total of seventy eight and completed by thirty eight respondents. The online survey was running from 11.11.2009 through 11.01.2010.

Data Analysis

Influenced by the research questions, the initial descriptive analysis of the quantitative date produced figures giving an overview of the results (see figures 3 to 20 presented on the practical section of this paper). For the open-ended questions, the author summarized the feedback and presented it on the practical section of this paper. Further analysis was undertaken to compare the results to the contribution from secondary data.

Theoretical part

Graduation from institutes of higher education

Among the students obtaining the first qualification or degree in institutes of higher education (ISCED 5A) the proportion of women is higher than that of men in most northern and western European countries. In Sweden, Denmark and Finland between 58.5% and 63.1% of qualifications were obtained by women. In the neighboring countries of Italy and France women were in the majority with 58.1% and 56.9% respectively. Germany and Austria show a balanced scenario with the proportion of women sitting at 49.9% and 50.3% respectively. In Switzerland the share of women among graduates from such tertiary institutes remains still relatively low at 43.9%.

The trend in Switzerland is, however, worthy of note: in the four-year period from 2000/01 to 2003/04 the proportion of women graduating at higher education level rose slightly by 4 percentage points. After Belgium, Switzerland shows one of the highest increases in female graduates. At doctoral level, women are still under-represented in most countries. Exceptions to this are for example Finland and Italy where one finds a balanced share between men and women. The neighbouring countries of Germany, Austria and France fall in the middle range with the proportion of women falling between 39.0% and 41.7%. With a proportion of female doctoral students of only 36.9%, Switzerland belongs to the countries with the lowest rates in Europe. Trends between 2000/01 and 2003/4 show however, that women in Switzerland are catching up – their share has risen by 2.4 percentage points. We can observe an increase in the proportion of women engaged in doctoral level studies in the majority of northern and western European countries. Many countries, however, display a somewhat stronger increase. Only in Denmark has the proportion of women receded by 4 percentage points.53

Career Opportunities for Bachelor Graduates in the Coming Years

The Biotech Sector

While there are opportunities for recent Bachelor of Business Administration graduates in nearly every imaginable field in Switzerland, opportunities are especially plentiful in particular areas. These are the sectors that are the most financially healthy, including a number of fields that are relatively new to the country, such as the biotechnology industry.

The country is home to more than 150 biotech companies that collectively employ close to 15,000 employees. The country has the sixth largest biotech industrial sector in Europe (and the ninth largest in the world).54 Perhaps even more important than its current ranking, however, is the fact that the Swiss biotech sector is growing faster than that of any other European nation.55

There are a number of reasons for Swiss strength in this sector and thus of the numerous opportunities for recent graduates in this arena.

David Syz, the Swiss state secretary of economic affairs, attributed the Swiss dynamism to the existence of “advanced networking between research and industry,” “favorable tax conditions”56 and the availability of “more than 40 incubators and technology parks… Other factors have played a role, Zürcher says, such as the proximity of pharma giants Roche and Novartis, both in Basel, and the presence of universities with strong traditions in science and chemistry….“Because of these factors, the Swiss biotech sector”, Zürcher says, is mature relative to the rest of Europe.57

But the take-home lesson for other countries, concludes Zürcher, is “to let entrepreneurs be entrepreneurs right from the beginning.” Supporting nice but unworkable ideas with government funds, he says, only serves to prop up weaklings who will ultimately fail.”58

The biotech sector in Switzerland is relatively diverse – an important point for recent graduates to remember. Skills and preferences that may not fit the needs of one company may indeed be welcomed at another. While there are a number of pharmaceutical companies in the country, there are also more general life sciences research centres. This range ensures that there are jobs with wide differences in how much (and what type of) technical skills is needed and on the ways in which technical skill and business acumen may match up. This range of skills may allow women – who still major in engineering and other technical fields at lower rates than men – to find their place in high-tech firms.

The recent business graduate may also look to working situations outside of the typical for-profit company given the wealth of opportunities available in research labs and in education (both in terms of universities and trade schools). These jobs would almost always require additional schooling at some point for an individual with a bachelor’s degree in business. This should not, however, disqualify anyone who has just finished an undergraduate business degree. Those who have recently received a bachelor’s degree in business science will be attractive to firms in all fields.

This said, many of the jobs that a recent bachelor graduate may aspire to will require additional education at some point – if not initially – and so this is an aspect of the professional arc that each graduate must consider. Certainly, in Switzerland as in most places, additional education can add considerable opportunities for career growth. Moreover, some companies will make provisions for those with an undergraduate degree only to continue their education with support (sometimes including financial support) as the individual pursues a full-time job. Women especially should be encouraged to continue their education to overcome any prejudice that male managers have in hiring them.

The biotech sector is likely to continue to grow as it has done so even during the current recession and thus should be a serious consideration as a possible career destination for current and recent students. The Swiss Biotech Report this year summarized the continuing growth of this sector:

The Swiss biotech sector continued growing in 2008. “Although risk capital proved harder to come by than in the record year of 2007, the sector nonetheless managed to expand by achieving higher sales, licensing new products and starting up new companies”. 59

The latest figures suggest that the biotech sector remains a growth industry. For example, in 2008 Swiss biotech companies generated combined sales of more than CHF 8.7 billion, roughly 7% up on the previous year. Investments in research and development (R&D) by both private and listed companies also rose, totaling CHF 2,070 million (up from CHF 1,755 million in 2007), an increase of 18%.60

The trend towards more start-ups of new Swiss biotech companies continued in 2008. There are now 229 biotech companies based in Switzerland (as against 220 in 2007), including 159 biotech development companies and 70 biotech suppliers. The focus of Swiss biotech business is still on so-called “red” biotechnology, i.e., human and veterinary medicine.61

The biotech sector should be an attractive one for business graduates (as well as for others) because it seems likely to become increasingly important as each nation (and its firms) seek to find ways to address what will be the ever-escalating consequences of global warming.

While of course we should all be concerned for both personal and general humanistic reasons about what is happening to our shared environment and each work to do our part to limit the harmful effects of climate change, it is also important for the new college graduate to think in practical terms about his or her own professional future. Seeking work in the biotech sector may allow a graduate to do grow and do well at the same time. This may especially appeal to women graduates who tend to be more inclined to work for socially progressive causes.

The Medical Field

When one thinks about career possibilities in the medical field in Switzerland, one is most likely to think about work within the pharmaceutical industry since Swiss drug firms are so well established and so well known. However, there are other opportunities for business graduates within the medical field. Again, some of these jobs may require additional training or education as a person proceeds through his or her career, but a bachelor’s degree is in many cases it might seem something of a leap, these companies actually have their origins in the nation’s watch-making traditions of precision technology.62

“Switzerland has a history of advanced medical technologies and has continued to expand on this tradition through advancements in engineering, one of Switzerland’s core competencies. Due to its small size and lack of natural resources, the country built an economy around precision technology and quality. The combination of these precision technologies and the strength of Switzerland’s financial marketplace led to the creation of a unique framework for a worldwide, highly-competitive medical technology sector”.63

When seen in this light – as a combination of banking and engineering expertise – it is clear why the medical technology sector should have found such a successful place in Switzerland. Companies focus on developing new medical devices as well as on manufacturing existing devices in a range of sub-specialties, including “biomaterials, cardiovascular and dental implants and devices, diabetes devices, electro-medical and imaging equipment, orthopaedics, and respiratory equipment, surgical instruments and wound and care management.”64 Given the aging of the First World population, many of these medical devices will come into increasing demand in the decades ahead. Women are making important strides in all aspects of the medical field in Switzerland.

The following are among the leading medical device companies in Switzerland, each of which offers opportunities for recent business graduates:

- Synthes Inc., which develops and produces medical instruments, biomaterials for surgery, and technologies for the correction and regeneration of both skeleton and soft tissues. Their large marketing department offers opportunities for those with a business background. There are also opportunities in the company for employees with a range of research skills that are generally taught in business programs.65

- Allergan Inc., a company that produces and markets pharmaceuticals, also makes medical devices such as the lap band used in bariatric surgery and Botox, used for aesthetic considerations. Both of these products – the former because of the high risks that it involves, the latter because it is something not needed for health but rather used for cosmetic effect – require sophisticated marketing techniques and thus positions for well-trained business students. In addition to exploring markets for the company’s established products, business majors are needed to help Allergan explore new horizons for the company.66

- Edwards Lifesciences LLC., which manufacturer’s replacement heart valves as well as a number of devices to measure blood pressure and catheters for pulmonary-cardiac surgical and recovery procedures. These products are especially useful for an aging population, which means that the company is likely to be hiring an increasing number of workers in the years to come.67

- Invacare Europe Sarl., which produces and markets a range of both homecare and hospital supplies, including devices that improve mobility (such as scooters), those that allow patients to be moved (such as hoists and slings), devices that increase the comfort level of patients with limited mobility such as mattresses that reduce the possibilities of bedsores, and respiratory devices. The company’s marketing and research departments both need workers with a sound background in business. It also needs employees who can interface well with other factors in the healthcare business, such as hospitals and long-term care facilities for both the elderly and those recovering from illness or disease.68

Many female Bachelor of Business graduates may shy away from companies with such obviously technical focus and – as noted above – many of the positions in these firms require a significant amount of training and educational in technical fields. However, it is also true that these companies have need of business expertise. This is especially true the more international the company is, for a very large measure of selling products to other countries requires good fundamental business skills more than it requires technical expertise. (Or rather both are needed to complete successful sales.) Not only does an international company require a good line of products to sell, but it requires a staff with the training to understand the needs of a wide range of both business partners and the ultimate users of the company’s product. Women generally face few hurdles in entering the non-technical departments of such businesses. Thus, new graduates of undergraduate business programs should certainly consider looking for positions within the high-tech sector, including the two fields discussed above as well as others described below. With the centrality of high-tech fields to the Swiss economy, a jobseeker who dismisses outright high-tech jobs because she or he does not already have substantial technical training will be severely limiting her or himself unnecessarily.

Nanotechnology

As suggested above, an important area of growth for business opportunities for future female bachelors’ graduates is the field of nanotechnology. Nanotechnology is the sector of engineering, research, and business that focuses on objects that are smaller than 100 nanometers and often involves working with individual molecules. Such technologies are used in a range of fields.

“In successfully developing new applications, products and manufacturing techniques using micro-nanotechnologies and precision engineering, Switzerland is considered at the top in this field. Additionally, nanotechnologies represent an enormous source of technological advancement for numerous industry sectors, including medical technology, biotechnology, chemistry, environmental protection, semiconductors, and high precision optics and information and communication technologies”.69

As is true of the medical firms described above, nano-technology firms need a range of workers, including those with a business background. Indeed, understanding basic business models is an absolute essential in terms of exploiting nanotechnologies to their greatest degree. There are many inventors and engineers who can create wonderful new gadgets; however, these will not be any good to a business (or to the customers who may want the products) unless these technologies can be folded into overall business goals.

Among the Swiss nano-tech companies that are likely to welcome new graduates are the following:

- eXtremeTAG, (a subsidiary of Elecsys Corporation)70, which produces RFID (radio frequency identification) tags. There is an important amount of engineering skill that goes into such tags, but at least as important – and arguably even more important – is an understanding of business product cycles. eXtremeTAG produces RFIDs that allow companies to track “assets” (i.e. whatever it is that the company makes) through the entire supply chain, to “monitor utilization” throughout the length of that chain, to “track maintenance, calibration, repair, and testing in the field”, to provide real-time verification, and to secure all of this information.71 The RFID tags themselves are the products of engineers: They cannot be designed or manufactured by someone with a bachelor’s degree in business that has no other training. However, the kind of worker who can explain in precise and compelling terms how an RIFD chip can be used to supplement and improve the business cycle of any given company will be one who is well grounded in business development planning.

- Rüeger SA, which produces a range of thermostats and thermometers that rely on nano-technology. These temperature-sensing devices can be used in a range of larger machines and so the company has need of employees who can research the need of other companies for Rueger’s devices.72

- The Dixi Group, which produces a number of different nano-tech devices for use in medical treatment, including electrodes to be placed into brain tissue.73

- Mimotec SA, which – in a most Swiss way – creates sophisticated clockworks. But – in a most 21st-century Swiss way – has extended this technology into other areas such as medicine and aerospace technology74

Any company that distributes its products to a number of different fields as Mimotec does has need for workers who are skilled in fundamental business tasks such as coordinating the demands of different divisions within the company as well as with vendors in very different business realms.

Increasingly important

The stereotypical idea of progress tends to be “the bigger, the better”. But in the past decade nanotechnology – the art and science of the nearly impossibly small – has become increasingly important as the potential uses for very small tools have become increasingly apparent. Between fifteen and twenty new nanotechnological products are released into the marketplace each week.75 This brave new small world offers both traditional barriers and novel opportunities to women entering the workforce – as well as women who may be marking a career change.

The traditional barriers are obvious: Women remain under-represented in science and technology as professional fields for a number of reasons, including a lack of confidence on the part of women that they can compete in these fields, lack of preparation in school for such fields by girls (who are often discouraged from taking math and science courses), and general lack of social support for women entering these fields. This lack of support can extend to those who do the hiring at high-tech firms.76 There are a number of feedback loops in this system in which women are discouraged from competing in high-tech fields, and this discouragement on all levels reinforces women’s hesitancy to enter into high-tech fields – or to push their way through initial resistance that they may meet.

It is important to note here that while the above might sound as a condemnation of women for their hesitancy it is anything but. While Switzerland is free of formal legal and institutional barriers to women’s entering any field that they like, there are still significant cultural, social, and psychological barriers to their entering high-tech fields. It is only natural for anyone considering what career path to take to enter into a field in which they will feel welcome. This has not been the case for women in technological and scientific fields over the past several decades in fields such as pharmacological research.

However, even as these factors work against women entering and succeeding in high-tech realms, there is a significant counterforce in some technological fields that serves to help women: Any new professional field has fewer of the old structural restraints and barriers than do established fields. The newer the field, the fewer established institutional barriers exist to women. This latter fact makes the field of nanotechnology relatively welcoming to women – among the most welcoming of the newer technologies that are becoming increasingly important to the Swiss economy.77

This does not mean that there are no barriers to women’s entering into the field of nanotechnology in Switzerland or anywhere else given that it is a part of the technological business sector. However, there are established professionals in the field who are trying to make it easier for the next generation of women, in part because these veteran professionals recognize that nanotechnology – with its huge future potential – is an excellent entrance point for women into a scientific field. For example, there is a new multi-nation group – WomenInNano – that has formed to encourage women to enter the field by linking women entering the field with those who are established within it. This group may have collateral benefits for women in Switzerland or it may expand into Switzerland – or a native Swiss group may rise up to fulfil the same functions.

Dr Annett Gebert from the Leibniz-Institute for solid state and materials research in Dresden is the coordinator for the project, and talked to CORDIS news and said the she was very involved in the scientific community where she felt that the industry was dominated by males at all levels. They also felt that younger girls were not considered for the natural career path and her institute would look into that matter and do something about it.78

The fact that women who already in the field of nanotechnology are willing to reach out to help other women entering the field – even if such actions are still taking place in Switzerland on an informal basis – should be an important consideration for women who wish to enter this subfield. Nanotechnology offers a way into the world of high-tech jobs (which in turn offer substantial intellectual as well as financial advantages for women) with at least a lower entrance fee than is generally charged to women attempting to enter into high-tech fields.

But while it is generally true that nanotechnology is more welcoming to women than more-established high-tech fields, the field is not uniformly gender-neutral or welcome to women. There are different subfields of nanotechnology because the field, while still extremely new, is well-enough established (and scientifically, technologically, and socially complicated) to have begun to give birth to internal divisions that require different types of workers. Some of these subfields are more welcoming to women in part at least because they offer jobs that require interdisciplinary approaches that women may find attractive.79

Engineering and Social Engineering

One of the most important new subfields in nanotechnology that may attract women in (and into) the field (as well as, of course, men) is that of nanotoxicology, which is most generally the exploration of the ways in which substances composed of very small particles can have toxic effects on humans and other animals. This field may be especially attractive for many women – although in saying this I am aware of the fact that I am trending a fine line between talking about new careers for women and traditional gender views of what is “appropriate” work for women – because it focuses on what we might call (with apologies for using a cliché) the human condition. Nanotoxicology is a highly integrative field that allows for workers to combine the most advanced science and technology with a consideration for some of the most sophisticated and compelling medical questions.

Some researchers have found that one of the reasons that women do not seek out nanotechnology as a career (in addition to the reasons that I have already cited, such as lack of role models for young women in science and discouragement by educators who steer girls into non-science classes) is that it seems “soulless”.80 This assessment of the field of nanotechnology by young workers considering pursuing a career in this field probably arises at least on large part as a result of the fact that the majority of the day-to-day work done in nanotechnology firms is technological rather than scientific in nature. There is nothing, of course, wrong in technological work. However, it provides relatively little in terms of intellectual challenge (as opposed to science) or social connectedness.81

As noted above, this paper does not presume that all women are interested in fields that offer the possibility of furthering social concerns – or that many men are not so inclined. However, a number of researchers into the field, especially those that examine new trends in hiring, have found that women entering the field are often attracted to the corners of the field in which science, technology, and social concerns intersect.82 One of the most important of these areas is that of nanotoxicology. While nanotechnology can be seen as existing at the conjunction of science and technology, nanotoxicology can be seen as occupying an even more complicated connection – that created by environmental concerns, science, technology, and the role of all of these within democratic forms of governance.

Nanotoxicology

Global warming has taught us two important lessons. The first of these is the particular atmospheric chemical consequences of the Industrial Revolution. The second, more general lesson is that every technological advance must be paid for. In the world of technology perhaps more than any other area of human endeavour there is never a free lunch. This is no less true in the field of nanotechnology than in any other technological field. There are an increasing number of jobs in this field, and they offer to job-seekers a fascinating amalgam of science, technology, and social questions.

To understand the field of nanotoxicology, one must understand something about the ways in which nanoparticles – particles that have a diameter of less than 100 nm – are produced. There are clear connections between the ways in which particles are produced and the potential harm that they pose to humans (as well as other life forms). There are three basic kinds of nanoparticles that nanotoxicologists will come across. There are naturally occurring nanoparticles – such as those that occur in the wake of volcanic eruptions. There are nanoparticles that occur as the result of combustion, some of which are natural (such as those that occur during a forest fire). Still others are the result of the new technologies

There are two distinct reasons why nanotoxicology is an appealing field now, especially for those who are interested in examining the intersection of technological and social change. The first is that some nanotoxicological effects are the direct result of new nanotechnologies: There is a strong ethical argument that can be made that as humans develop new technologies we must also – and as simultaneously as possible – develop strategies to counter any detrimental effects of the new technologies. (This is a corollary of the second lesson of global warming.) This could also be seen as a sort of corollary of the Hippocratic Oath: If at first you can do no harm than as quickly as possible move to fix the harm that we as humans have caused.83

“Nanoparticles are supposed to have different properties than the larger particles which a result of their size”.84

The following diagram suggests some of the complicated ways in which nanoparticles can affect human health and some of the ways in which nanotoxicologists can begin to derive strategies to combat the potential harmful effects of nanoparticles.

If we look only at the element of “risk characterization”, for example, we can see that there are both technological and social issues at work: The effectiveness of control (for example) of the potential dangers of nanotoxicology arises from both technological as well as human agents. Swiss scientists have been active in this push to create mechanisms – both technological and cultural – to limit any possible damage from human-produced nanoparticles. They have joined with researchers from across Europe and North America to create collaborative networks to investigate – and, when necessary, remediate – the consequences of nanotechnology.

“Nanotechnology provides the opportunity for enabling new products that could meet a wide range of societal needs, but concerns over potential environmental, health and safety impacts of these materials may limit their adoption. Multiple organizations, including the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Nanotechnology Conference for Communication and Cooperation (INC), have highlighted the importance of international collaboration to accelerate understanding of nanotechnology implications for society”.86

The field of nanotoxicology is so new that it is very much still in the process of being defined and anyone entering it in the next several years will have the chance to help determine in what directions the field will go. Not only are there very few answers yet in the field of nanotoxicology, but the questions also themselves have still barely been asked, as the following overview of the field suggests:

The potential exposure routes of a nanoparticle vary during its lifecycle. “During the manufacture of a product, free engineered nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes might be present in the air during production or might be released into the environment with waste materials or during production accidents. Product use could lead to exposure to engineered nanoparticles through the skin (cosmetic products), ingestion (food ingredients or packaging) or injection (medical procedures). After regular use, recycling or degradation of products might release engineered nanoparticles into the environment and lead to high concentrations in water, air or soil, which in turn could lead to exposure through skin, inhalation or ingestion”.87

There is a wide range of possible jobs suggested in the description above: Nanoparticles are finding their ways into more and more parts of our world, and this has happened with very little oversight.

Strong ethical element

Nanotechnology has crept into so many corners of our lives that most of us are not even aware of the ramifications of these technologies. Fortunately, a number of firms are concerned that work being done at the edges of the known technological universe is being done with a strong ethical element so that humanity may benefit from nanotechnology rather than suffer from it.

There is significant potential for harm to crop up in nearly impossible to imagine contexts produced by nanotechnology. For example, nanoparticles of silver (or nano silver) are now added to everything from socks to bandages because of its ability to reduce odour as well as its antibacterial properties. This fact might seem to be relatively innocuous, but scientists have found that these nanoparticles of silver can be washed out of items such as socks and into the water supply, where they may become toxic. Researchers have found that “silver nanoparticles can travel through the wastewater treatment system and can reach the aquatics, where these nanoparticles can have adverse effect on aquatic organisms living in the water.”88

The researchers in the above study concluded the following:

People at large are not aware about the ingredients present in the consumer products they buy. Researchers further suggest that unlike food labelling, clothes containing silver nanomaterials should also be labelled so that the users can identify the ingredients present in the product they are buying and their possible threat to environment and humans.89

The above description provides, in its description of a small problem, a suggestion of the entire realm of possible nanotechnological research and work: How can we use nanoparticles to make our world a better place while ensuring – through science, technology, and social change – that this technology is not life-threatening in its consequences. Women can – and should – be at the centre of this effort.

Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship has never been more important than it is today. Global Ventures (GV) partners have explained in their website that the engines of growth and job creation in the 21st century are innovation and entrepreneurship which can aid building sustainable economic development, creating jobs, generating renewed economic growth and advancing human welfare.90

Definitions of Entrepreneurship

Global Ventures have put the definitions of Entrepreneurship as follows; “There are varying views and definitions of entrepreneurship around the world and other words often used as substitutes including enterprise, innovation, small business, growth companies, etc. To fully capture and understand the entrepreneurship phenomenon, it is important to take a broad and inclusive view, otherwise important components and trends in the rapidly growing entrepreneurship movement will be overlooked”.91

Education

Education plays an essential role in shaping attitudes, skills and culture – from the primary level up and is essential for developing the human capital necessary for the society of the future. The Junior Achievement Young Enterprise had this to say in their European Summit held in 2006 titled entrepreneurship and education, “The earlier and more widespread the exposure to entrepreneurship and innovation, the more likely it is that students will consider becoming entrepreneurs in the future”.92

Global Ventures partners are of the opinion that schools and universities can and should play a key role in promoting entrepreneurship and innovation by helping students learn how to start, grow and maintain enterprises. While the skills and attitudes can take many forms during an individual’s career, they create a range of long-term benefits to society and the economy. They go on to say that by adopting to new models, frameworks and paradigms, educational institutions need to adopt 21st century methods and tools to develop the appropriate learning environment for encouraging creativity, innovation and the ability to “think out of the box” to solve problems. 93

It is not enough to add entrepreneurship on the perimeter – it needs to be central to the way educational institutions operate. By adopting to new models, frameworks and paradigms, educational institutions need to adopt 21st century methods and tools to develop the appropriate learning environment for encouraging creativity, innovation and the ability to “think out of the box” to solve problems. This has led to the role of educational institutions within the entrepreneurial ecosystem to change. The educational institutions will therefore need to work with the public and private sectors as well as other stakeholders to develop entrepreneurial societies more effectively. To achieve this goal, academic collaboration with businesses will need to be established and outreach should be encouraged and supported. Financial support, expertise, mentoring can be given by companies and entrepreneurs by having a close cooperation between academia and business. 94

The OECD in their book on Entrepreneurship and higher education state that, “Stimulating innovative and growth-oriented entrepreneurship is a key economic and societal challenge to which universities and colleges have much to contribute”.95

Global Entrepreneurial women Challenge Career Concepts

The rising numbers of female entrepreneurs worldwide clearly suggest the business ownership has emerged as an important career alternative for women. Moreover, the patterns women are following in the establishment of their businesses suggest they are pursuing careers without boundaries.

The recent rise in female entrepreneurship has been preceded by more than three decades of increased female participation in the labor force. 96

The study of the careers of women who seek managerial –corporate and entrepreneurial challenges, the boundary less careers, begins with the work of Edgar Schein. In mid 1970s, Schein proposed that, for most people, careers were constructed from a self-perception of their motives and needs as these evolved through life. As a person gained occupational and life experience, said Schein, the evolving self-perception functioned both as a career guide and a stabilizing force, an anchor of values and motives that a person would not abandon when forced to make an important choice. The early research Schein conducted indicated that most people’s career anchors revolved around the five basic categories: autonomy/independence, security/stability; technical-functional competence; general managerial competence, and entrepreneurial creativity. 97

Entrepreneurship in Switzerland

On the international entrepreneurship website, an article referring to the total Swiss entrepreneurial activity gave the following information “Entrepreneurial forces are mixed in Switzerland. The country has created an environment that makes starting a business or investing in one relatively easy. There are some experts who argue that much of Switzerland’s innovation and entrepreneurship comes from the outside. Internally, innovation is not taught and there is a fair level of risk aversion. Entrepreneurship as a field of study is, however, gaining acceptance and momentum”.98 This quotation is supported by other networks as shown below.

Women entrepreneurship in Switzerland

Swiss women have built up networks such as, BPW (Swiss federation of business & professional women), WIN (women innovation network) and NEFU (network of start-ups builder).99

The most recent organization for Swiss female entrepreneurs is the club for women entrepreneurs (CWE). It is a non-profit, non-governmental organization founded in Geneva, Switzerland, on 3rd September 2002, to promote and assist in the creation and development of viable and sustainable women’s enterprises in Switzerland and abroad.

CWE defines its vision as follows:

- To unite women active in managerial positions in Switzerland and abroad for professional networking and mentoring which may assist them in the creation and development of their enterprises;

- To provide opportunities for continuous learning through luncheon presentations, seminars, company visits, business trips and special events with a highly professional content;

- To grant material and other aid to women in areas where conditions of gender equality, economic and legal frameworks are less developed than in Switzerland.100